Robert Langer recalled humming along to the Rolling Stones hit “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” in his MIT apartment, anxiously awaiting the results of his PhD qualifying exam. “It was a very hard test,” he said. “I really thought I had failed, but in the end the Faculty Review Board must have been kind because they passed me.”

Since graduating from MIT in 1974 with a ScD in chemical engineering, Langer has gone on to serve as an Institute Professor at MIT, the highest distinction awarded to an MIT faculty member; preside over the largest academic biomedical engineering lab in the world; conduct research in medicine and biotechnology that has improved the lives of over 2 billion people, become the most cited engineer in history; and garner countless awards and accolades for his work.

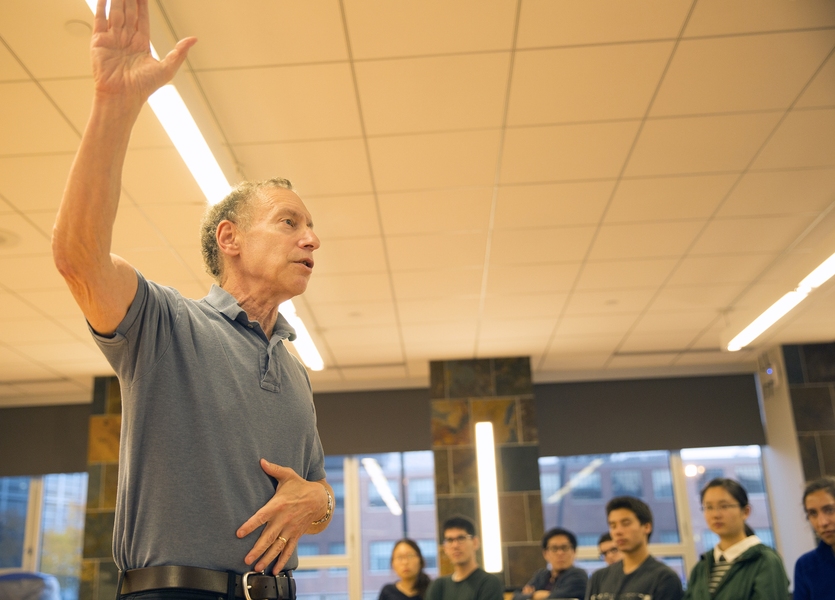

Though it may seem easy to imagine Langer breezing through graduate school with a clear vision of his future accomplishments, he says that uncertainty and failure were very much a part of his college life. Speaking to a group of 50 graduate students at Ashdown House on Oct. 18, Langer discussed his experiences as part of the “Failures in Graduate School” monthly seminar series. Organized by PhD students Stephanie Chen, Malvika Verma, and Seamus Bann, and sponsored by the MindHandHeart Initiative, the series provides an opportunity for students to connect with MIT faculty on a personal level outside of the classroom.

“We wanted to create a venue to learn about MIT professors’ lives when they were graduate students like us,” Verma said. “For first-year PhDs who are struggling to secure a position in a lab, or adjusting to life in a new country, or feeling overwhelmed by their demanding course load, it’s helpful to hear that failure and self-doubt are normal and happen to everyone.”

“Professor Langer was a great person to kick off the series,” Verma continued. “Despite his vast accomplishments, he faced a lot of rejection early on in his career and is open to discussing these experiences. Being a graduate student at MIT was a part of his life that doesn’t appear in the news, but it helped make him who he is today.”

Making the biggest difference

During his presentation, Langer offered a personal account of his four years as an MIT student, recounting everything from spending late nights in the lab to the disappointments and hard decisions that led him to pursue a career in the medical field.

“My first year was tough,” Langer began. “I took the required chemical engineering courses — thermodynamics, heat and mass transfer, and industrial chemistry — and they were all really hard for me. The class average for one of my first exams was 20 out of 100, which included the five points everyone received for spelling their name correctly. It was discouraging at times, but I worked really hard and I got through it.”

Having conducted little research as an undergraduate, Langer struggled to find his place in the laboratory. “I felt like I was a disaster,” he said of having to seek help from postdocs and fellow students to correctly use the equipment and follow standard lab procedures. He also felt a waning interest in his thesis on the enzymatic regeneration of ATP, unable to imagine a practical application for his research.

Though his time in the lab often left him lonely and frustrated, Langer found a rewarding outlet volunteering as a tutor in Roxbury and Cambridge. “At the time, Cambridge had the highest high school dropout rate of any city its size in the U.S.,” said Langer. “It had Harvard and MIT, but it also had several large housing projects and a lot of poverty. I tutored kids from these neighborhoods in math and science, and I was good at it. I enjoyed working with students and seeing them progress — I still do.”

In Langer’s second year at MIT, he was approached by a group of educators to develop a science and math curriculum for a new school in Harvard Square. “The school was very liberal,” Langer said. “There were no required classes and as a result only five out of 40 students signed up for math the first year. It became a real challenge for me to figure out how to make math and science fun for these kids. I incorporated a lot of games and practical problems, and by the second year 45 out of 50 students enrolled in math and almost everyone took chemistry. I was really proud of that.”

Although Langer knew he had a knack for teaching, he recognized the limited influence he would have working as a high school educator. “There was a part of me that wanted something more,” he said. “If I became a high school teacher I would help some people, but it didn’t seem like the way I could make the biggest difference.”

Charting an “unusual” course

During his fourth year at MIT, as many of his classmates were heading off to lucrative jobs in the oil industry amid the 1970s energy crisis, Langer was unsure of his next steps. “Oil companies would recruit on campus and I ended up getting 20 offers — four from Exxon alone. But I wasn’t excited about it. I remember one of the Exxon guys telling me that if I could only increase the yield by 0.1 percent how great that would be — it would be worth billions. I remember thinking to myself, ‘I just don’t want to do this,’ which was a very difficult realization because then I had to consider what was I going to do.”

Langer saw an advertisement for a chemistry professor position at City College of New York that piqued his interest in curriculum development, and he wrote a letter applying for the job. He never heard back. He applied to 40 similar positions and was flatly rejected from each, learning that even though he had done well at MIT, he didn’t have the qualifications to become a chemistry professor.

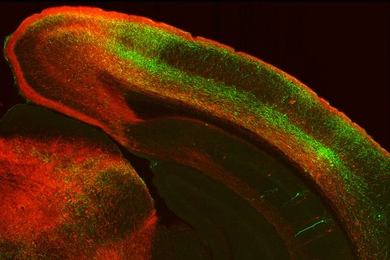

A classmate told him about a surgeon at Boston Children’s Hospital named Judah Folkman who was known to hire “unusual people.” Langer met with Folkman and was fascinated by his research on halting the spread of cancerous tumors by blocking the growth of blood vessels. “Even though it was the lowest paying job I could have had; even though I had no background in medicine; and even though I was the only engineer in the entire hospital, I took that job and it changed my life.“

“I ended up learning a tremendous amount about biology and medicine from Dr. Folkman and my colleagues at Children’s Hospital. Because I knew something about engineering and something about medicine, I was able to put those concepts together to come up with new ideas, and I think that’s why I’m an MIT professor today.”

Following his presentation, Langer participated in a Q&A session, fielding questions on choosing a thesis topic, selecting an advisor, and deciding on a career path. When asked what the biggest piece of advice he would give to a student, Langer offered: “When you pick a career, don’t do it because of money or any reason other than you feel in your heart that you’ll love it and it could have an impact on the world.”

For more information on the “Failures in Graduate School” seminar series and upcoming events, visit the MindHandHeart website or contact Malvika Verma at mverma@mit.edu.

To learn more about Robert Langer’s professional journey, watch his presentation from the “Faculty Talks: Getting from Here to There” series on Nov. 30, 2015. Other talks from the series are available here.