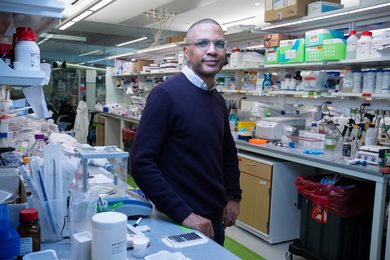

Anthropologists often work best with one foot inside a society and one foot outside it: They are steeped in a culture, but detached enough to analyze it. For Manduhai Buyandelger, this vantage point is part of life itself. She is a Mongolian anthropologist at MIT, whose work illuminates her home society and very much derives from her own insider-outsider relationship to it.

Consider: In a nation whose self-image glorifies nomads on the rural steppes, Buyandelger is a city dweller raised in downtown Ulan Bator, the capital. Growing up in Mongolia during the Cold War, she attended Russian schools, giving her an uncommon perspective on both her own nation and the Soviet regime that was controlling it. Indeed, studying politics, propaganda, and the country’s shift to a post-Soviet society has been essential to her research. And for all of Buyandelger’s deep roots in Mongolia, she has lived in the U.S. for years, returning home periodically for intensive research.

“All these things gave me ways of thinking about diversity and cultural differences,” Buyandelger says. “There were hidden parts of life I found intriguing, such as religion, which people practiced every day in secret. I lived with those contradictions from very early on.”

Her work reflects this. Buyandelger’s first book, “Tragic Spirits,” about the surprising return of shamanism to post-Soviet Mongolia, concluded the return of older religious practices was a way for Mongolians to re-establish their national identity. Her current book project examines women in Mongolian politics, as they establish themselves in the rapidly changing, free-market culture that has altered their social roles.

Or, as Buyandelger puts it, she tries to make sense of the “change, discord, propaganda, and inconsistencies in everyday life,” having experienced plenty of these things herself.

“Socialism collapsed, right in front of my eyes”

Growing up in Ulan Bator, Buyandelger found herself attending rigorous Russian schools that were built mainly for the children of Soviet expats; the U.S.S.R. controlled Mongolia as a satellite country during the Cold War.

“I think that going to a Russian school gave me some dual background and some way of comparing things, and being able to associate myself with not only one culture, but multiple cultures,” Buyandelger recounts.

In the meantime, she also witnessed some of the splits within Mongolian culture. For instance, her mother’s parents recoiled from living in the family’s apartment in the middle of Ulan Bator. Instead, they remained in the outskirts of the city, a place where “they had to bring in their own water and firewood. … They didn’t care about about modern amenities. For them it was important to have access to the outdoors and have their own little plot of land.” As Buyandelger noticed, some Mongolians retained private traditions and older values even given an opportunity for change.

By the time she started college, Buyandelger wanted to become a fiction writer. But then events overtook things: The Soviet Union and its whole socialist system starting breaking up, and she wanted to analyze it.

“Right when I entered college, in 1989, socialism collapsed, right in front of my eyes,” Buyandelger says. “It was the time of the democratic movement, the demonstrations. My walk from my home to the university went through the main square, and that’s where everything was taking place. … I really wanted to write about those transformations that took place: What did they mean for a country that was so consistently and neatly packaged as socialist, as it burst into complete chaos and embraced change so eagerly, and tried to build everything anew?”

Buyandelger’s career path took shape when she received a Fulbright scholarship to study in the U.S. This allowed her to start graduate school at Harvard University, where scholars such as Nicola di Cosmo and Michael Herzfeld took note of her remarkable linguistic range — Buyandelger could then do research in traditional and contemporary Mongolian, Russian, English, and ancient Tibetan, and read French — and encouraged her to continue.

After receiving her PhD from Harvard in 2004, Buyandelger spent three years in the Harvard Society of Fellows and then joined the MIT faculty in 2008. She is the Class of 1956 Career Development Professor and was awarded tenure in 2016.

“There’s no easy solution”

Both of Buyandelger’s books lie at the junction of culture and the market. In “Tragic Spirits,” which she researched mostly in remote rural areas, the end of communism led to a new breed of shamans — storefront entrepreneurs offering their services as seers. This helped them make money and survive in the new economy, and in the process, helped people re-assert a form of Mongolian identity after the Soviets shuttered religious expression.

Her ongoing book project, titled “A Thousand Steps to Parliament: Elections, Women’s Participation, and Gendered Transformation in Postsocialist Mongolia,” similarly finds unanticipated developments after the end of socialism. The book is about female parliamentary candidates running for office in increasingly commercialized election campaigns. In this case, while Mongolians enjoy far more freedom than they once had, commercial culture has also changed Mongolia’s gender dynamics, Buyandelger thinks, in a way that affects politics.

“During socialism, the state purposefully, with the help of women’s organizations, propagated images of working women and women heroes and professionals,” Buyandleger observes. “So there were not sexualized images of women. They were presented as model citizens, in medicine or as teachers, or women workers laying bricks. That disappeared. With the commercialization [of the market economy], the images of women switched, from idealized workers to [those of] beauty pageants, trophy wives, entertainment. That’s the transformation of state-sanctioned gender ideas to market-dominated ones.”

Women face multiple new challenges as a result, from finding political funding in a campaign-intensive culture, to presenting themselves in ways that are professional yet nonthreatening, Buyandelger believes.

“The double bind is they have to meet the requirements of [a] sexism that allocates feminine and masculine features in a very distinct way,” Buyandelger says. “They have to be feminine enough to be accepted by gender norms … but if they are [too] feminine, that prescribes them into a lower stratum.” As she sees it, some women in politics have made strides by presenting themselves as being professionally successful in ways that register well with voters, but others have struggled. Many female candidates, in Buyandelger’s view, present themselves as being “intellectful” — a word taken from the Mongolian term “oyunlag,” which translates as “with intellect.”

So as with religion, in politics there are problematic social fractures and tensions that have developed, almost inevitably, as an old culture has collided with radical political and economic changes. But these struggles are exactly what makes Buyandelger want to study her home country in unique detail.

“That’s what the country is struggling with, and there’s no easy solution,” Buyandelger says — partly as an insider, partly as an outsider, and always as an observer.