Believe it or not, there was a time when MIT’s newest Rhodes Scholar, Stephanie Lin, didn’t excel academically.

“In fourth grade, I was a pretty bad student,” she says. “Sort of distractible, not very motivated.

“I guess I got over that,” Lin laughs. The senior biology major, who was among 32 American students to win the Rhodes in November, is poised to pursue a career in medicine after four years at MIT packed with classes, research and extracurricular activities.

Growing up, Lin says, she leaned more toward the humanities than the sciences, considering myriad professions — librarian, lawyer, poet — throughout middle and high school. It wasn’t until a summer research experience at Michigan State University before her senior year of high school that Lin found herself drawn to the puzzles of the natural world, and the dynamic environment of the research lab.

Arriving at MIT as a freshman, Lin thought she wanted to study chemistry, but quickly switched paths again, to biology. “I took 7.012 [MIT’s introductory biology course] with Eric Lander and Rob Weinberg,” she says. “I haven’t really looked back since.”

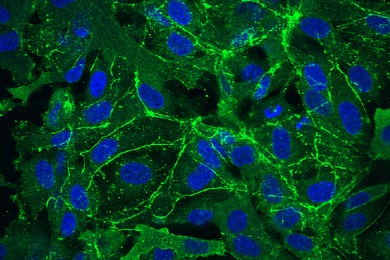

Lin recently completed her senior thesis in the lab of Jeroen Saeij, an assistant professor of biology, where she investigated Toxoplasma gondii, an infectious parasite that serves as a model for malaria because of its similarities to the parasite behind the mosquito-borne disease. Lin’s project looked at a specific protein found within Toxoplasma, and how that protein affects which genes are turned on and off in host cells invaded by the parasite.

With the help of a team in Saeij’s lab, Lin created two versions of the parasite — one with the protein in question, the other without — and infected host cells with them, comparing how the cells’ behavior differed in the two versions.

“We found that [the presence of this protein] was potentially changing the way that host cells sense nutrients,” Lin says. “Now the hypothesis, or at least the suspicion, is that it allows a parasite to usurp more nutrients from the host cell,” which in turn allows the parasite to grow and replicate faster.

In addition to her lab-based research, Lin has a passion for putting biology into practice: She has undertaken two service trips through MIT’s Global Poverty Initiative, both to a small Mexican village where farmers were struggling to increase their crop yields. While lab work is often concerned with pioneering high-tech methods, Lin says her experience in Mexico showed her that in real-world settings, great progress can be made simply by connecting people with tried-and-true resources. In the villagers’ case, the solution involved greenhouses, fertilizers and crop rotation — relatively simple strategies, but ones previously unfamiliar to these farmers.

“We have so much more access to information just because we’re students living in a more developed place,” Lin says. “We can Google anything that we want to find; we can look for people in our area who are experts in almost any field. When you’re in a rural community you just don’t have that. There’s no Internet, and there’s very little exchange of information between the city and the countryside.”

Lin’s experiences in Mexico gave her an appreciation for the challenges facing those in developing countries — but in fact, she has seen similar issues closer to home. Since her freshman year at the Institute, she has volunteered with Health Leads Boston, an organization that helps low-income patients access the social services they need, such as food stamps, subsidized housing and utility assistance.

Working at Health Leads “made me realize how many resources there are in Boston, but also how difficult they can be to access,” Lin says, adding that her most challenging case involved a pregnant patient with rheumatoid arthritis who lived two hours from Boston Medical Center and lacked personal transportation. Lin says she would often “run out of lecture and give [the patient] a call,” to make sure that the prearranged taxi had arrived on time.

“Sometimes — often, actually — it’s just about helping someone get the simple things they need,” Lin says.

Looking forward, Lin is drawn to the study of infectious diseases, which she sees as an ideal combination of biology, research and social issues. She is considering applying her Rhodes scholarship toward a master’s degree in medical anthropology at Oxford University in the U.K. before attending medical school, focusing on what she calls the “humanistic aspects of medicine,” such as the best way to get patients to adhere to a treatment plan and factors that lead to the spread of disease.

Whichever direction Lin’s career takes her, one thing’s for sure: No longer can anyone accuse her of being unmotivated.

“In fourth grade, I was a pretty bad student,” she says. “Sort of distractible, not very motivated.

“I guess I got over that,” Lin laughs. The senior biology major, who was among 32 American students to win the Rhodes in November, is poised to pursue a career in medicine after four years at MIT packed with classes, research and extracurricular activities.

Growing up, Lin says, she leaned more toward the humanities than the sciences, considering myriad professions — librarian, lawyer, poet — throughout middle and high school. It wasn’t until a summer research experience at Michigan State University before her senior year of high school that Lin found herself drawn to the puzzles of the natural world, and the dynamic environment of the research lab.

Arriving at MIT as a freshman, Lin thought she wanted to study chemistry, but quickly switched paths again, to biology. “I took 7.012 [MIT’s introductory biology course] with Eric Lander and Rob Weinberg,” she says. “I haven’t really looked back since.”

Lin recently completed her senior thesis in the lab of Jeroen Saeij, an assistant professor of biology, where she investigated Toxoplasma gondii, an infectious parasite that serves as a model for malaria because of its similarities to the parasite behind the mosquito-borne disease. Lin’s project looked at a specific protein found within Toxoplasma, and how that protein affects which genes are turned on and off in host cells invaded by the parasite.

With the help of a team in Saeij’s lab, Lin created two versions of the parasite — one with the protein in question, the other without — and infected host cells with them, comparing how the cells’ behavior differed in the two versions.

“We found that [the presence of this protein] was potentially changing the way that host cells sense nutrients,” Lin says. “Now the hypothesis, or at least the suspicion, is that it allows a parasite to usurp more nutrients from the host cell,” which in turn allows the parasite to grow and replicate faster.

In addition to her lab-based research, Lin has a passion for putting biology into practice: She has undertaken two service trips through MIT’s Global Poverty Initiative, both to a small Mexican village where farmers were struggling to increase their crop yields. While lab work is often concerned with pioneering high-tech methods, Lin says her experience in Mexico showed her that in real-world settings, great progress can be made simply by connecting people with tried-and-true resources. In the villagers’ case, the solution involved greenhouses, fertilizers and crop rotation — relatively simple strategies, but ones previously unfamiliar to these farmers.

“We have so much more access to information just because we’re students living in a more developed place,” Lin says. “We can Google anything that we want to find; we can look for people in our area who are experts in almost any field. When you’re in a rural community you just don’t have that. There’s no Internet, and there’s very little exchange of information between the city and the countryside.”

Lin’s experiences in Mexico gave her an appreciation for the challenges facing those in developing countries — but in fact, she has seen similar issues closer to home. Since her freshman year at the Institute, she has volunteered with Health Leads Boston, an organization that helps low-income patients access the social services they need, such as food stamps, subsidized housing and utility assistance.

Working at Health Leads “made me realize how many resources there are in Boston, but also how difficult they can be to access,” Lin says, adding that her most challenging case involved a pregnant patient with rheumatoid arthritis who lived two hours from Boston Medical Center and lacked personal transportation. Lin says she would often “run out of lecture and give [the patient] a call,” to make sure that the prearranged taxi had arrived on time.

“Sometimes — often, actually — it’s just about helping someone get the simple things they need,” Lin says.

Looking forward, Lin is drawn to the study of infectious diseases, which she sees as an ideal combination of biology, research and social issues. She is considering applying her Rhodes scholarship toward a master’s degree in medical anthropology at Oxford University in the U.K. before attending medical school, focusing on what she calls the “humanistic aspects of medicine,” such as the best way to get patients to adhere to a treatment plan and factors that lead to the spread of disease.

Whichever direction Lin’s career takes her, one thing’s for sure: No longer can anyone accuse her of being unmotivated.