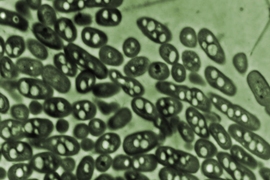

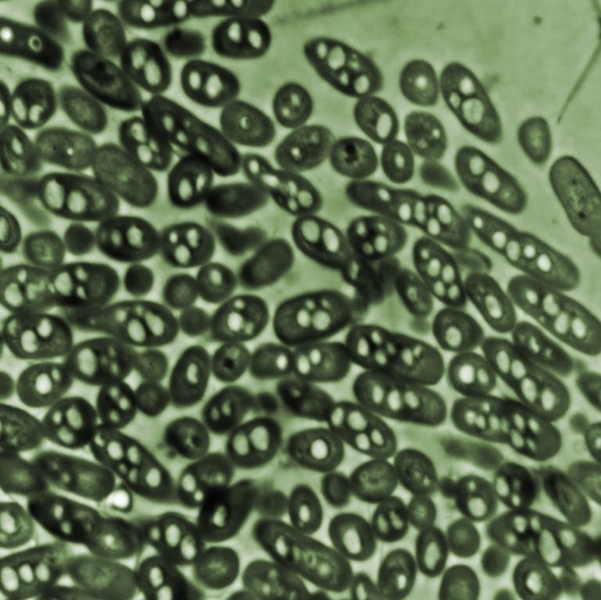

A humble soil bacterium called Ralstonia eutropha has a natural tendency, whenever it is stressed, to stop growing and put all its energy into making complex carbon compounds. Now scientists at MIT have taught this microbe a new trick: They’ve tinkered with its genes to persuade it to make fuel — specifically, a kind of alcohol called isobutanol that can be directly substituted for, or blended with, gasoline.

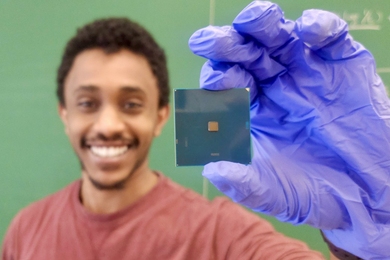

Christopher Brigham, a research scientist in MIT’s biology department who has been working to develop this bioengineered bacterium, is currently trying to get the organism to use a stream of carbon dioxide as its source of carbon, so that it could be used to make fuel out of emissions. Brigham is co-author of a paper on this research published this month in the journal Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology.

Brigham explains that in the microbe’s natural state, when its source of essential nutrients such as nitrate or phosphate is restricted, “it will go into carbon-storage mode,” essentially storing away food for later use when it senses that resources are limited.

“What it does is take whatever carbon is available, and stores it in the form of a polymer, which is similar in its properties to a lot of petroleum-based plastics,” Brigham says. By knocking out a few genes, inserting a gene from another organism and tinkering with the expression of other genes, Brigham and his colleagues were able to redirect the microbe to make fuel instead of plastic.

While the team is focusing on getting the microbe to use CO2 as a carbon source, with slightly different modifications the same microbe could also potentially turn almost any source of carbon, including agricultural waste or municipal waste, into useful fuel. In the laboratory, the microbes have been using fructose, a sugar, as their carbon source.

At this point, the MIT team — which includes chemistry graduate student Jingnan Lu, biology postdoc Claudia Gai, and is led by Anthony Sinskey, professor of biology — have demonstrated success in modifying the microbe’s genes so that it converts carbon into isobutanol in an ongoing process.

“We’ve shown that, in continuous culture, we can get substantial amounts of isobutanol,” Brigham says. Now, the researchers are focused on optimizing the system to increase the rate of production and designing bioreactors to scale the process up to industrial levels.

Unlike some bioengineered systems in which microbes produce a desired chemical within their bodies but have to be destroyed to retrieve the product, R. eutropha naturally expels the isobutanol into the surrounding fluid, where it can be continuously filtered out without stopping the production process, Brigham says. “We didn’t have to add a transport system to get it out of the cell,” he says.

A number of research groups are pursuing isobutanol production through various pathways, including other genetically modified organisms; at least two companies are already gearing up to produce it as a fuel, fuel additive or feedstock for chemical production. Unlike some proposed biofuels, isobutanol can be used in current engines with little or no modification, and has already been used in some racing cars.

Mark Silby, an assistant professor of biology at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, says, “This approach has several potential advantages over the production of ethanol from corn. Bacterial systems are scalable, in theory allowing production of large amounts of biofuel in a factory-like environment.” He adds, “This system in particular has the potential to derive carbon from waste products or carbon dioxide, and thus is not competing with the food supply.” Overall, he says, “the potential impact of this approach is huge.”

The work is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy (ARPA-E).