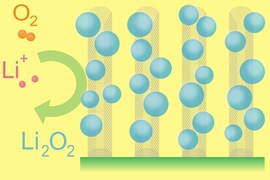

The work is a continuation of a project that last year demonstrated improved efficiency in lithium-air batteries through the use of noble-metal-based catalysts. In principle, lithium-air batteries have the potential to pack even more punch for a given weight than lithium-ion batteries because they replace one of the heavy solid electrodes with a porous carbon electrode that stores energy by capturing oxygen from air flowing through the system, combining it with lithium ions to form lithium oxides.

The new work takes this advantage one step further, creating carbon-fiber-based electrodes that are substantially more porous than other carbon electrodes, and can therefore more efficiently store the solid oxidized lithium that fills the pores as the battery discharges.

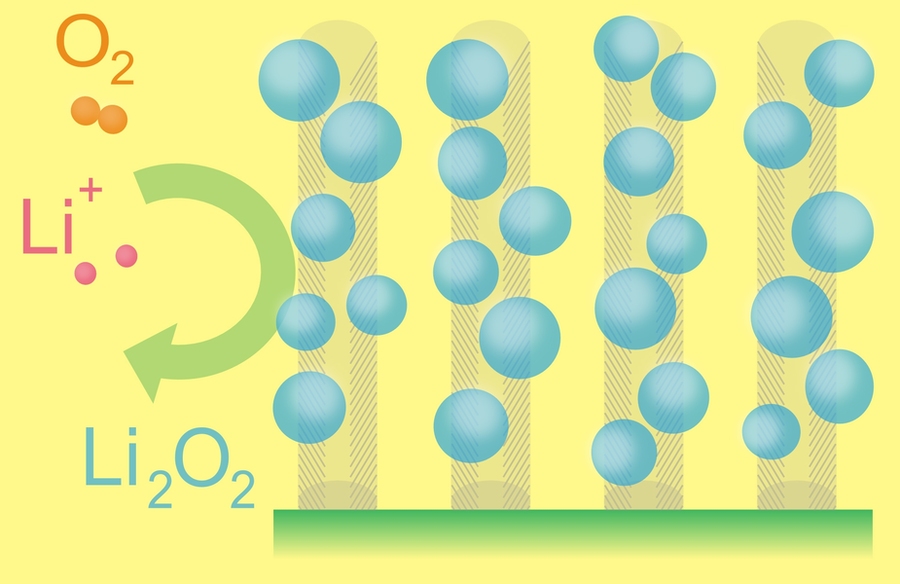

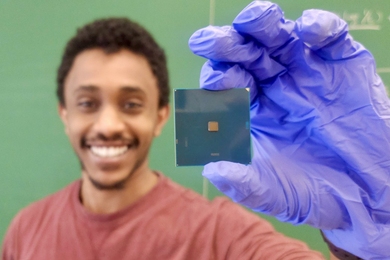

"We grow vertically aligned arrays of carbon nanofibers using a chemical vapor deposition process. These carpet-like arrays provide a highly conductive, low-density scaffold for energy storage," explains Robert Mitchell, a graduate student in MIT's Department of Materials Science and Engineering (DMSE) and co-author of a paper describing the new findings in the journal Energy and Environmental Science.

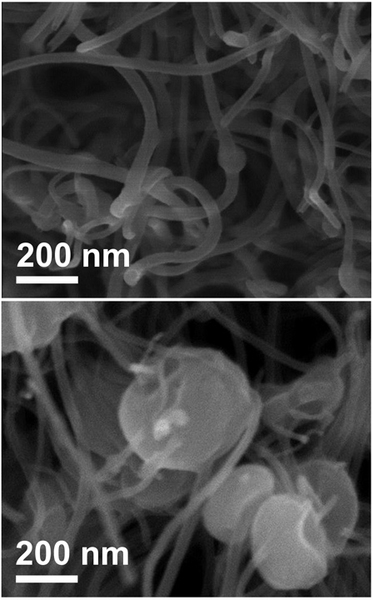

During discharge, lithium-peroxide particles grow on the carbon fibers, adds co-author Betar Gallant, a graduate student in MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering. In designing an ideal electrode material, she says, it's important to "minimize the amount of carbon, which adds unwanted weight to the battery, and maximize the space available for lithium peroxide," the active compound that forms during the discharging of lithium-air batteries.

"We were able to create a novel carpet-like material — composed of more than 90 percent void space — that can be filled by the reactive material during battery operation," says Yang Shao-Horn, the Gail E. Kendall Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science and Engineering and senior author of the paper. The other senior author of the paper is Carl Thompson, the Stavros Salapatas Professor of Materials Science and Engineering and interim head of DMSE.

In earlier lithium-air battery research that Shao-Horn and her students reported last year, they demonstrated that carbon particles could be used to make efficient electrodes for lithium-air batteries. In that work, the carbon structures were more complex but only had about 70 percent void space.

The gravimetric energy stored by these electrodes — the amount of power they can store for a given weight — "is among the highest values reported to date, which shows that tuning the carbon structure is a promising route for increasing the energy density of lithium-air batteries," Gallant says. The result is an electrode that can store four times as much energy for its weight as present lithium-ion battery electrodes.

In the paper published last year, the team had estimated the kinds of improvement in gravimetric efficiency that might be achieved with lithium-air batteries; this new work "realizes this gravimetric gain," Shao-Horn says. Further work is still needed to translate these basic laboratory advances into a practical commercial product, she cautions.

Because the electrodes take the form of orderly "carpets" of carbon fibers — unlike the randomly arranged carbon particles in other electrodes — it is relatively easy to use a scanning electron microscope to observe the behavior of the electrodes at intermediate states of charge. The researchers say this ability to observe the process, an advantage that they had not anticipated, is a critical step toward further improving battery performance. For example, it could help explain why existing systems degrade after many charge-discharge cycles.

Ji-Guang Zhang, a laboratory fellow in battery technology at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, says this is "original and high-quality work." He adds that this research "demonstrates a very unique approach to preparing high-capacity electrodes for lithium-air batteries."