Four students who spent the spring semester determining whether MIT should install rooftop wind turbines uncovered both good news and not-so-good news.

The group was blown away by MIT students' overwhelming support of wind power on campus. The problem is that even an MIT-owned 29-story apartment building--the best option for locating a wind turbine--does not get a whole lot of wind. Still, Team Wind recommended placing a 12-foot diameter wind turbine on the building to help make a dent in MIT's electric bill, offset carbon dioxide emissions and serve as an educational resource for future projects related to energy and wind.

First-year students Richard Bates, Samantha Fox, KT McCusker and Katie Pesce were among a dozen MIT students in a class--offered for the first time last semester--that investigated ways to help MIT and the City of Cambridge reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions.

On May 11, Team Wind, as the four called themselves, presented their results assessing the economic, technical, aesthetic and policy issues connected with installing small and micro-sized wind turbines on MIT buildings to capture wind energy. In the audience were MIT and Cambridge decision-makers who could help implement the proposed projects.

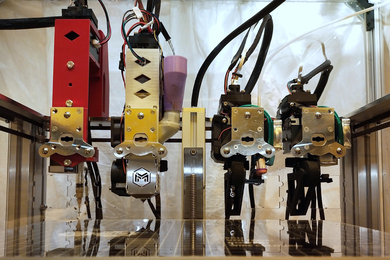

Nowhere near the scale of commercial turbines with 100-meter-wide blades, the Skystream 3.7 made by Arizona-based Southwest Windpower has compact 12-foot rotors.

The Skystream system has an installed cost of around $7,900, although it has never been installed on a building before, and would be eligible for around $2,700 in rebates through the Massachusetts Technology Collaborative. It would provide 2,600 kilowatt hours (kWh) of energy annually. The cost to MIT would be nine cents per kWh compared with 15 cents per kWh from a utility company. A turbine installed on Eastgate would have a payback time of 11 years, the group calculated.

"It has high value proportional to its size and the potential for good cost savings," said Dan Wesolowski, a materials science and engineering graduate student who served as a teaching assistant and helped develop the course. Nevertheless, it would take a wind turbine one year to offset the amount of greenhouse gases than MIT produces in six minutes.

The students measured wind speeds at seven campus locations before settling on Eastgate tower, which houses graduate students and their families in 203 apartments at the east end of campus. The building is close to the Charles River, generally considered a good option for wind power density. A site needs class 3 wind power density, translating to mean wind speeds of around 12 mph, to be economically attractive. MIT's campus is largely class 1.

The new class, "Energy, Environment and Society," focused on solving real-world problems. Jeffrey I. Steinfeld, professor of chemistry and director of the Laboratory for Energy and Environment (LFEE) education program; Jefferson W. Tester, the H.P. Meissner Professor of Chemical Engineering; and Amanda Graham, manager of the LFEE education program, designed and led the class, aided by three graduate student teaching assistants.

"We feel strongly that having students develop projects leading to real-world products rather than more abstract outcomes provides a very different learning experience," Graham said. "The students meet the people who care about the material they generate, and there's a sudden shift in their investment and motivation that we hope will deepen their experience and commitment and extend their learning."

The d'Arbeloff Fund for Excellence in Education supported the development of this class.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on June 6, 2007 (download PDF).