A broken motor in an automated machine can bring production on a busy factory floor to a halt. If engineers can’t find a replacement part, they may have to order one from a distributor hundreds of miles away, leading to costly production delays.

It would be easier, faster, and cheaper to make a new motor onsite, but fabricating electric machines typically requires specialized equipment and complicated processes, which restricts production to a few manufacturing centers.

In an effort to democratize the manufacturing of complex devices, MIT researchers have developed a multimaterial 3D-printing platform that could be used to fully print electric machines in a single step.

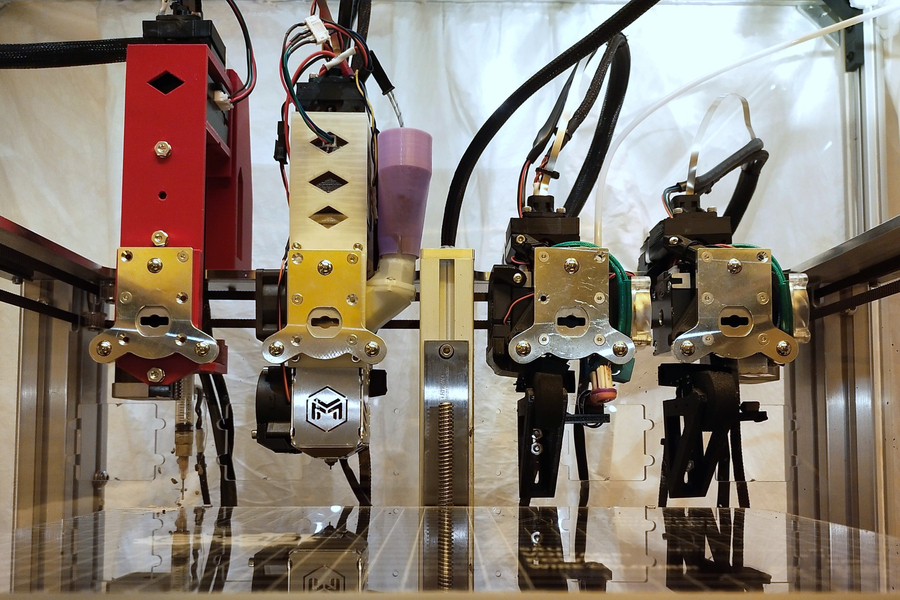

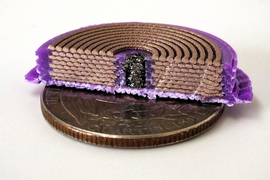

They designed their system to process multiple functional materials, including electrically conductive materials and magnetic materials, using four extrusion tools that can handle varied forms of printable material. The printer switches between extruders, which deposit material by squeezing it through a nozzle as it fabricates a device one layer at a time.

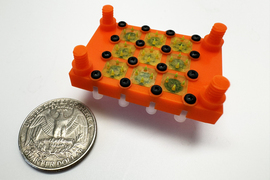

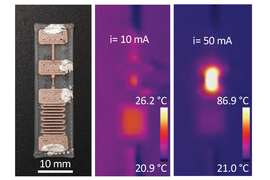

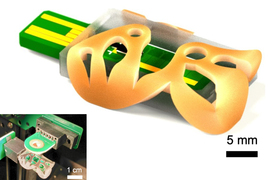

The researchers used this system to produce a fully 3D-printed electric linear motor in a matter of hours using five materials. They only needed to perform one post-processing step for the motor to be fully functional.

The assembled device performed as well or better than similar motors that require more complex fabrication methods or additional post-processing steps.

In the long run, this 3D printing platform could be used to rapidly fabricate customizable electronic components for robots, vehicles, or medical equipment with much less waste.

“This is a great feat, but it is just the beginning. We have an opportunity to fundamentally change the way things are made by making hardware onsite in one step, rather than relying on a global supply chain. With this demonstration, we’ve shown that this is feasible,” says Luis Fernando Velásquez-García, a principal research scientist in MIT’s Microsystems Technology Laboratories (MTL) and senior author of a paper describing the 3D-printing platform, which appears today in Virtual and Physical Prototyping.

He is joined on the paper by electrical engineering and computer science (EECS) graduate students Jorge Cañada, who is the lead author, and Zoey Bigelow.

More materials

The researchers focused on extrusion 3D printing, a tried-and-true method that involves squirting material through a nozzle to fabricate an object one layer at a time.

To fabricate an electric machine, the researchers needed to be able to switch between multiple materials that offer different functionalities. For instance, the device would need an electrically conductive material to carry electric current and hard magnetic materials to generate magnetic fields for efficient energy conversion.

Most multimaterial extrusion 3D printing systems can only switch between two materials that come in the same form, such as filament or pellets, so the researchers had to design their own. They retrofit an existing printer with four extruders that can each handle a different form of feedstock.

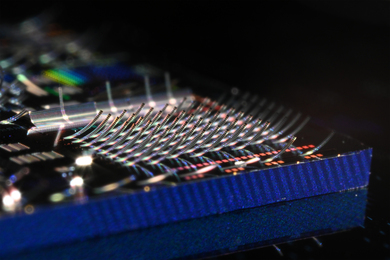

They carefully designed each extruder to balance the requirements and limitations of the material. For instance, the electrically conductive material must be able to harden without the use of too much heat or UV light because this can degrade the dielectric material.

At the same time, the best-performing electrically conductive materials come in the form of inks which are extruded using a pressure system. This process has vastly different requirements than standard extruders that use heated nozzles to squirt melted filament or pellets.

“There were significant engineering challenges. We had to figure out how to marry together many different expressions of the same printing method — extrusion — seamlessly into one platform,” Velásquez-García says.

The researchers utilized strategically placed sensors and a novel control framework so each tool is picked up and put down consistently by the platform’s robotic arms, and so each nozzle moves precisely and predictably.

This ensures each layer of material lines up properly — even a slight misalignment can derail the performance of the finished machine.

Making a motor

After perfecting the printing platform, the researchers fabricated a linear motor, which generates straight-line motion (as opposed to a rotating motor, like the one in a car). Linear motors are used in applications like pick-and-place robotics, optical systems, and baggage conveyers.

They fabricated the motor in about three hours and only needed to magnetize the hard magnetic materials after printing to enable full functionality. The researchers estimate total material costs would be about 50 cents per device. Their 3D-printed motor was able to generate several times more actuation than a common type of linear engine that relies on complex hydraulic amplifiers.

“Even though we are excited by this engine and its performance, we are equally inspired because this is just an example of so many other things to come that could dramatically change how electronics are manufactured,” says Velásquez-García.

In the future, the researchers want to integrate the magnetization step into the multimaterial extrusion process, demonstrate the fabrication of fully 3D-printed rotary electrical motors, and add more tools to the platform to enable monolithic fabrication of more complex electronic devices.

This research is funded, in part, by Empiriko Corporation and the La Caixa Foundation.