James Baldwin was a prodigy. That is not the first thing most people associate with a writer who once declared that he “had no childhood” and whose work often elides the details of his early life in New York, in the 1920s and 1930s. Still, by the time Baldwin was 14, he was a successful church preacher, excelling in a role otherwise occupied by adults.

Throw in the fact that Baldwin was reading Dostoyevsky by the fifth grade, wrote “like an angel” according to his elementary school principal, edited his middle school periodical, and wrote for his high school magazine, and it’s clear he was a precocious wordsmith.

These matters are complicated, of course. To MIT scholar Joshua Bennett, Baldwin’s writings reveal enough for us to conclude that his childhood was marked by a “relentless introspection” as he sought to come to terms with the world. Beyond that, Bennett thinks, some of Baldwin’s work, and even the one children’s book he wrote, yields “messages of persistence,” recognizing the need for any child to receive encouragement and education.

And if someone as precocious as Baldwin still needed cultivation, then virtually everyone does. If we act is if talent blossoms on its own, we are ignoring the vital role communities, teachers, and families play in helping artists — or anyone — develop their skills.

“We talk as if these people emerged ex nihilo,” Bennett says. “When all along the way, there were people who cultivated them, and our children deserve the same — all of the children of the world. We have a dominant model of genius that is fundamentally flawed, in that it often elides the role of communities and cultural institutions.”

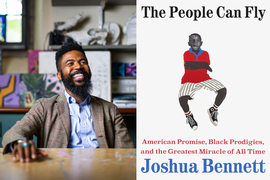

Bennett explores these issues in a new book, “The People Can Fly: American Promise, Black Prodigies, and the Greatest Miracle of All Time,” published this week by Hachette. A literary scholar and poet himself, Bennett is the Distinguished Chair of the Humanities at MIT and a professor of literature.

“The People Can Fly” accomplishes many kinds of work at once: Bennett offers a series of profiles, carefully wrought to see how some prominent figures were able to flourish from childhood forward. And he closely reads their works for indications about how they understood the shape of their own lives. In so doing, Bennett underscores the significance of the social settings that prodigious talents grow up in. For good measure, he also offers reflections on his own career trajectory and encounters with these artists, driving home their influence and meaning.

Reading about these many prodigies, one by one, helps readers build a picture of the realities, and complications, of trying to sustain early promise.

“It’s part of what I tell my students — the individual is how you get to the universal,” Bennett says. “It doesn’t mean I need to share certain autobiographical impulses with, say, Hemingway. It’s just that I think those touchpoints exist in all great works of art.”

Space odyssey

For Bennett, the idea of writing about prodigies grew naturally from his research and teaching, which ranges broadly in American and global literature. Bennett began contemplating “the idea of promise as this strange, idiosyncratic quality, this thing we see through various acts, perhaps something as simple as a little riff you hear a child sing, an element of their drawings, or poems.” At the same time, he notes, people struggle with “the weight of promise. There is a peril that can come along with promise. Promise can be taken away.”

Ultimately, Bennett adds, “I started thinking a little more about what promise has meant in African American communities,” in particular. Ranging widely in the book, Bennett consistently loops back to a core focus on the ideals, communities, and obstacles many Black artists grew up with. These artists and intellectuals include Malcolm X, Gwendolyn Brooks, Stevie Wonder, and the late poet and scholar Nikki Giovanni.

Bennett’s chapter on Giovanni shows his own interest in placing an artist’s life in historical context, and picks up on motifs relating back to childhood and personal promise.

Giovanni attended Fisk University early, enrolling at 17. Later she enrolled in Columbia University’s Masters of Fine Arts program, where poetry students were supposed to produce publishable work in a two-year program. In her first year, Giovanni’s poetry collection, “Black Feeling, Black Talk,” not only got published but became a hit, selling 10,000 copies. She left the program early — without a degree, since it required two years of residency. In short, she was always going places.

Giovanni went on to become one of the most celebrated poets of her time, and spent decades on the faculty at Virginia Tech. One idea that kept recurring in her work: dreams of space exploration. Giovanni’s work transmitted a clear enthusiasm for exploring the stars.

“Looking through her work, you see space travel everywhere,” Bennett says. “Even in her most prominent poem, ‘Ego trippin (there may be a reason why),’ there is this sense of someone who’s soaring over the landscape — ‘I’m so hip even my errors are correct.’ There is this idea of an almost divine being.”

That enthusiasm was accompanied by the recognition that astronauts, at least at one time, emerged from a particular slice of society. Indeed, Giovanni at many times publicly called for more opportunities for more Americans to become astronauts. A pressing issue, for her, was making dreams achievable for more people.

“Nikki Giovanni is very invested in these sorts of questions, as a writer, as an educator, and as a big thinker,” Bennett says. “This kind of thinking about the cosmos is everywhere in her work. But inside of that is a critique, that everyone should have a chance to expand the orbit of their dreaming. And dream of whatever they need to.”

And as Bennett draws out in “The People Can Fly,” stories and visions of flying have run deep in Black culture, offering a potent symbolism and a mode of “holding on to a deeper sense that the constraints of this present world are not all-powerful or everlasting. The miraculous is yet available. The people could fly, and still can.”

Children with promise, families with dreams

Other artists have praised “The People Can Fly.” The actor, producer, and screenwriter Lena Waithe has said that “Bennett’s poetic nature shines through on every page. … This book is a masterclass in literature and a necessary reminder to cherish the child in all of us.”

Certainly Bennett brings a vast sense of scope to “The People Can Fly,” ranging across centuries of history. Phillis Wheatley, a former enslaved woman whose 1773 poetry collection was later praised by George Washington, was an early American prodigy, studying the classics as a teenager and releasing her work at age 20. Mae Jemison, the first Black female astronaut, enrolled in Stanford University at age 16, spurred by family members who taught her about the stars. All told, Bennett weaves together a scholarly tapestry about hope, ambition, and, at times, opportunity.

Often, that hope and ambition belong to whole families, not just one gifted child. As Nikki Giovanni herself quipped, while giving the main address at MIT’s annual Martin Luther King convocation in 1990, “the reason you go to college is that it makes your mother happy.”

Bennett can relate, having come from a family where his mother was the only prior relative to have attended college. As a kid in the 1990s, growing up in Yonkers, New York, he had a Princeton University sweatshirt, inspired by his love of the television program “The Fresh Prince of Bel Air.” The program featured a character named Phillip Banks — popularly known as “Uncle Phil” — who was, within the world of the show, a Princeton alumnus.

“I would ask my Mom, ‘How do I get into Princeton?’” Bennett recalls. “She would just say, ‘Study hard, honey.’ No one but her had even been to college in my family. No one had been to Princeton. No one had set foot on Princeton University’s campus. But the idea that was possible in the country we lived in, for a woman who was the daughter of two sharecroppers, and herself grew up in a tenement with her brothers and sister, and nonetheless went on to play at Carnegie Hall and get a college degree and buy her mother a color TV — it’s fascinating to me.”

The postscript to that anecdote is that Bennett did go on to earn his PhD from Princeton. Behind many children with promise are families and communities with dreams for those kids.

“There’s something to it I refuse to relinquish,” Bennett says. “My mother’s vision was a powerful and persistent one — she believed that the future also belonged to her children.”