MIT researchers have designed silicon structures that can perform calculations in an electronic device using excess heat instead of electricity. These tiny structures could someday enable more energy-efficient computation.

In this computing method, input data are encoded as a set of temperatures using the waste heat already present in a device. The flow and distribution of heat through a specially designed material forms the basis of the calculation. Then the output is represented by the power collected at the other end, which is thermostat at a fixed temperature.

The researchers used these structures to perform matrix vector multiplication with more than 99 percent accuracy. Matrix multiplication is the fundamental mathematical technique machine-learning models like LLMs utilize to process information and make predictions.

While the researchers still have to overcome many challenges to scale up this computing method for modern deep-learning models, the technique could be applied to detect heat sources and measure temperature changes in electronics without consuming extra energy. This would also eliminate the need for multiple temperature sensors that take up space on a chip.

“Most of the time, when you are performing computations in an electronic device, heat is the waste product. You often want to get rid of as much heat as you can. But here, we’ve taken the opposite approach by using heat as a form of information itself and showing that computing with heat is possible,” says Caio Silva, an undergraduate student in the Department of Physics and lead author of a paper on the new computing paradigm.

Silva is joined on the paper by senior author Giuseppe Romano, a research scientist at MIT’s Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies. The research appears today in Physical Review Applied.

Turning up the heat

This work was enabled by a software system the researchers previously developed that allows them to automatically design a material that can conduct heat in a specific manner.

Using a technique called inverse design, this system flips the traditional engineering approach on its head. The researchers define the functionality they want first, then the system uses powerful algorithms to iteratively design the best geometry for the task.

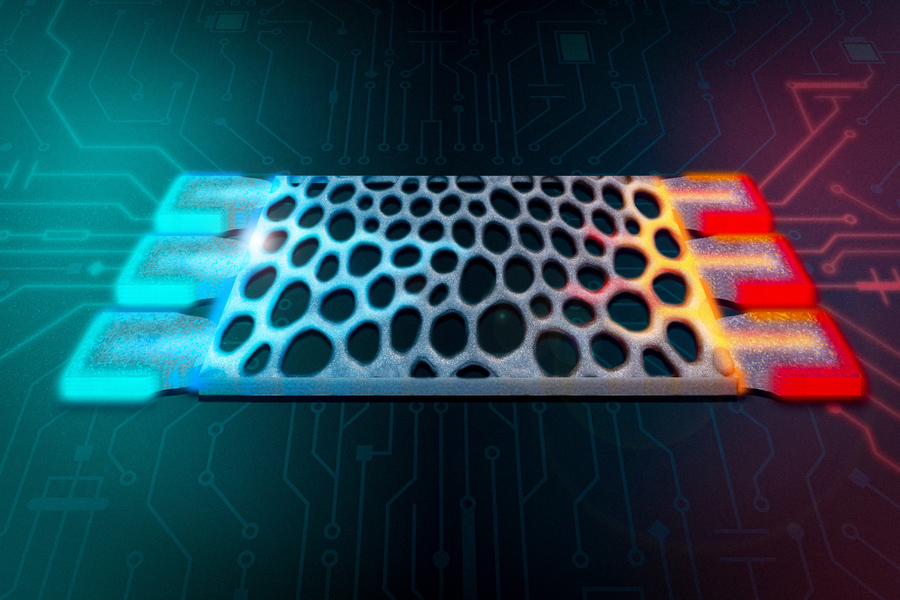

They used this system to design complex silicon structures, each roughly the same size as a dust particle, that can perform computations using heat conduction. This is a form of analog computing, in which data are encoded and signals are processed using continuous values, rather than digital bits that are either 0s or 1s.

The researchers feed their software system the specifications of a matrix of numbers that represents a particular calculation. Using a grid, the system designs a set of rectangular silicon structures filled with tiny pores. The system continually adjusts each pixel in the grid until it arrives at the desired mathematical function.

Heat diffuses through the silicon in a way that performs the matrix multiplication, with the geometry of the structure encoding the coefficients.

Image: Courtesy of Caio Silva, MIT

“These structures are far too complicated for us to come up with just through our own intuition. We need to teach a computer to design them for us. That is what makes inverse design a very powerful technique,” Romano says.

But the researchers ran into a problem. Due to the laws of heat conduction, which impose that heat goes from hot to cold regions, these structures can only encode positive coefficients.

They overcame this problem by splitting the target matrix into its positive and negative components and representing them with separately optimized silicon structures that encode positive entries. Subtracting the outputs at a later stage allows them to compute negative matrix values.

They can also tune the thickness of the structures, which allows them to realize a greater variety of matrices. Thicker structures have greater heat conduction.

“Finding the right topology for a given matrix is challenging. We beat this problem by developing an optimization algorithm that ensures the topology being developed is as close as possible to the desired matrix without having any weird parts,” Silva explains.

Microelectronic applications

The researchers used simulations to test the structures on simple matrices with two or three columns. While simple, these small matrices are relevant for important applications, such as fusion sensing and diagnostics in microelectronics.

The structures performed computations with more than 99 percent accuracy in many cases.

However, there is still a long way to go before this technique could be used for large-scale applications such as deep learning, since millions of structures would need to be tiled together. As the matrices become more complicated, the structures become less accurate, especially when there is a large distance between the input and output terminals. In addition, the devices have limited bandwidth, which would need to be greatly expanded if they were to be used for deep learning.

But because the structures rely on excess heat, they could be directly applied for tasks like thermal management, as well as heat source or temperature gradient detection in microelectronics.

“This information is critical. Temperature gradients can cause thermal expansion and damage a circuit or even cause an entire device to fail. If we have a localized heat source where we don’t want a heat source, it means we have a problem. We could directly detect such heat sources with these structures, and we can just plug them in without needing any digital components,” Romano says.

Building on this proof-of-concept, the researchers want to design structures that can perform sequential operations, where the output of one structure becomes an input for the next. This is how machine-learning models perform computations. They also plan to develop programmable structures, enabling them to encode different matrices without starting from scratch with a new structure each time.