In Washington, where conversations about Russia often center on a single name, political science doctoral candidate Suzanne Freeman is busy redrawing the map of power in autocratic states. Her research upends prevailing narratives about Vladimir Putin’s Russia, asking us to look beyond the individual to understand the system that produced him.

“The standard view is that Putin originated Russia’s system of governance and the way it engages with the world,” Freeman explains. “My contention is that Putin is a product of a system rather than its author, and that his actions are very consistent with the foreign policy beliefs of the organization in which he was educated.”

That organization — the KGB and its successor agencies — stands at the center of Freeman’s dissertation, which examines how authoritarian intelligence agencies intervene in their own states’ foreign policy decision-making processes, particularly decisions about using military force.

Dismantling the “yes men” myth

Past scholarship has relied on an oversimplified characterization of intelligence agencies in authoritarian states. “The established belief that I’m challenging is essentially that autocrats surround themselves with ‘yes’ men,” Freeman says. She notes that this narrative stems in great part from a famous Soviet failure, when intelligence officers were too afraid to contradict Stalin’s belief that Nazi Germany wouldn’t invade in 1941.

Freeman’s research reveals a far more complex reality. Through extensive archival work, including newly declassified documents from Lithuania, Moldova, and Poland, she shows that intelligence agencies in authoritarian regimes actually have distinct foreign policy preferences and actively work to advance them.

“These intelligence agencies are motivated by their organizational interests, seeking to survive and hold power inside and beyond their own borders,” Freeman says.

When an international situation threatens those interests, authoritarian intelligence agencies may intervene in the policy process using strategies Freeman has categorized in an innovative typology: indirect manipulation (altering collected intelligence), direct manipulation (misrepresenting analyzed intelligence), preemption in the field (unauthorized actions that alter a foreign crisis), and coercion (threats against political leadership).

“By intervene, I mean behaving in some way that’s inappropriate in accordance with what their mandate is,” Freeman explains. That mandate includes providing policy advice. “But sometimes intelligence agencies want to make their policy advice look more attractive by manipulating information,” she notes. “They may change the facts out on the ground, or in very rare circumstances, coerce policymakers.”

From Soviet archives to modern Russia

Rather than studying contemporary Russia alone, Freeman uses historical case studies of the Soviet Union’s KGB. Her research into this agency’s policy intervention covers eight foreign policy crises between 1950 and 1981, including uprisings in Eastern Europe, the Sino-Soviet border dispute, and the Soviet-Afghan War.

What she discovered contradicts prior assumptions that the agency was primarily a passive information provider. “The KGB had always been important for Soviet foreign policy and gave policy advice about what they thought should be done,” she says. Intelligence agencies were especially likely to pursue policy intervention when facing a “dual threat:” domestic unrest sparked by foreign crises combined with the loss of intelligence networks abroad.

This organizational motivation, rather than simply following a leader’s preferences, drove policy recommendations in predictable ways.

Freeman sees striking parallels to Russia’s recent actions in Ukraine. “This dual organizational threat closely mirrors the threat that the KGB faced in Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, and Poland from 1980 to 1981,” she explains. After 2014, Ukrainian intelligence reform weakened Russian intelligence networks in the country — a serious organizational threat to Russia’s security apparatus.

“Between 2014 and 2022, this network weakened,” Freeman notes. “We know that Russian intelligence had ties with a polling firm in Ukraine, where they had data saying that 84 percent of the population would view them as occupiers, that almost half of the Ukrainian population was willing to fight for Ukraine.” In spite of these polls, officers recommended going into Ukraine anyway.

This pattern resembles the KGB’s advocacy for invading Afghanistan using the manipulation of intelligence — a parallel that helps explain Russia’s foreign policy decisions beyond just Putin’s personal preferences.

Scholarly detective work

Freeman’s research innovations have allowed her to access previously unexplored material. “From a methodological perspective, it’s new archival material, but it’s also archival material from regions of a country, not the center,” she explains.

In Moldova, she examined previously classified KGB documents: huge amounts of newly available and unstructured documents that provided details into how anti-Soviet sentiment during foreign crises affected the KGB.

Freeman’s willingness to search beyond central archives distinguishes her approach, especially valuable as direct research in Russia becomes increasingly difficult. “People who want to study Russia or the Soviet Union who are unable to get to Russia can still learn very meaningful things, even about the central state, from these other countries and regions.”

From Boston to Moscow to MIT

Freeman grew up in Boston in an academic, science-oriented family; both her parents were immunologists. Going against the grain, she was drawn to history, particularly Russian and Soviet history, beginning in high school.

“I was always curious about the Soviet Union and why it fell apart, but I never got a clear answer from my teachers,” says Freeman. “This really made me want to learn more and solve that puzzle myself."

At Columbia University, she majored in Slavic studies and completed a master’s degree at the School of International and Public Affairs. Her undergraduate thesis examined Russian military reform, a topic that gained new relevance after Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine.

Before beginning her doctoral studies at MIT, Freeman worked at the Russia Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College, researching Russian military strategy and doctrine. There, surrounded by scholars with political science and history PhDs, she found her calling.

“I decided I wanted to be in an academic environment where I could do research that I thought would prove valuable,” she recalls.

Bridging academia and public education

Beyond her core research, Freeman has established herself as an innovator in war-gaming methodology. With fellow PhD student Benjamin Harris, she co-founded the MIT Wargaming Working Group, which has developed a partnership with the Naval Postgraduate School to bring mid-career military officers and academics together for annual simulations.

Their work on war-gaming as a pedagogical tool resulted in a peer-reviewed publication in PS: Political Science & Politics titled “Crossing a Virtual Divide: Wargaming as a Remote Teaching Tool.” This research demonstrates that war games are effective tools for active learning even in remote settings and can help bridge the civil-military divide.

When not conducting research, Freeman works as a tour guide at the International Spy Museum in Washington. “I think public education is important — plus they have a lot of really cool KGB objects,” she says. “I felt like working at the Spy Museum would help me keep thinking about my research in a more fun way and hopefully help me explain some of these things to people who aren’t academics.”

Looking beyond individual leaders

Freeman’s work offers vital insight for policymakers who too often focus exclusively on autocratic leaders, rather than the institutional systems surrounding them. “I hope to give people a new lens through which to view the way that policy is made,” she says. “The intelligence agency and the type of advice that it provides to political leadership can be very meaningful.”

As tensions with Russia continue, Freeman believes her research provides a crucial framework for understanding state behavior beyond individual personalities. “If you're going to be negotiating and competing with these authoritarian states, thinking about the leadership beyond the autocrat seems very important.”

Currently completing her dissertation as a predoctoral fellow at George Washington University’s Institute for Security and Conflict Studies, Freeman aims to contribute critical scholarship on Russia’s role in international security and inspire others to approach complex geopolitical questions with systematic research skills.

“In Russia and other authoritarian states, the intelligence system may endure well beyond a single leader’s reign,” Freeman notes. “This means we must focus not on the figures who dominate the headlines, but on the institutions that shape them.”

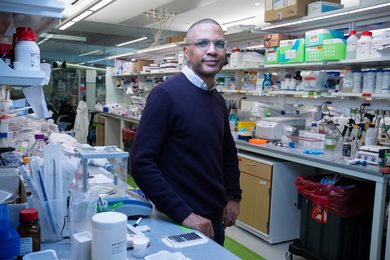

PhD candidate Suzanne Freeman reveals how intelligence agencies shape foreign policy in authoritarian states.

Publication Date:

Press Contact:

Caption:

As tensions with Russia continue, political science PhD candidate Suzanne Freeman believes her research provides a crucial framework for understanding state behavior beyond individual personalities. “If you're going to be negotiating and competing with these authoritarian states, thinking about the leadership beyond the autocrat seems very important,” she says.

Credits:

Photo: Chris Burns

Related Topics

Related Articles