As an undergraduate majoring in architecture, Dong Nyung Lee ’21 wasn’t sure how to respond when friends asked him what the study of architecture was about.

“I was always confused about how to describe it myself,” he says with a laugh. “I would tell them that it wasn’t just about a building, or a city, or a community. It’s a balance across different scales, and it has to touch everything all at once.”

As a graduate student enrolled in a design studio course last spring — 4.154 (Territory as Interior) — Lee and his classmates had to design a building that would serve a specific community in a specific location. The course, says Lee, gave him clarity as to “what architecture is all about.”

Designed by Roi Salgueiro Barrio, a lecturer in the MIT School of Architecture and Planning’s Department of Architecture, the coursework combines ecological principles, architectural design, urban economics, and social considerations to address real-world problems in marginalized or degraded areas.

“When we build, we always impact economies, mostly by the different types of technologies we use and their dependence on different types of labor and materials,” says Salgueiro Barrio. “The intention here was to think at both levels: the activities that can be accommodated, and how we can actually build something.”

Research first

Students were tasked with repurposing an abandoned fishing industry building on the Barbanza Peninsula in Galicia, Spain, and proposing a new economic activity for the building that would help regenerate the local economy. Working in groups, they researched the region’s material resources and fiscal sectors and designed detailed maps. This approach to constructing a building was new for Vincent Jackow a master's student in architecture.

“Normally in architecture, we work at the scale of one-to-100 meters,” he says. But this process allowed me to connect the dots between what the region offered and what could be built to support the economy.”

The aim of revitalizing this area is also a goal of Fundación RIA (RIA), a nonprofit think tank established by Pritzker Prize-winning architect David Chipperfield. RIA generates research and territorial planning with the goal of long-term sustainability of the built and natural environment in the Galicia region. During their spring break in March, the students traveled to Galicia, met with Chipperfield, business owners, fishermen, and farmers, and explored a variety of sites. They also consulted with the owner of the building they were to repurpose.

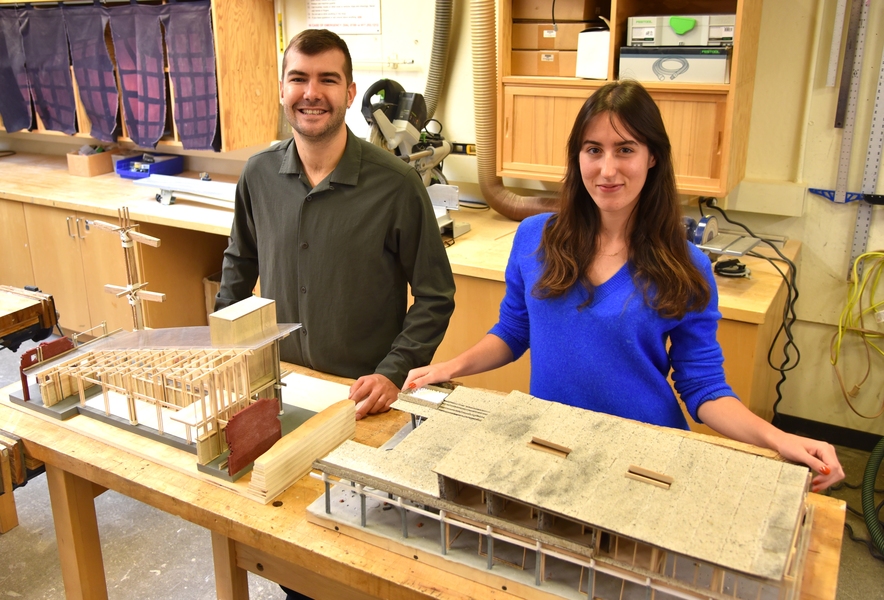

Returning to MIT, the students constructed nine detailed models. Master’s student Aleks Banaś says she took the studio because it required her to explore the variety of scales in an architectural project from territorial analysis to building detail, all while keeping the socio-economic aspect of design decisions in mind.

“I’m interested in how architecture can support local economies,” says Banaś. “Visiting Galicia was very special because of the communities we interacted with. We were no longer looking at articles and maps of the region; we were learning about day-to-day life. A lot of people shared with us the value of their work, which is not economically feasible.”

Banaś was impressed by the region’s strong maritime history and the generations of craftspeople working on timber boat-making. Inspired by the collective spirit of the region, she designed “House of Sea,” transforming the former cannery into a hub for community gathering and seafront activities. The reimagined building would accommodate a variety of functions including a boat-building workshop for the Ribeira carpenters’ association, a restaurant, and a large, covered section for local events such as the annual barnacle festival.

“I wanted to demonstrate how we can create space for an alternative economy that can host and support these skills and traditions,” says Banaś.

Jackow’s building — “La Nueva Cordelería,” or “New Rope Making” — was a facility using hemp to produce rope and hempcrete blocks (a construction material). The production of both “is very on-trend in the E.U.” and provides an alternative to petrochemical-based ropes for the region’s marine uses, says Jackow. The building would serve as a cultural hub, incorporating a café, worker housing, and offices. Even its very structure would also make use of the rope by joining timber with knots allowing the interior spaces to be redesigned.

Lee’s building was designed to engage with the forestry and agricultural industries.

“What intrigued me was that Galicia is heavily dependent on pulp production and wood harvesting,” he says. “I wanted to give value to the post-harvest residue.”

Lee designed a biochar plant using some of the concrete and terra cotta blocks on site. Biochar is made by heating the harvested wood residue through pyrolysis — thermal decomposition in an environment with little oxygen. The resulting biochar would be used by farmers for soil enhancement.

“The work demonstrated an understanding of the local resources and using them to benefit the revitalization of the area,” says Salgueiro Barrio, who was pleased with the results.

RIA was so impressed with the work that they held an exhibition at their gallery in Santiago de Compostela in August and September to highlight the importance of connecting academic research with the territory through student projects. Banaś interned with RIA over the summer working on multiple projects, including the plan and design for the exhibition. The challenge here, she says, was to design an exhibition of academic work for a general audience. The final presentation included maps, drawings, and photographs by the students.

For Lee, the course was more meaningful than any he has taken to date. Moving between the different scales of the project illustrated, for him, “the biggest challenge for a designer and an architect. Architecture is universal, and very specific. Keeping those dualities in focus was the biggest challenge and the most interesting part of this project. It hit at the core of what architecture is.”