When navigating a place that we’re only somewhat familiar with, we often rely on unique landmarks to help make our way. However, if we’re looking for an office in a brick building, and there are many brick buildings along our route, we might use a rule like looking for the second building on a street, rather than relying on distinguishing the building itself.

Until that ambiguity is resolved, we must hold in mind that there are multiple possibilities (or hypotheses) for where we are in relation to our destination. In a study of mice, MIT neuroscientists have now discovered that these hypotheses are explicitly represented in the brain by distinct neural activity patterns.

This is the first time that neural activity patterns that encode simultaneous hypotheses have been seen in the brain. The researchers found that these representations, which were observed in the brain’s retrosplenial cortex (RSC), not only encode hypotheses but also could be used by the animals to choose the correct way to go.

“As far as we know, no one has shown in a complex reasoning task that there’s an area in association cortex that holds two hypotheses in mind and then uses one of those hypotheses, once it gets more information, to actually complete the task,” says Mark Harnett, an associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences, a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and the senior author of the study.

Jakob Voigts PhD ’17, a former postdoc in Harnett’s lab and now a group leader at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Janelia Research Campus, is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in Nature Neuroscience.

Ambiguous landmarks

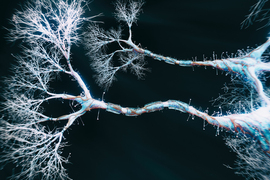

The RSC receives input from the visual cortex, the hippocampal formation, and the anterior thalamus, which it integrates to help guide navigation.

In a 2020 paper, Harnett’s lab found that the RSC uses both visual and spatial information to encode landmarks used for navigation. In that study, the researchers showed that neurons in the RSC of mice integrate visual information about the surrounding environment with spatial feedback of the mice’s own position along a track, allowing them to learn where to find a reward based on landmarks that they saw.

In their new study, the researchers wanted to delve further into how the RSC uses spatial information and situational context to guide navigational decision-making. To do that, the researchers devised a much more complicated navigational task than typically used in mouse studies. They set up a large, round arena, with 16 small openings, or ports, along the side walls. One of these openings would give the mice a reward when they stuck their nose through it. In the first set of experiments, the researchers trained the mice to go to different reward ports indicated by dots of light on the floor that were only visible when the mice get close to them.

Once the mice learned to perform this relatively simple task, the researchers added a second dot. The two dots were always the same distance from each other and from the center of the arena. But now the mice had to go to the port by the counterclockwise dot to get the reward. Because the dots were identical and only became visible at close distances, the mice could never see both dots at once and could not immediately determine which dot was which.

To solve this task, mice therefore had to remember where they expected a dot to show up, integrating their own body position, the direction they were heading, and path they took to figure out which landmark is which. By measuring RSC activity as the mice approached the ambiguous landmarks, the researchers could determine whether the RSC encodes hypotheses about spatial location. The task was carefully designed to require the mice to use the visual landmarks to obtain rewards, instead of other strategies like odor cues or dead reckoning.

“What is important about the behavior in this case is that mice need to remember something and then use that to interpret future input,” says Voigts, who worked on this study while a postdoc in Harnett’s lab. “It’s not just remembering something, but remembering it in such a way that you can act on it.”

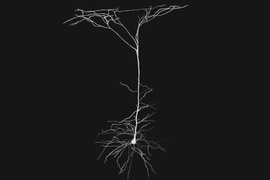

The researchers found that as the mice accumulated information about which dot might be which, populations of RSC neurons displayed distinct activity patterns for incomplete information. Each of these patterns appears to correspond to a hypothesis about where the mouse thought it was with respect to the reward.

When the mice get close enough to figure out which dot was indicating the reward port, these patterns collapsed into the one that represents the correct hypothesis. The findings suggest that these patterns not only passively store hypotheses, they can also be used to compute how to get to the correct location, the researchers say.

“We show that RSC has the required information for using this short-term memory to distinguish the ambiguous landmarks. And we show that this type of hypothesis is encoded and processed in a way that allows the RSC to use it to solve the computation,” Voigts says.

Interconnected neurons

When analyzing their initial results, Harnett and Voigts consulted with MIT Professor Ila Fiete, who had run a study about 10 years ago using an artificial neural network to perform a similar navigation task.

That study, previously published on bioRxiv, showed that the neural network displayed activity patterns that were conceptually similar to those seen in the animal studies run by Harnett’s lab. The neurons of the artificial neural network ended up forming highly interconnected low-dimensional networks, like the neurons of the RSC.

“That interconnectivity seems, in ways that we still don’t understand, to be key to how these dynamics emerge and how they’re controlled. And it’s a key feature of how the RSC holds these two hypotheses in mind at the same time,” Harnett says.

In his lab at Janelia, Voigts now plans to investigate how other brain areas involved in navigation, such as the prefrontal cortex, are engaged as mice explore and forage in a more naturalistic way, without being trained on a specific task.

“We’re looking into whether there are general principles by which tasks are learned,” Voigts says. “We have a lot of knowledge in neuroscience about how brains operate once the animal has learned a task, but in comparison we know extremely little about how mice learn tasks or what they choose to learn when given freedom to behave naturally.”

The research was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health, a Simons Center for the Social Brain at MIT postdoctoral fellowship, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines at MIT, funded by the National Science Foundation.