Farmers today face a number of challenges, from supply chain stability to nutrient and waste management. But hanging over everything is the need to maintain profitability amid changing markets and increased uncertainty.

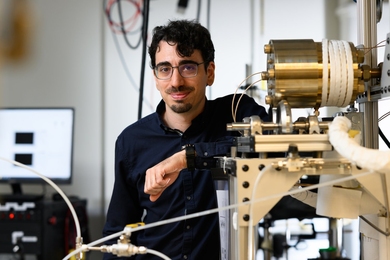

Fyto, founded by former MIT staff member Jason Prapas, is offering a highly automated cultivation system to address several of farmers’ biggest problems at once.

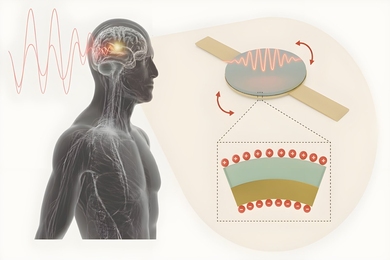

At the heart of Fyto’s system is Lemna, a genus of small aquatic plants otherwise known as duckweed. Most people have probably seen thick green mats of Lemna lying on top of ponds and swamps. But Lemna is also rich in protein and capable of doubling in biomass every two days. Fyto has built an automated cropping system that uses nitrogen-rich wastewater from dairy farms to grow Lemna in shallow pools on otherwise less productive farmland. On top of the pools, the company has built what it believes are the largest agricultural robots in the world, which monitor plant health and harvest the Lemna sustainably. The Lemna can then be used on farms as a high-protein cattle feed or fertilizer supplement.

Fyto’s systems are designed to rely on minimal land, water, and labor while creating a more sustainable, profitable food system.

“We developed from scratch a robotic system that takes the guesswork out of farming this crop,” says Prapas, who previously led the translational research program of MIT’s Tata Center. “It looks at the crop on a daily basis, takes inventory to know how many plants there are, how much should be harvested to have healthy growth the next day, can detect if the color is slightly off or there are nutrient deficiencies, and can suggest different interventions based on all that data.”

From kiddie pools to cow farms

Prapas’ first job out of college was with an MIT spinout called Green Fuel that harvested algae to make biofuel. He went back to school for a master’s and then a PhD in mechanical engineering, but he continued working with startups. Following his PhD at Colorado State University, he co-founded Factor[e] Ventures to fund and incubate startups focused on improving energy access in emerging markets.

Through that work, Prapas was introduced to MIT’s Tata Center for Technology and Design, a part of the MIT Energy Initiative.

“We were really interested in the new technologies being developed at the MIT Tata Center, and in funding new startups taking on some of these global climate challenges in emerging markets,” Prapas recalls. “The Tata Center was interested in making sure these technologies get put into practice rather than patented and put on a shelf somewhere. It was a good synergy.”

One of the people Prapas got to know was Rob Stoner, the founding director of the Tata Center, who encouraged Prapas to get more directly involved with commercializing new technologies. In 2017, Prapas joined the Tata Center as the translational research director. During that time, Prapas worked with MIT students, faculty, and staff to test their inventions in the real world. Much of that work involved innovations in agriculture.

“Farming is a fact of life for a lot of folks around the world — both subsistence farming but also producing food for the community and beyond,” Prapas says. “That has huge implications for water usage, electricity consumption, labor. For years, I’d been thinking about how we make farming a more attractive endeavor for people: How do we make it less back-breaking, more efficient, and more economical?”

Between his work at MIT and Factor[e], Prapas visited hundreds of farms around the world, where he started to think about the lack of good choices for farming inputs like animal feed and fertilizers. The problem represented a business opportunity.

Fyto began with kiddie pools. Prapas started growing aquatic plants in his backyard, using them as a fertilizer source for vegetables. The experience taught him how difficult it would be to train people to grow and harvest Lemna at large scales on farms.

“I realized we’d have to invent both the farming method — the agronomy — and the equipment and processes to grow it at scale cost effectively,” Prapas explains.

Prapas started discussing his ideas with others around 2019.

“The MIT and Boston ecosystems are great for pitching somewhat crazy ideas to willing audiences and seeing what sticks,” Prapas says. “There’s an intangible benefit of being at MIT, where you just can’t help but think of bold ideas and try putting them into practice.”

Prapas, who left MIT to lead Fyto in 2019, partnered with Valerie Peng ’17, SM ’19, then a graduate student at MIT who became his first hire.

“Farmers work so hard, and I have so much respect for what they do,” says Peng, who serves as Fyto’s head of engineering. “People talk about the political divide, but there’s a lot of alignment around using less, doing more with what you have, and making our food systems more resilient to drought, supply chain disruptions, and everything else. There’s more in common with everyone than you’d expect.”

A new farming method

Lemna can produce much more protein per acre than soy, another common source of protein on farms, but it requires a lot of nitrogen to grow. Fortunately, many types of farmers, especially large dairy farmers, have abundant nitrogen sources in the waste streams that come from washing out cow manure.

“These waste streams are a big problem: In California it’s believed to be one of the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the agriculture sector despite the fact that hundreds of crops are grown in California,” Prapas says.

For the last few years, Fyto has run its systems in pilots on farms, trialing the crop as feed and fertilizer before delivering to its customers. The systems Fyto has deployed so far are about 50 feet wide, but it is actively commissioning its newest version that’s 160 feet wide. Eventually, Fyto plans to sell the systems directly to farmers.

Fyto is currently awaiting California’s approval for use in feed, but Lemna has already been approved in Europe. Fyto has also been granted a fertilizer license on its plant-based fertilizer, with promising early results in trials, and plans to sell new fertilizer products this year.

Although Fyto is focused on dairy farms for its early deployments, it has also grown Lemna using manure from chicken, and Prapas notes that even people like cheese producers have a nitrogen waste problem that Fyto could solve.

“Think of us like a polishing step you could put on the end of any system that has an organic waste stream,” Prapas says. “In that situation, we’re interested in growing our crops on it. We’ve had very few things that the plant can’t grow on. Globally, we see this as a new farming method, and that means it’s got a lot of potential applications.”