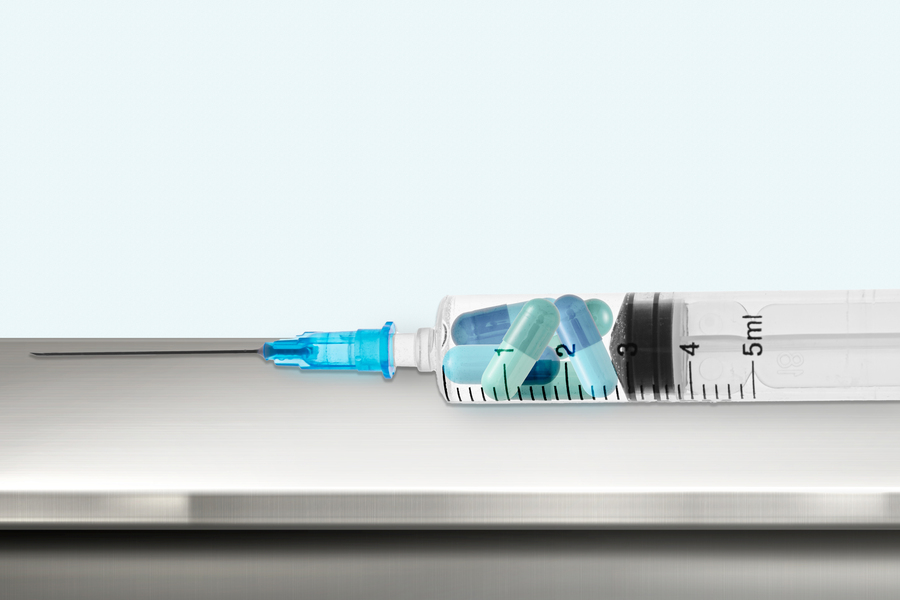

MIT engineers have devised a new way to deliver certain drugs in higher doses with less pain, by injecting them as a suspension of tiny crystals. Once under the skin, the crystals assemble into a drug “depot” that could last for months or years, eliminating the need for frequent drug injections.

This approach could prove useful for delivering long-lasting contraceptives or other drugs that need to be given for extended periods of time. Because the drugs are dispersed in a suspension before injection, they can be administered through a narrow needle that is easier for patients to tolerate.

“We showed that we can have very controlled, sustained delivery, likely for multiple months and even years through a small needle,” says Giovanni Traverso, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), an associate member of the Broad Institute, and the senior author of the study.

The lead authors of the paper, which appears today in Nature Chemical Engineering, are former MIT and BWH postdoc Vivian Feig, who is now an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford University; MIT graduate student Sanghyun Park; and Pier Rivano, a former visiting research scholar in Traverso’s lab.

Easier injections

This project began as part of an effort funded by the Gates Foundation to expand contraceptive options, particularly in developing nations.

“The overarching goal is to give women access to a lot of different formats for contraception that are easy to administer, compatible with being used in the developing world, and have a range of different timeframes of durations of action,” Feig says. “In our particular project, we were interested in trying to combine the benefits of long-acting implants with the ease of self-administrable injectables.”

There are marketed injectable suspensions available in the United States and other countries, but these drugs are dispersed throughout the tissue after injection, so they only work for about three months. Other injectable products have been developed that can form longer-lasting depots under the skin, but these typically require the addition of precipitating polymers that can make up 23 to 98 percent of the solution by weight, which can make the drug more difficult to inject.

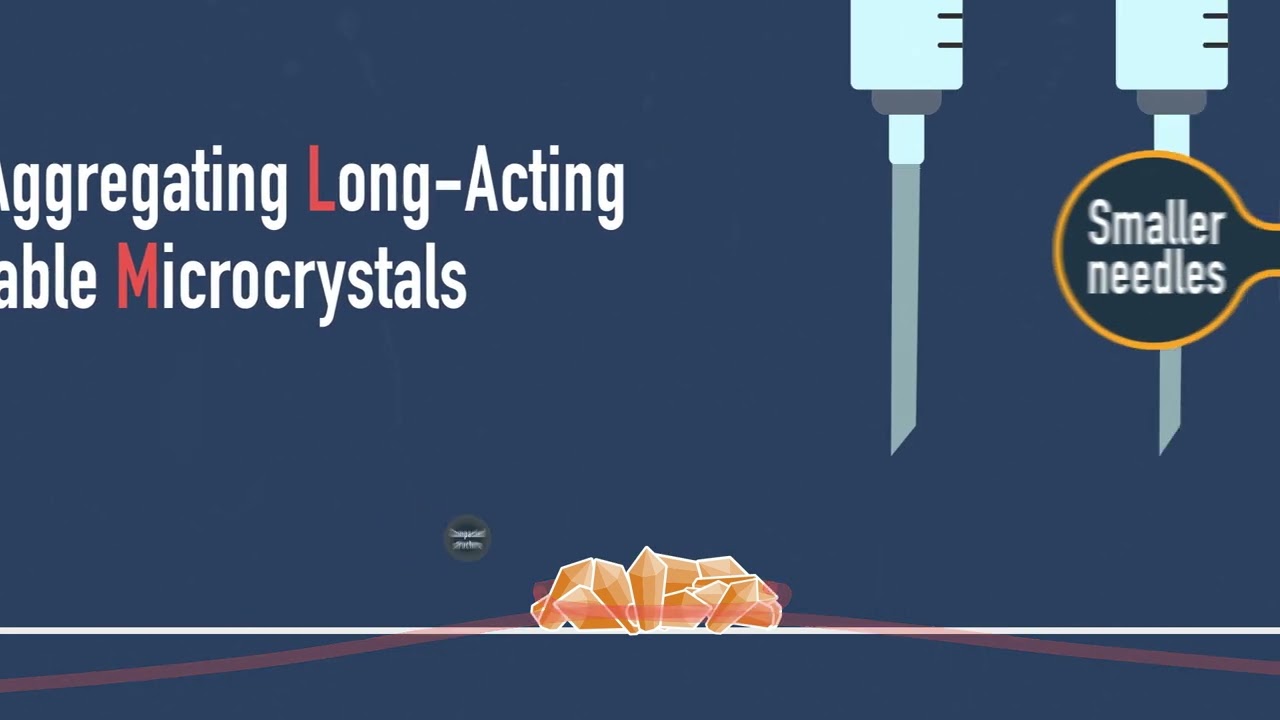

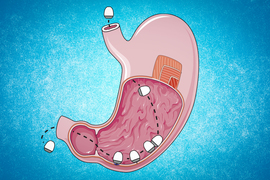

The MIT and BWH team wanted to create a formulation that could be injected through a small-gauge needle and last for at least six months and up to two years. They began working with a contraceptive drug called levonorgestrel, a hydrophobic molecule that can form crystals. The team discovered that suspending these crystals in a particular organic solvent caused the crystals to assemble into a highly compact implant after injection. Because this depot could form without needing large amounts of polymer, the drug formulation could still be easily injected through a narrow-gauge needle.

The solvent, benzyl benzoate, is biocompatible and has been previously used as an additive to injectable drugs. The team found that the solvent’s poor ability to mix with biological fluids is what allows the solid drug crystals to self-assemble into a depot under the skin after injection.

“The solvent is critical because it allows you to inject the fluid through a small needle, but once in place, the crystals self-assemble into a drug depot,” Traverso says.

By altering the density of the depot, the researchers can tune the rate at which the drug molecules are released into the body. In this study, the researchers showed they could change the density by adding small amounts of a polymer such as polycaprolactone, a biodegradable polyester.

“By incorporating a very small amount of polymers — less than 1.6 percent by weight — we can modulate the drug release rate, extending its duration while maintaining injectability. This demonstrates the tunability of our system, which can be engineered to accommodate a broader range of contraceptive needs as well as tailored dosing regimens for other therapeutic applications,” Park says.

Stable drug depots

The researchers tested their approach by injecting the drug solution subcutaneously in rats and showed that the drug depots could remain stable and release drug gradually for three months. After the three-month study ended, about 85 percent of the drug remained in the depots, suggesting that they could continue releasing the drugs for a much longer period of time.

“We anticipate that the depots could last for more than a year, based on our post-analysis of preclinical data. Follow-up studies are underway to further validate their efficacy beyond this initial proof-of-concept,” Park says.

Once the drug depots form, they are compact enough to be retrievable, allowing for surgical removal if treatment needs to be halted before the drug is fully released.

This approach could also lend itself to delivering drugs to treat neuropsychiatric conditions as well as HIV and tuberculosis, the researchers say. They are now moving toward assessing its translation to humans by conducting advanced preclinical studies to evaluate self-assembly in a more clinically relevant skin environment. “This is a very simple system in that it’s basically a solvent, the drug, and then you can add a little bit of bioresorbable polymer. Now we’re considering which indications do we go after: Is it contraception? Is it others? These are some of the things that we’re starting to look into as part of the next steps toward translation to humans,” Traverso says.

The research was funded, in part, by the Gates Foundation, the Karl van Tassel Career Development Professorship, the MIT Department of Mechanical Engineering, a Schmidt Science Fellows postdoctoral fellowship, the Rhodes Trust, a Takeda Fellowship, a Warren M. Rohsenow Fellowship, and a Kwangjeong Educational Foundation Fellowship.