When you’re challenging a century-old assumption, you’re bound to meet a bit of resistance. That’s exactly what John Joannopoulos and his group at MIT faced in 1998, when they put forth a new theory on how materials can be made to bend light in entirely new ways.

“Because it was such a big difference in what people expected, we wrote down the theory for this, but it was very difficult to get it published,” Joannopoulos told a capacity crowd in MIT’s Huntington Hall on Friday, as he delivered MIT’s James R. Killian, Jr. Faculty Achievement Award Lecture.

Joannopoulos’ theory offered a new take on a type of material known as a one-dimensional photonic crystal. Photonic crystals are made from alternating layers of refractive structures whose arrangement can influence how incoming light is reflected or absorbed.

In 1887, the English physicist John William Strutt, better known as the Lord Rayleigh, established a theory for how light should bend through a similar structure composed of multiple refractive layers. Rayleigh predicted that such a structure could reflect light, but only if that light is coming from a very specific angle. In other words, such a structure could act as a mirror for light shining from a specific direction only.

More than a century later, Joannopoulos and his group found that, in fact, quite the opposite was true. They proved in theoretical terms that, if a one-dimensional photonic crystal were made from layers of materials with certain “refractive indices,” bending light to different degrees, then the crystal as a whole should be able to reflect light coming from any and all directions. Such an arrangement could act as a “perfect mirror.”

The idea was a huge departure from what scientists had long assumed, and as such, when Joannopoulos submitted the research for peer review, it took some time for the journal, and the community, to come around. But he and his students kept at it, ultimately verifying the theory with experiments.

That work led to a high-profile publication, which helped the group focus the idea into a device: Using the principles that they laid out, they effectively fabricated a perfect mirror and folded it into a tube to form a hollow-core fiber. When they shone light through, the inside of the fiber reflected all the light, trapping it entirely in the core as the light pinged through the fiber. In 2000, the team launched a startup to further develop the fiber into a flexible, highly precise and minimally invasive “photonics scalpel,” which has since been used in hundreds of thousands of medical procedures including a surgeries of the brain and spine.

“And get this: We have estimated more than 500,000 procedures across hospitals in the U.S. and abroad,” Joannopoulos proudly stated, to appreciative applause.

Joannopoulos is the recipient of the 2024-2025 James R. Killian, Jr. Faculty Achievement Award, and is the Francis Wright Davis Professor of Physics and director of the Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies at MIT. In response to an audience member who asked what motivated him in the face of initial skepticism, he replied, “You have to persevere if you believe what you have is correct.”

Immeasurable impact

The Killian Award was established in 1971 to honor MIT’s 10th president, James Killian. Each year, a member of the MIT faculty is honored with the award in recognition of their extraordinary professional accomplishments.

Joannopoulos received his PhD from the University of California at Berkeley in 1974, then immediately joined MIT’s physics faculty. In introducing his lecture, Mary Fuller, professor of literature and chair of the MIT faculty, noted: “If you do the math, you’ll know he just celebrated 50 years at MIT.” Throughout that remarkable tenure, Fuller noted Joannopoulos’ profound impact on generations of MIT students.

“We recognize you as a leader, a visionary scientist, beloved mentor, and a believer in the goodness of people,” Fuller said. “Your legendary impact at MIT and the broader scientific community is immeasurable.”

Bending light

In his lecture, which he titled “Working at the Speed of Light,” Joannopoulos took the audience through the basic concepts underlying photonic crystals, and the ways in which he and others have shown that these materials can bend and twist incoming light in a controlled way.

As he described it, photonic crystals are “artificial materials” that can be designed to influence the properties of photons in a way that’s similar to how physical features in semiconductors affect the flow of electrons. In the case of semiconductors, such materials have a specific “band gap,” or a range of energies in which electrons cannot exist.

In the 1990s, Joannopoulos and others wondered whether the same effects could be realized for optical materials, to intentionally reflect, or keep out, some kinds of light while letting others through. And even more intriguing: Could a single material be designed such that incoming light pinballs away from certain regions in a material in predesigned paths?

“The answer was a resounding yes,” he said.

Joannopoulos described the excitement within the emerging field by quoting an editor from the journal Nature, who wrote at the time: “If only it were possible to make materials in which electromagnetic waves cannot propagate at certain frequencies, all kinds of almost-magical things would be possible.”

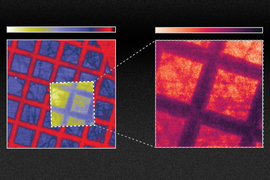

Joannopoulos and his group at MIT began in earnest to elucidate the ways in which light interacts with matter and air. The team worked first with two-dimensional photonic crystals made from a horizontal matrix-like pattern of silicon dots surrounded by air. Silicon has a high refractive index, meaning it can greatly bend or reflect light, while air has a much lower index. Joannopoulos predicted that the silicon could be patterned to ping light away, forcing it to travel through the air in predetermined paths.

In multiple works, he and his students showed through theory and experiments that they could design photonic crystals to, for instance, bend incoming light by 90 degrees and force light to circulate only at the edges of a crystal under an applied magnetic field.

“Over the years there have been quite a few examples we’ve discovered of very anomalous, strange behavior of light that cannot exist in normal objects,” he said.

In 1998, after showing that light can be reflected from all directions from a stacked, one-dimensional photonic crystal, he and his students rolled the crystal structure into a fiber, which they tested in a lab. In a video that Joannopoulos played for the audience, a student carefully aimed the end of the long, flexible fiber at a sheet of material made from the same material as the fiber’s casing. As light pumped through the multilayered photonic lining of the fiber and out the other end, the student used the light to slowly etch a smiley face design in the sheet, drawing laughter from the crowd.

As the video demonstrated, although the light was intense enough to melt the material of the fiber’s coating, it was nevertheless entirely contained within the fiber’s core, thanks to the multilayered design of its photonic lining. What’s more, the light was focused enough to make precise patterns when it shone out of the fiber.

“We had originally developed this [optical fiber] as a military device,” Joannopoulos said. “But then the obvious choice to use it for the civilian population was quite clear.”

“Believing in the goodness of people and what they can do”

He and others co-founded Omniguide in 2000, which has since grown into a medical device company that develops and commercializes minimally invasive surgical tools such as the fiber-based “photonics scalpel.” In illustrating the fiber’s impact, Joannopoulos played a news video, highlighting the fiber’s use in performing precise and effective neurosurgery. The optical scalpel has also been used to perform procedures in larynology, head and neck surgery, and gynecology, along with brain and spinal surgeries.

Omniguide is one of several startups that Joannopoulos has helped found, along with Luminus Devices, Inc., WiTricity Corporation, Typhoon HIL, Inc., and Lightelligence. He is author or co-author of over 750 refereed journal articles, four textbooks, and 126 issued U.S. patents. He has earned numerous recognitions and awards, including his election to the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The Killian Award citation states: “Professor Joannopoulos has been a consistent role model not just in what he does, but in how he does it. … Through all these individuals he has impacted — not to mention their academic descendants — Professor Joannopoulos has had a vast influence on the development of science in recent decades.”

At the end of the talk, Yoel Fink, Joannopoulos’ former student and frequent collaborator, who is now professor of materials science, asked Joannopoulos how, particularly in current times, he has been able to “maintain such a positive and optimistic outlook, of humans and human nature.”

“It’s a matter of believing in the goodness of people and what they can do, what they accomplish, and giving an environment where they’re working in, where they feel extermely comfortable,” Joannopoulos offered. “That includes creating a sense of trust between the faculty and the students, which is key. That helps enormously.”