Researchers from MIT and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have discovered that a class of peptides expressed in pancreatic cancer cells could be a promising target for T-cell therapies and other approaches that attack pancreatic tumors.

Known as cryptic peptides, these molecules are produced from sequences in the genome that were not thought to encode proteins. Such peptides can also be found in some healthy cells, but in this study, the researchers identified about 500 that appear to be found only in pancreatic tumors.

The researchers also showed they could generate T cells targeting those peptides. Those T cells were able to attack pancreatic tumor organoids derived from patient cells, and they significantly slowed down tumor growth in a study of mice.

“Pancreas cancer is one of the most challenging cancers to treat. This study identifies an unexpected vulnerability in pancreas cancer cells that we may be able to exploit therapeutically,” says Tyler Jacks, the David H. Koch Professor of Biology at MIT and a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research.

Jacks and William Freed-Pastor, a physician-scientist in the Hale Family Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, are the senior authors of the study, which appears today in Science. Zackery Ely PhD ’22 and Zachary Kulstad, a former research technician at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Koch Institute, are the lead authors of the paper.

Cryptic peptides

Pancreatic cancer has one of the lowest survival rates of any cancer — about 10 percent of patients survive for five years after their diagnosis.

Most pancreatic cancer patients receive a combination of surgery, radiation treatment, and chemotherapy. Immunotherapy treatments such as checkpoint blockade inhibitors, which are designed to help stimulate the body’s own T cells to attack tumor cells, are usually not effective against pancreatic tumors. However, therapies that deploy T cells engineered to attack tumors have shown promise in clinical trials.

These therapies involve programming the T-cell receptor (TCR) of T cells to recognize a specific peptide, or antigen, found on tumor cells. There are many efforts underway to identify the most effective targets, and researchers have found some promising antigens that consist of mutated proteins that often show up when pancreatic cancer genomes are sequenced.

In the new study, the MIT and Dana-Farber team wanted to extend that search into tissue samples from patients with pancreatic cancer, using immunopeptidomics — a strategy that involves extracting the peptides presented on a cell surface and then identifying the peptides using mass spectrometry.

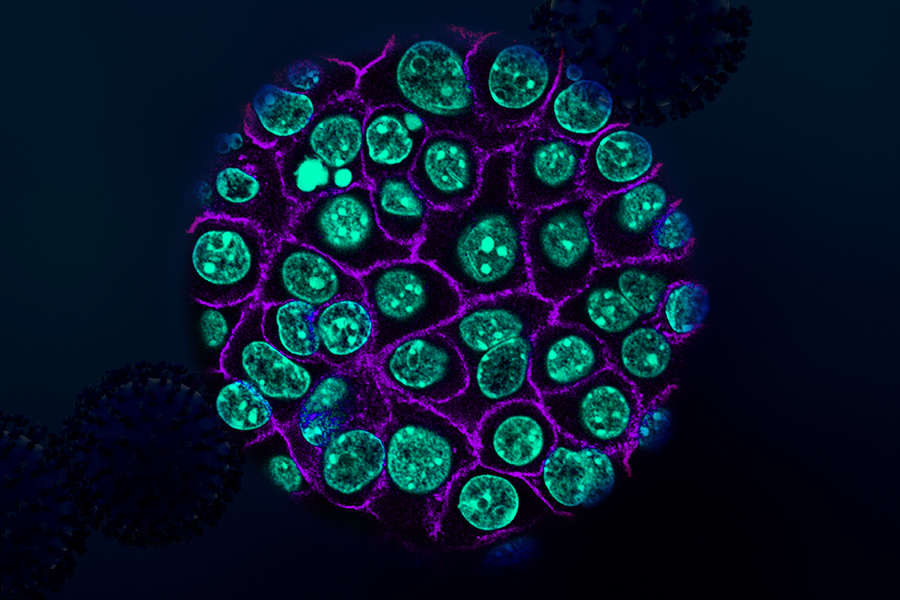

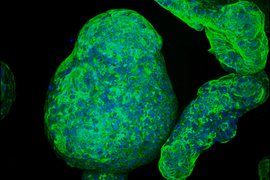

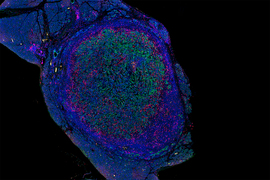

Using tumor samples from about a dozen patients, the researchers created organoids — three-dimensional growths that partially replicate the structure of the pancreas. The immunopeptidomics analysis, which was led by Jennifer Abelin and Steven Carr at the Broad Institute, found that the majority of novel antigens found in the tumor organoids were cryptic antigens. Cryptic peptides have been seen in other types of tumors, but this is the first time they have been found in pancreatic tumors.

Each tumor expressed an average of about 250 cryptic peptides, and in total, the researchers identified about 1,700 cryptic peptides.

“Once we started getting the data back, it just became clear that this was by far the most abundant novel class of antigens, and so that’s what we wound up focusing on,” Ely says.

The researchers then performed an analysis of healthy tissues to see if any of these cryptic peptides were found in normal cells. They found that about two-thirds of them were also found in at least one type of healthy tissue, leaving about 500 that appeared to be restricted to pancreatic cancer cells.

“Those are the ones that we think could be very good targets for future immunotherapies,” Freed-Pastor says.

Programmed T cells

To test whether these antigens might hold potential as targets for T-cell-based treatments, the researchers exposed about 30 of the cancer-specific antigens to immature T cells and found that 12 of them could generate large populations of T cells targeting those antigens.

The researchers then engineered a new population of T cells to express those T-cell receptors. These engineered T cells were able to destroy organoids grown from patient-derived pancreatic tumor cells. Additionally, when the researchers implanted the organoids into mice and then treated them with the engineered T cells, tumor growth was significantly slowed.

This is the first time that anyone has demonstrated the use of T cells targeting cryptic peptides to kill pancreatic tumor cells. Even though the tumors were not completely eradicated, the results are promising, and it is possible that the T-cells’ killing power could be strengthened in future work, the researchers say.

Freed-Pastor’s lab is also beginning to work on a vaccine targeting some of the cryptic antigens, which could help stimulate patients’ T cells to attack tumors expressing those antigens. Such a vaccine could include a collection of the antigens identified in this study, including those frequently found in multiple patients.

This study could also help researchers in designing other types of therapy, such as T cell engagers — antibodies that bind an antigen on one side and T cells on the other, which allows them to redirect any T cell to kill tumor cells.

Any potential vaccine or T cell therapy is likely a few years away from being tested in patients, the researchers say.

The research was funded in part by the Hale Family Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research, the Lustgarten Foundation, Stand Up To Cancer, the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, a Conquer Cancer Young Investigator Award, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Cancer Institute.