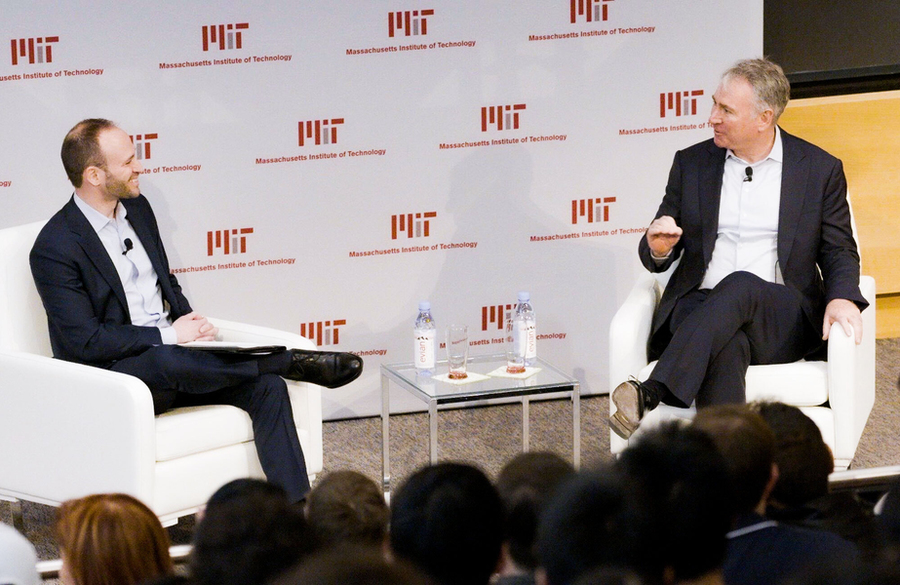

Citadel founder and CEO Ken Griffin had some free advice for an at-capacity crowd of MIT students at the Wong Auditorium during a campus visit in April. “If you find yourself in a career where you’re not learning,” he told them, “it’s time to change jobs. In this world, if you’re not learning, you can find yourself irrelevant in the blink of an eye.”

During a conversation with Bryan Landman ’11, senior quantitative research lead for Citadel’s Global Quantitative Strategies business, Griffin reflected on his career and offered predictions for the impact of technology on the finance sector. Citadel, which he launched in 1990, is now one of the world’s leading investment firms. Griffin also serves as non-executive chair of Citadel Securities, a market maker that is known as a key player in the modernization of markets and market structures.

“We are excited to hear Ken share his perspective on how technology continues to shape the future of finance, including the emerging trends of quantum computing and AI,” said David Schmittlein, the John C Head III Dean and professor of marketing at MIT Sloan School of Management, who kicked off the program. The presentation was jointly sponsored by MIT Sloan, the MIT Schwarzman College of Computing, the School of Engineering, MIT Career Advising and Professional Development, and Citadel Securities Campus Recruiting.

The future, in Griffin’s view, “is all about the application of engineering, software, and mathematics to markets. Successful entrepreneurs are those who have the tools to solve the unsolved problems of that moment in time.” He launched Citadel only one year after graduating from college. “History so far has been kind to the vision I had back in the late ’80s,” he said.

Griffin realized very early in his career “that you could use a personal computer and quantitative finance to price traded securities in a way that was much more advanced than you saw on your typical equity trading desk on Wall Street.” Both businesses, he told the audience, are ultimately driven by research. “That’s where we formulate the ideas, and trading is how we monetize that research.”

It’s also why Citadel and Citadel Securities employ several hundred software engineers. “We have a huge investment today in using modern technology to power our decision-making and trading,” said Griffin.

One example of Citadel’s application of technology and science is the firm’s hiring of a meteorological team to expand the weather analytics expertise within its commodities business. While power supply is relatively easy to map and analyze, predicting demand is much more difficult. Citadel’s weather team feeds forecast data obtained from supercomputers to its traders. “Wind and solar are huge commodities,” Griffin explained, noting that the days with highest demand in the power market are cloudy, cold days with no wind. When you can forecast those days better than the market as a whole, that’s where you can identify opportunities, he added.

Pros and cons of machine learning

Asking about the impact of new technology on their sector, Landman noted that both Citadel and Citadel Securities are already leveraging machine learning. “In the market-making business,” Griffin said, “you see a real application for machine learning because you have so much data to parametrize the models with. But when you get into longer time horizon problems, machine learning starts to break down.”

Griffin noted that the data obtained through machine learning is most helpful for investments with short time horizons, such as in its quantitative strategies business. “In our fundamental equities business,” he said, “machine learning is not as helpful as you would want because the underlying systems are not stationary.”

Griffin was emphatic that “there has been a moment in time where being a really good statistician or really understanding machine-learning models was sufficient to make money. That won’t be the case for much longer.” One of the guiding principles at Citadel, he and Landman agreed, was that machine learning and other methodologies should not be used blindly. Each analyst has to cite the underlying economic theory driving their argument on investment decisions. “If you understand the problem in a different way than people who are just using the statistical models,” he said, “you have a real chance for a competitive advantage.”

ChatGPT and a seismic shift

Asked if ChatGPT will change history, Griffin predicted that the rise of capabilities in large language models will transform a substantial number of white collar jobs. “With open AI for most routine commercial legal documents, ChatGPT will do a better job writing a lease than a young lawyer. This is the first time we are seeing traditionally white-collar jobs at risk due to technology, and that’s a sea change.”

Griffin urged MIT students to work with the smartest people they can find, as he did: “The magic of Citadel has been a testament to the idea that by surrounding yourself with bright, ambitious people, you can accomplish something special. I went to great lengths to hire the brightest people I could find and gave them responsibility and trust early in their careers.”

Even more critical to success is the willingness to advocate for oneself, Griffin said, using Gerald Beeson, Citadel’s chief operating officer, as an example. Beeson, who started as an intern at the firm, “consistently sought more responsibility and had the foresight to train his own successors.” Urging students to take ownership of their careers, Griffin advised: “Make it clear that you’re willing to take on more responsibility, and think about what the roadblocks will be.”

When microphones were handed to the audience, students inquired what changes Griffin would like to see in the hedge fund industry, how Citadel assesses the risk and reward of potential projects, and whether hedge funds should give back to the open source community. Asked about the role that Citadel — and its CEO — should play in “the wider society,” Griffin spoke enthusiastically of his belief in participatory democracy. “We need better people on both sides of the aisle,” he said. “I encourage all my colleagues to be politically active. It’s unfortunate when firms shut down political dialogue; we actually embrace it.”

Closing on an optimistic note, Griffin urged the students in the audience to go after success, declaring, “The world is always awash in challenge and its shortcomings, but no matter what anybody says, you live at the greatest moment in the history of the planet. Make the most of it.”