In early 2020, Covid-19 forced countries across Latin America to take measures to keep children, young people, and adults away from schools. Many countries have declared educational quarantines as part of efforts to stop the pandemic, but more than a year-and-a-half later, governments are already thinking, what is next?

While the pandemic may not be over, three MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI) programs: MIT-Brazil, MIT-Chile, and MIT-Mexico, put together a panel of experts to discuss various solutions, explore opportunities, and learn together.

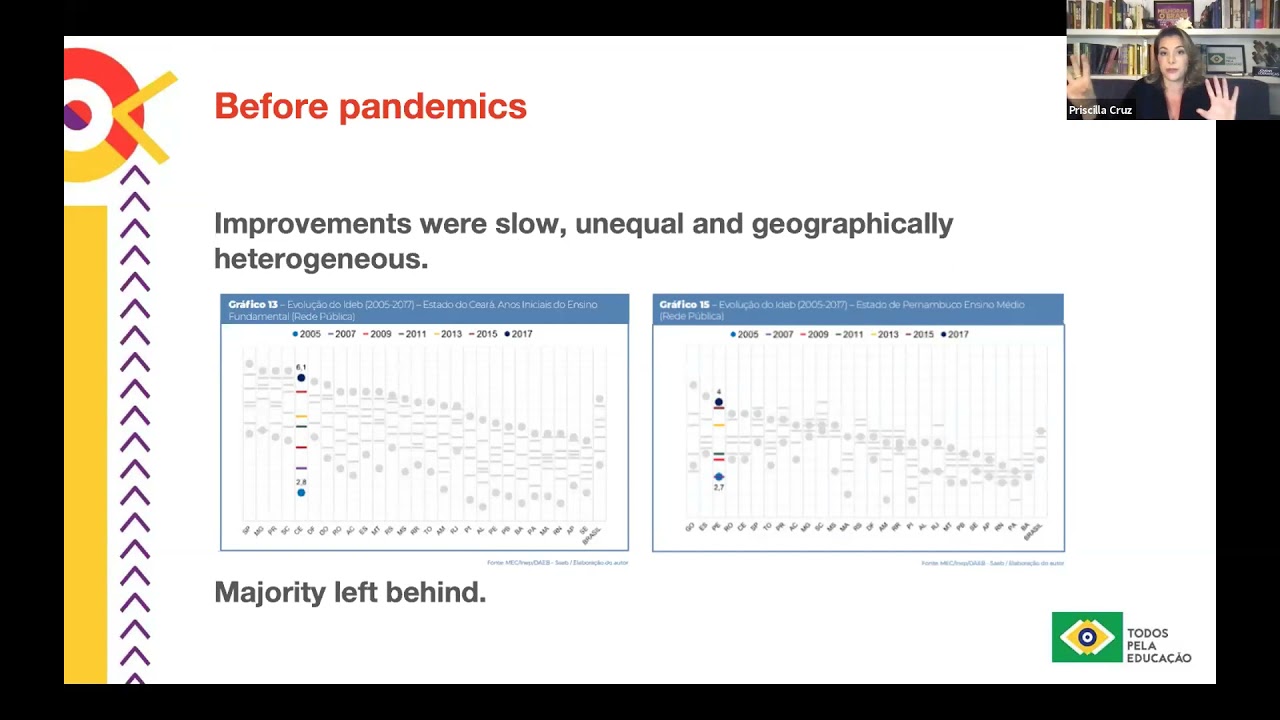

Priscila Cruz, the executive president of Todos Pela Educação, led the conversation around the challenges of basic education within Brazil and Latin America as a whole. Improvements were seen in some states, but not all, and Cruz recognized the “need to universalize equality.”

Cruz explained that while it is still undetermined what the full fallout from the pandemic will be, it is clear that only a few states in Brazil were able to institute remote learning in March 2020. Most schools have not found a sustainable way to continue education. Throughout most of Latin America, it is still unknown what the full future effects of these school closings will be. However, the pandemic has set back recent progress, and it looks like Brazil may be returning to levels of education from 10 years ago.

To move forward, Cruz proposed both short- and long-term solutions, including reform, sharing resources, and implementing best practices from more successful states. More specifically, she also called for a focus on professional development for teachers and increasing technical and vocational courses to help provide the motivation and direction students who have dropped out will need to return to school. "Can we build a new renaissance?" Cruz posed in her conclusion. "It can be or not be an opportunity to build, or we can deep dive into a dark age."

Sylvia Schmelkes, academic vice-chancellor at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico, addressed the themes of education equity, school dropouts, and deficits in learning as aspects to consider when returning to the classrooms regularly after the pandemic ends.

Pre-pandemic education in Mexico was unequally distributed. Schmelkes shared that the past year-and-a-half only added to the inequality, emphasizing layers in disparities such as technological and economic difficulties. Some regions and families have more access to resources, goods, and services, playing a big part in the current situation. Only about 60 percent of the students during this time have been able to follow along with remote classes via television or radio. Between May 2020 and May 2021, poverty levels in Mexico increased from 42 percent to 54 percent of the population — 14.6 million people. As such, the magnitude of the education crisis is enormous.

According to Schmelkes, there are numerous impacts that Covid-19 has had on education not only in Mexico, but across Latin America, from percentages of teachers able to be involved with distance learning to support from educational authorities to increased dropout rates. When considering possible ways forward, Mexico, like Brazil, did not have any schools return to in-person teaching through the 2020-21 academic year. The safety measures put into place will put their own strain on education, from lack of access to running water in rural areas to fewer hours of schooling during the day, making it more challenging to curb long-term effects on education.

Schmelkes recommended possible ways forward based around strategy for ensuring equity, with special attention to areas and communities that had no access to education during this time, a focus on teachers, a re-evaluation of educational assessments, and more.

“This list of ways forward would seem that they are not emergency measures for facing the aftermath of the pandemic, but rather reflect what many of us have always wanted the educational system to be: equitable, inclusive, decentralized, warm and welcoming, centered on significant learning, a system that trusts its teachers and supports them with the training they need to achieve learning results in very diverse realities,” says Schmelkes. “Let’s take advantage of this educational tragedy to profoundly transform our educational systems.”

Paula Louzano, dean, faculty of education at Universidad Diego Portales in Chile, addressed the basic challenges for teachers and educators during this time. In the past couple of decades, Chile focused on the crucial role that teachers play regarding the quality and equity of education by emphasizing the importance of having a well-trained teacher in every classroom. Through policy adjustments, there were efforts to try to attract people to the education profession through improving salaries and working conditions. Like other Latin American countries, Chile saw an increase in demand for teachers as student enrollment increased. However, without national standards or regulations like medical or law professions, this demand was being met with a lower quality of educators.

Louzano highlighted how the pandemic has impacted teachers and educators in two major ways. First, with the transition to online schooling, educator programs were no longer able to have practical training in person. Second, there was a decrease in applications within teacher education programs, while health-related fields saw a spike of interest. Despite the lower status and pay, being able to make a difference in people's lives provided positive value and personal satisfaction. It has become harder for instructors to experience this reward.

In the face of these additional challenges within the education industry, Louzano highlighted some positives to build toward. She emphasized working on the relationships between universities' education programs and the local schools in order to better connect with the needs of the school communities while strengthening the practical segments of the educators' training. "The pandemic is not used as an excuse to lower the quality of our teacher preparation programs, but on the contrary, we use this crisis to become stronger," Louzano expressed.

"Everybody is agreed that you shouldn't let this pandemic go to waste," said moderator Ben Ross Schneider, Ford International Professor of Political Science and faculty director for MIT-Chile. "We have to take advantage of this crisis in order to try and improve the education systems throughout the [Latin American] region."

MISTI is MIT’s pioneering international education program and is part of the Center for International Studies within the Department of Political Science and the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences.