Many forms of Western music make use of harmony, or the sound created by certain pairs of notes. A longstanding question is why some combinations of notes are perceived as pleasant while others sound jarring to the ear. Are the combinations we favor a universal phenomenon? Or are they specific to Western culture?

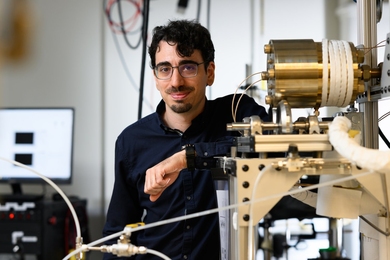

Through intrepid research trips to the remote Bolivian rainforest, researchers in the McDermott lab at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research have found that aspects of the perception of note combinations may be universal, even though the aesthetic evaluation of note combination as pleasant or unpleasant is culture-specific.

“Our work has suggested some universal features of perception that may shape musical behavior around the world,” says MIT associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences Josh McDermott, who is also an associate investigator at the McGovern Institute and senior author of the Nature Communications study. “But it also indicates the rich interplay with cultural influences that give rise to the experience of music.”

Remote learning

Questions about the universality of musical perception are difficult to answer, in part because of the challenge in finding people with little exposure to Western music. McDermott, who is also an investigator in the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines, has found a way to address this problem. His colleagues have performed a series of studies with the participation of an Indigenous population, the Tsimane’, who live in relative isolation from Western culture and have had little exposure to Western music. Accessing the Tsimane’ villages is challenging, as they are scattered throughout the rainforest and only reachable during the dry part of the year.

“When we enter a village there is always a crowd of curious children to greet us,” says Malinda McPherson, a graduate student in the lab and lead author of the study. “Tsimane’ are friendly and welcoming, and we have visited some villages several times, so now many people recognize us.”

In a study published in 2019, McDermott’s team found evidence that the brain’s ability to detect musical octaves is not universal, but is gained through cultural experience. And in 2016 they published findings suggesting that the preference for consonance over dissonance is culture-specific. In their new study, the team decided to explore whether aspects of the perception of consonance and dissonance might nonetheless be universally present across cultures.

Music lessons

In Western music, harmony is the sound of two or more notes heard simultaneously. Think of the Leonard Cohen song, "Hallelujah," where he sings about harmony ("the fourth, the fifth, the minor fall and the major lift"). A combination of two notes is called an interval, and intervals that are perceived to be the most pleasant (or consonant, like the fourth and the fifth, for example) to the Western ear are generally represented by smaller integer ratios.

"Intervals that are related by low integer ratios have fascinated scientists for centuries," McPherson explains. "Such intervals are central to Western music, but are also believed to be a common feature of many musical systems around the world. So intervals are a natural target for cross-cultural research, which can help identify aspects of perception that are and aren’t independent of cultural experience.”

Scientists have been drawn to low integer ratios in music, in part because they relate to the frequencies in voices and many instruments, known as overtones. Overtones from sounds like voices form a particular pattern known as the harmonic series. As it happens, the combination of two concurrent notes related by a low integer ratio partially reproduces this pattern. Because the brain presumably evolved to represent natural sounds, such as voices, it has seemed plausible that intervals with low integer ratios might have special perceptual status across cultures.

Since the Tsimane’ do not generally sing or play music together, meaning they have not been trained to hear or sing in harmony, McPherson and her colleagues were presented with a unique opportunity to explore whether there is anything universal about the perception of musical intervals.

Taking notes

In order to probe the perception of musical intervals, McDermott and colleagues took advantage of the fact that ears accustomed to Western musical harmony often have difficulty picking apart two “consonant” notes when they are played at the same time. This auditory confusion is known as “fusion” in the field. By contrast, two “dissonant” notes are easier to hear as separate.

The tendency of “consonant” notes to be heard by Westerners as fused could reflect their common occurrence in Western music. But it could also be driven by the resemblance of low-integer-ratio note combinations to the harmonic series. This similarity of consonant intervals to the acoustic structure of typical natural sounds raises the possibility that the human brain is biologically tuned to “fuse” consonant notes.

To explore this question, the team ran identical sets of experiments on two participant groups: U.S. non-musicians residing in the Boston metropolitan area and Tsimane’ residing in villages in the Amazon rainforest. Listeners heard two concurrent notes separated by a particular musical interval (consonant or dissonant), and were asked to judge whether they heard one or two sounds. The experiment was performed with both synthetic and natural sounds.

They found that, like the Boston cohort, the Tsimane’ were more likely to mistake two notes as a single sound if they were consonant than if they were dissonant.

“I was surprised by how similar some of the results in Tsimane’ participants were to those in U.S. participants,” says McPherson, “particularly given the striking differences that we consistently see in preferences for musical intervals.”

When it came to whether consonant intervals were more pleasant than dissonant intervals, the results told a very different story. While the U.S. study participants found consonant intervals more pleasant than dissonant intervals, the Tsimane’ showed no preference, implying that our sense of what is pleasant is shaped by culture.

“The fusion results provide an example of a perceptual effect that could influence musical systems, for instance by creating a natural perceptual contrast to exploit,” explains McDermott. “Hopefully our work helps to show how one can conduct rigorous perceptual experiments in the field and learn things that would be hidden if we didn’t consider populations in other parts of the world.”