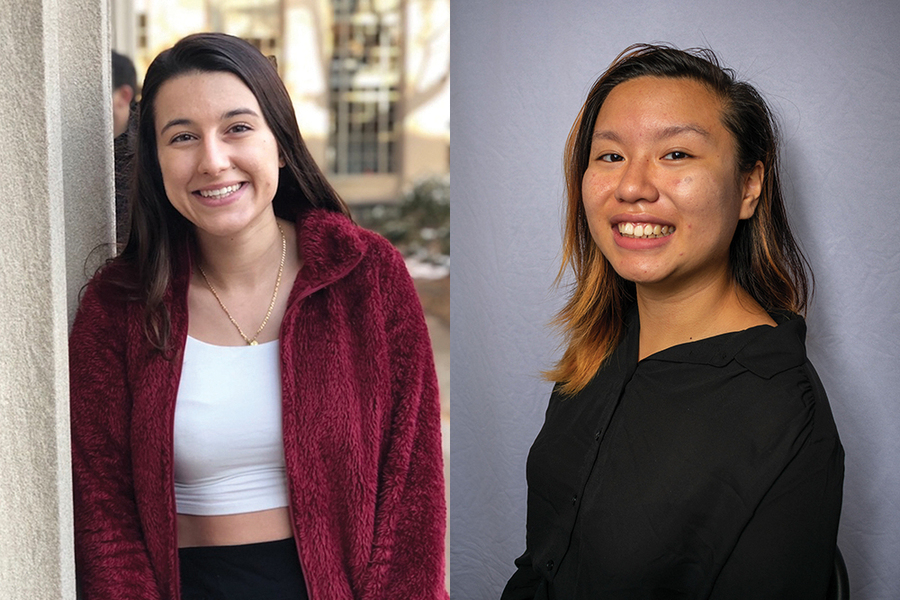

When MIT seniors Therese Mills (mathematics) and Tuyet Pham (electrical engineering and computer science) started working together in late spring 2020, they were just settling into post-pandemic routines. In March, MIT had sent most students home due to Covid-19, and all nonessential faculty and staff were working remotely. Suddenly, the terrain of higher ed looked very different, and the path ahead uncertain. Like many, Mills and Pham wondered what their summer might look like in this new virtual world.

“I think we were all feeling the intensity of the situation,” Mills says. “I personally wanted to do something about it, but something that played to my strong suits. I was searching for internships when I came across a position with the Naval War College, and it seemed like a great opportunity to get involved [in pandemic response], while using math and computer science, my majors.”

The Naval War College (NWC), a longtime partner to the MIT PKG Center for Public Service, was advertising Covid Gaming Solutions positions through the PKG Center’s Social Impact Internship program, which connects undergraduate MIT students to community organizations addressing social and environmental challenges. NWC interns would have the opportunity to use coding, game building, and independent research to explore the complexities of humanitarian aid by creating a simulated response to an imaginary disease outbreak. For Tuyet Pham, the opportunity was equally exciting.

“I’ve always been interested in creating games,” Pham says. “It was also just a fun concept to explore, the butterfly effect [of the pandemic spread]. It seemed like an interesting way to tell people that this situation is really complicated … I think the simulation was a way for me to show how complicated it is to everyone else.”

Through research, collaboration, and coding, Mills and Pham built a simulation that allows users to experience the challenges (and potential triumphs) of responding to the spread of a deadly virus through an imagined community, Olympus. Part Oregon Trail, part Choose Your Own Adventure, the game is a way for those outside of key decision-making stakeholders to understand the complexity and gravity of responding to outbreaks that threaten lives and communities.

“We based a lot of what we did on [an existing game called] Urban Outbreak, which was an in-person version of the simulation, essentially,” Mills explains. “[That game] had different priority-ranking questions, specifically for disaster response. So, in addition to all the research we were doing [on the pandemic and stakeholder organizations], one of our first steps was figuring out how to digitize that experience.”

Wanting the game to be as realistic as possible, Mills and Pham decided to build the simulation from scratch, avoiding existing code and templates that might have limited their options as they got deeper into the game-building process.

“From a technical aspect, it was a huge learning experience,” Mills says. “Tuyet was very ambitious and insisted on starting from nothing, just have a blank file and build from the ground up. I think that was the best decision we could have made. Everything in the game is exactly how we wanted it to be.”

With this level of freedom and control, the pair could prioritize features they found lacking in inspirational counterparts like Urban Outbreak. They didn’t want the game to be too simple, for example, a negative feature they found among Urban Outbreak reviews and one that would undermine the challenge of real-world efforts. They also wanted the game to promote conversation and communication, even if users were playing alone.

“One feature that Tuyet came up with that really helps with the communication part of the simulation is that even though you can play it by yourself, the game itself is constantly giving you feedback as you play,” Mills says. “It’s kind of like a dialogue.”

After months of coding and research, the simulation officially launched on Nov. 24 and is now available for widespread play. “At a time when Covid-19 continues to test and challenge existing humanitarian response frameworks, this online simulation seeks to inform anyone interested in understanding the complexity these conditions present and aims to better prepare future leaders engaged in humanitarian response operations,” NWC officials stated in a recent press release.

Free to use and open to the public, anyone with computer access and Wi-Fi now has the opportunity to confront a virtual pandemic, while living through a literal one.

“To me, this is an important way to explore community issues and disaster relief,” Pham says. “If we’re more aware of the kinds of things that happen behind the scenes, we can start to have more insight into the decisions we see happening around us, more insight into the government and what they’re doing. It’s a way of staying aware of your environment.”