Prominent economist and policymaker Lord Nicholas Stern delivered a strong warning about the dangers of climate change in a talk at MIT on Tuesday, calling the near future “defining” and urging a rapid overhaul of the economy to reach net zero carbon emissions.

“The next 20 years will be absolutely defining,” Stern told the audience, saying they “will shape what kind of future people your age will have.”

“Don’t underestimate the size of the challenge,” Stern added, while giving the MIT Undergraduate Economics Association’s annual public lecture.

To consider the climate trouble we are already in, Stern noted, consider that the concentration of carbon dioxode in the atmosphere is now over 400 parts per million, a level the Earth has not experienced for about 3 million years, long before people were around. (The modern human lineage is estimated to be about 200,000 years old.)

Back then, sea levels were about 30 to 60 feet higher than they are now, Stern said. The recent rise in carbon dioxide concentrations has created rapidly increasing temperatures that could raise the ocean back to those prehuman levels — which would profoundly alter our civilization’s geography.

“It would be Oxford-by-the-Sea,” Stern said, referring to the English university seat that lies about 50 miles inland at present. “Bangladesh would be completely underwater.” Moreover, Stern noted, “Southern Europe would probably look like the Sahara Desert.”

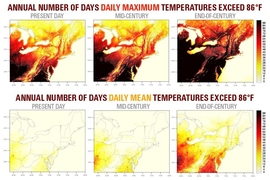

And with a 2 degree Celsius rise in average temperatures, Stern pointed out, the proportion of people on Earth exposed to extreme heat would jump from 14 percent to 37 percent.

“This is the kind of heat that can kill, in a big way,” Stern warned.

“Net zero is fundamental”

As dire as those scenarios seem, Stern also expressed some optimism, saying that policymakers are now much more likely to believe that we can can combine continued economic growth with zero-emissions technology — a change from common views expressed at, say, the 2009 global climate summit in Copenhagen.

“What we’ve seen I think in the last five years or so is a change of understanding of the policy toward climate change,” Stern said, “from ‘How much growth do we have to give up to be more responsible and sustainable?’ to ‘How can we find a form of growth that’s different and sustainable?’”

However, he warned, a world with a net of zero carbon dioxide emissions within a few decades will be absolutely necessary for society to maintain its current form.

“The net zero is fundamental,” Stern said. “That’s not some strange economist’s aspiration. The net zero is the science. If you want to stabilize temperatures, you’re going to have to stabilize concentrations. Stabilizing concentrations means net zero.”

Stern’s lecture, “Unlocking the Inclusive Growth Story of the 21st century: The Drive to the Zero-Carbon Economy,” was delivered to an audience of over 100 people in MIT’s Room 2-190, a lecture hall.

As part of his remarks, Stern contended that the overhaul of energy production and consumption could have leveling economic benefits globally. Indeed, a successful transformation of energy use would almost by definition have a broad impact, he said, since about 70 percent of energy involves infrastructure and 70 percent of growth in coming decades may be located in the developing world.

Multiplying those factors, Stern said, “Half of the story is infrastructure in developing countries and emerging markets.”

Among many specific urban climate measures, Stern suggested that, for instance, “if cities banned internal-combustion engine cars [from] coming into the [city] centers by some date, say, 2025, that would radically change the kinds of cars that come to market.” And he touted the ability of policymakers to effect change, citing the massive global switch to more efficient LED light bulbs as one case where lawmaking has created massive improvements in energy efficiency.

It’s not enough to talk

Stern is an accomplished economist who has studied development and growth extensively, and shifted his focus to include climate economics over the last two decades. He is professor of economics and government and chair of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics.

Stern may be best-known in public for his work as a minister in Britain’s Treasury Department, where he spearheaded a major report on climate and economics, released in 2006. In 2007, Stern was made a life peer in Britain in 2007, and sits in the House of Lords — as a nonpartisan member, he reminded the audience on Tuesday. Stern was chief economist of the World Bank from 2000 to 2003, and president of the British Academy from 2013 to 2017.

As Stern remarked at the beginning of his talk, he also spent a year at MIT in the early 1970s, working with MIT economist Robert M. Solow. Stern said the Institute has “been my U.S. home” through the years.

At one point, Stern asked audience members to raise their hands if they were economists; a significant percentage of people in the room did so.

“Those of you who are not economists,” Stern quipped, “it was your decision, and you have to live with it.”

Stern was introduced at the event by Paul Joskow, the Elizabeth and James Killian Professor of Economics, Emeritus, at MIT, and a faculty member at the Institute for over 45 years. Joskow also led off the question-and-answer session after Stern’s talk with a query about rural land use and its impact on climate. Stern responded that, although he had emphasized urban policy in his talk, rural policies such as reforestation should play a significant role in capturing excess carbon dioxide.

Stern fielded a wide variety of queries, including one about the economics profession from an audience member who asked: “As an economist working on an issue that affects the world in a relatively short time frame, is it enough, is it persuasive enough, to be doing research … and doing presentations like this?”

“No,” Stern responded instantly. “That’s why I spend a lot of time doing other things.” In recent years, Stern has worked with high-level government officials on climate policy matters in China, India, France, and for the U.N., among other projects.

As advice for economics students concerned about climate, Stern suggested: “Invest in your own skill.” And he left no doubt about his own view on the importance of the climate challenge.

“We have the biggest problem facing humankind,” Stern said.