Much of what we hear about public space comes via routine transactional politics, when officials tell us whether or not we can afford, say, parks, schools, and libraries.

But perhaps we should get more input about public space from artists.

That’s one implication of a new book developed by Gediminas Urbonas, an MIT associate professor and artist, which looks at our need for public space as a forum for political expression and basic humane solidarity. In this view, public space is not a luxury to be taken for granted, but is an essential requirement of contemporary life.

“People want lived experiences with other human beings,” Urbonas says. “And we need spaces where we can have shared experience.”

As the book documents, art — public installations, events, architecture, community art projects, and even political demonstrations and theatrical protests — plays a crucial role in shaping our sense of being in a larger community.

Sometimes that art can be directly and explicitly political — something Urbonas thinks we should expect in 2017. He calls the current moment “a time of climate crisis, and perhaps crises of culture and truth.” In other ways, though, art in public spaces simply raises open questions for citizens to grapple with.

“Art teaches us how to disrupt, in order to create a new public space,” Urbonas says. “The point of art is not scaling up answers, but to tackle painful questions, to provoke and mobilize humanity to find the answers themselves, or to create a space of possibility where the truth can be found.”

The book, “Public Space? Lost and Found,” is published by the MIT Press. It is co-edited by Urbonas, who is also director of MIT’s Program in Art, Culture, and Technology (ACT); Ann Lui, an assistant professor at the Art Institute of Chicago; and Lucas Freeman, a writer in residence at ACT. The volume has been named by Metropolis Magazine as one of 25 new architecture and design books to read.

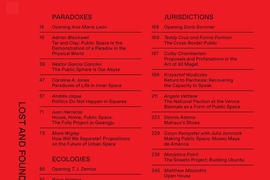

The book is organized into four thematic sections — “Paradoxes,” “Ecologies,” “Jurisdictions,” and “Signals” — featuring diverse types of entries, including essays, case studies, dialogues, and more. There are over 30 contributors to the volume, which was developed after a 2014 MIT conference about public space held in honor of Antoni Montadas, an artist who joined MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) in 1977 and served as professor of the practice at MIT from 1990 through 2014.

Among the volume’s recurring points is the idea that public space, in any form, can never really be politically neutral ground. The creation of physical public space represents political values, for one thing.

For instance, as the Slovenian artist and professor Marjetica Potrc documents in one of the book’s photo-essays, the 2014 creation of Ubuntu Park in Soweto, South Africa, a project she participated in, created a space designed explicitly through a process of community input — by South Africans who had been excluded from public spaces under apartheid.

At the same time, while public space may be designed to be used by anyone, public actions — such as the demonstrations in Tahrir Square, in Egypt — always speak for one group or another in society. Public squares or other such urban spaces are not free from political conflict, but are often claimed for causes. Or, as the writer Adrian Blackwell notes in one essay, “public space is always political and contingent.”

As Urbonas puts it, “The struggle for public space is an ongoing struggle. We cannot ever think that the job is done.”

Another prominent theme of the book is that climate and environmental issues seem likely to loom larger in our conceptions of public space. As Urbonas notes, the private use of natural resources — such as burning fossil fuel — has massive public effects, in the form of, say, intensified hurricanes that do great public damage.

Public art, with this in mind, may well become more adventurous, more quirky, and more often set in nature. The book documents via photos one of Urbonas’ own efforts in this vein, a 2012 project called “River Runs,” on the Thames river in England. As part of the project, people could float downstream on symbolic “jellyfish lily pads,” as a better way of experiencing the value of the ecosystem.

As it happens, thinking about rivers as public space has a significant history at MIT — from a long and ongoing series of Charles River-based events at the Institute, to the “Charles River Project,” a 1970s effort by the noted MIT artist Gyorgy Kepes to think about protecting the Charles River for public use. (Kepes helped found CAVS in 1967.) With this in mind, the “Public Space” book also contains a classic essay by Kepes, “Art and Ecological Consciouness,” in which he decries the idea that nature has “become alien” to us.

“Kepes’ proposition is that art has the power to educate … in a more powerful way than language can,” Urbonas observes. “Art is an amazing form of knowledge, and as it engages materials, it acts directly on people. Kepes’ vision is essential for this time again.”

So the next time you see a public space, it may be fruitful to ask how it was created, how it can be used — and what other kinds of public spaces we should develop as well.

“The point of this book is that we should not be pessimistic and drained by some dystopic scenario,” Urbonas says. “Public space needs to be built, it needs to be created, it needs to be produced. I think this is the optimistic view.”