Audio

As spaceflight becomes more affordable and accessible, the story of human life in space is just beginning. Aurelia Institute wants to make sure that future benefits all of humanity — whether in space or here on Earth.

Founded by Ariel Ekblaw SM ’17, PhD ’20; Danielle DeLatte ’11; and former MIT research scientist Sana Sharma, the nonprofit institute serves as a research lab for space technology and architecture, a center for education and outreach, and a policy hub dedicated to inspiring more people to work in the space industry.

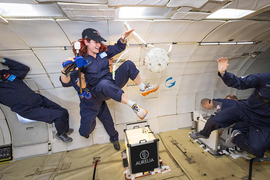

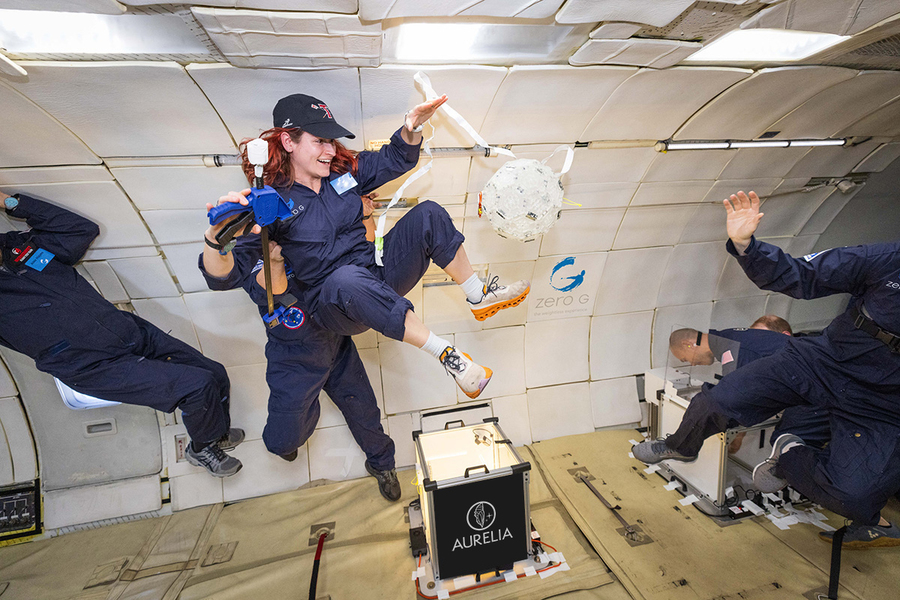

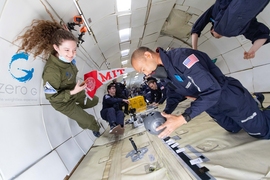

At the heart of the Aurelia Institute’s mission is a commitment to making space accessible to all people. A big part of that work involves annual microgravity flights that Ekblaw says are equal part research missions, workforce training, and inspiration for the next generation of space enthusiasts.

“We’ve done that every year,” Ekblaw says of the flights. “We now have multiple cohorts of students that connect across years. It brings together people from very different backgrounds. We’ve had artists, designers, architects, ethicists, teachers, and others fly with us. In our R&D, we are interested in space infrastructure for the public good. That’s why we’re directing our technology portfolios toward near-term, massive infrastructure projects in low-Earth orbit that benefit life on Earth.”

From the annual flights to the Institute’s self-assembling space architecture technology known as TESSERAE, much of Aurelia’s work is an extension of projects Ekblaw started as a graduate student at MIT.

“My life trajectory changed when I came to MIT,” says Ekblaw, who is still a visiting researcher at MIT. “I am incredibly grateful for the education I got in the Media Lab and the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. MIT is what gave me the skill, the technology, and the community to be able to spin out Aurelia and do something important in the space industry at scale.”

“MIT changes lives”

Ekblaw has always been passionate about space. As an undergraduate at Yale University, she took part in a NASA microgravity flight as part of a research project. In the first year of her PhD program at MIT, she led the launch of the Space Exploration Initiative, a cross-Institute effort to drive innovation at the frontiers of space exploration. The ongoing initiative started as a research group but soon raised enough money to conduct microgravity flights and, more recently, conduct missions to the International Space Station and the moon.

“The Media Lab was like magic in the years I was there,” Ekblaw says. “It had this sense of what we used to call ‘anti-disciplinary permission-lessness.’ You could get funding to explore really different and provocative ideas. Our mission was to democratize access to space.”

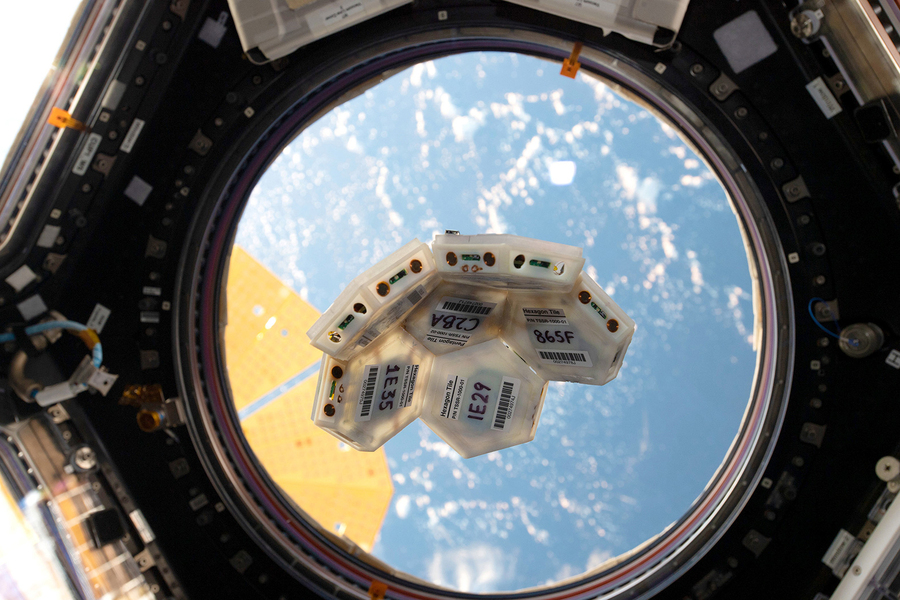

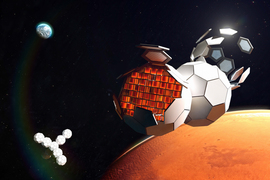

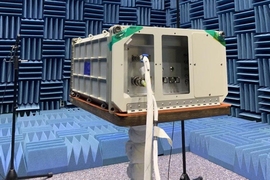

In 2016, while taking a class taught by Neri Oxman, then a professor in the Media Lab, Ekblaw got the idea for the TESSERAE Project, in which tiles autonomously self-assemble into spherical space structures.

“I was thinking about the future of human flight, and the class was a seeding moment for me,” Ekblaw says. “I realized self-assembly works OK on Earth, it works particularly well at small scales like in biology, but it generally struggles with the force of gravity once you get to larger objects. But microgravity in space was a perfect application for self-assembly.”

That semester, Ekblaw was also taking Professor Neil Gershenfeld’s class MAS.863 (How to Make (Almost) Anything), where she began building prototypes. Over the ensuing years of her PhD, subsequent versions of the TESSERAE system were tested on microgravity flights run by the Space Exploration Initiative, in a suborbital mission with the space company Blue Origin, and as part of a 30-day mission aboard the International Space Station.

“MIT changes lives,” Ekblaw says. “It completely changed my life by giving me access to real spaceflight opportunities. The capstone data for my PhD was from an International Space Station mission.”

After earning her PhD in 2020, Ekblaw decided to ask two researchers from the MIT community and the Space Exploration Initiative, Danielle DeLatte and Sana Sharma, to partner with her to further develop research projects, along with conducting space education and policy efforts. That collaboration turned into Aurelia.

“I wanted to scale the work I was doing with the Space Exploration Initiative, where we bring in students, introduce them to zero-g flights, and then some graduate to sub-orbital, and eventually flights to the International Space Station,” Ekblaw says. “What would it look like to bring that out of MIT and bring that opportunity to other students and mid-career people from all walks of life?”

Every year, Aurelia charters a microgravity flight, bringing about 25 people along to conduct 10 to 15 experiments. To date, nearly 200 people have participated in the flights across the Space Exploration Initiative and Aurelia, and more than 70 percent of those fliers have continued to pursue activities in the space industry post-flight.

Aurelia also offers open-source classes on designing research projects for microgravity environments and contributes to several education and community-building activities across academia, industry, and the arts.

In addition to those education efforts, Aurelia has continued testing and improving the TESSERAE system. In 2022, TESSERAE was brought on the first private mission to the International Space Station, where astronauts conducted tests around the system’s autonomous self-assembly, disassembly, and stability. Aurelia will return to the International Space Station in early 2026 for further testing as part of a recent grant from NASA.

The work led Aurelia to recently spin off the TESSERAE project into a separate, for-profit company. Ekblaw expects there to be more spinoffs out of Aurelia in coming years.

Designing for space, and Earth

The self-assembly work is only one project in Aurelia’s portfolio. Others are focused on designing human-scale pavilions and other habitats, including a space garden and a massive, 20-foot dome depicting the interior of space architectures in the future. This space habitat pavilion was recently deployed as part of a six-month exhibit at the Seattle Museum of Flight.

“The architectural work is asking, ‘How are we going to outfit these systems and actually make the habitats part of a life worth living?’” Ekblaw explains.

With all of its work, Aurelia’s team looks at space as a testbed to bring new technologies and ideas back to our own planet.

“When you design something for the rigors of space, you often hit on really robust technologies for Earth,” she says.