The MIT NEW Drug Development ParadIGmS (NEWDIGS) initiative, an international biomedical innovation “think-and-do tank” involving a range of stakeholders in the health care system, hosted a collaborative design lab to advance work on innovative financing models that could make potentially curative — but expensive — therapies accessible to patients and affordable to payers, while ensuring sustainable innovation by industry.

The design lab, held October 18-20 at MIT, was the third in an ongoing NEWDIGS project called Financing and Reimbursement of Cures in the U.S. (FoCUS). Eighty-one people, including senior leaders from a number of biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, as well as patient advocates, public and private payers, clinicians, academic researchers, and venture capitalists, among others, participated.

“The FoCUS program’s goal is not to assess value, but rather to develop innovative approaches to finance value,” said Gigi Hirsch, executive director of the MIT Center for Biomedical Innovation, which runs NEWDIGS. “Our current payment systems were not designed for this. We have to find ways to finance therapies with a high, one time cost up front, whose clinical benefits will accrue over time.”

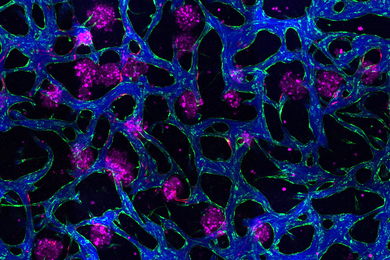

This meeting focused on pressure-testing financing models emerging from past sessions’ work. Case studies included a gene therapy and a portfolio of ultra-orphan products — all currently under development in the industry — and a hypothetical product designed from a blending of characteristics of a group of oncology products. These cases were chosen because they represent classes of innovative therapies that, while suggesting dramatic benefit to patients, may be too expensive to succeed in current financing and reimbursement systems. The project teams are working toward real-world pilots designed to validate the financing models, and gain insights important for scalability.

The NEWDIGS Design Labs are distinguished by their format, which fosters candid dialogue and exploration of issues within a safe haven environment, under the strict terms of case-specific confidentiality agreements as well as the Chatham House Rule. Participants are encouraged to not just identify problems, but also to propose solutions — and cautioned against making assumptions about other stakeholders’ motivations.

“Working together to pressure test solutions is crucial, because we really need to get at stakeholders’ true needs,” said one participant. “We can’t have pilots fail because of knowable but unanticipated constraints on any party’s part.”

“We’re hoping to bring a new medicine to market, but we’re concerned the financing system won’t support it,” said a delegate of the biotech company developing one of the case study medicines. “Payers are scratching their heads, too; no single company can solve it. This week we’re hoping for model recommendations that think through the mechanics and critical decisions from each stakeholder’s point of view.”

“[The FoCUS project] is interesting on several levels,” said a public health expert working for a national patient advocacy organization. “It’s a chance to interact with people with vastly different backgrounds and roles and I think there's a real chance to potentially influence future public policy with some of the outputs of the process.”

Another participant, a program lead in a major pharmaceutical company, underscored the diverse participants’ shared purpose. “I have seen the identification of financing tools based on the willingness of stakeholders to collaborate for the greater good of patients,” she said.

“We’re making great progress in FoCUS, and are developing a design toolkit as we go that everyone can use,” said Hirsch. “In fact, the confidence we have in the project to date has inspired us to take steps toward a new project — Financing of Cures Internationally, or FoCI — so that we can address these challenges on a global scale.”