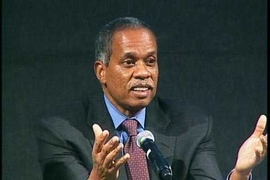

In early March, New York Governor Andrew M. Cuomo announced an ambitious $1.4 billion state plan to revitalize Central Brooklyn — a zone that experiences chronically high rates of unemployment, obesity, and murder. Called “Vital Brooklyn,” the initiative includes a $700 million investment in health care. J. Phillip Thompson, associate professor of urban studies and planning at MIT, was instrumental in shaping this comprehensive approach to health. An urban planner and political scientist who focuses on race, community development, and health, Thompson worked for New York’s Mayor David Dinkins in the early 1990s and has long worked with labor unions and community groups.

Q: How did you become involved in the Vital Brooklyn project?

A: This initiative started in response to a proposal to close the Interfaith Medical Center in Brooklyn in 2015. The hospital workers’ union, Local 1199 (SEIU), and the New York State Nurses Association — along with an array of community organizations, churches, and elected officials — contacted me to put together a community health needs study and to help determine whether it made sense to close that hospital. I think they reached out to me because of my research interests and connection with MIT, and because I’d worked both with Brooklyn community groups and for the New York City government. I think they wanted “experts” they could trust to give them an opinion based on data analysis — who would be straight with them whether the news was good or bad.

Mariana Arcaya, now an assistant professor in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP), and about a dozen students from DUSP also participated in various stages of the research. From analyzing data, speaking with health experts, and surveying the various community groups, we saw that not only was there still a need for a hospital in the community, but that the hospital wasn’t delivering the services that this particular community needed most. For the short term, they needed better cardiovascular and ob/gyn departments. But the larger picture that emerged showed that this was a very sick community. And that most of its illnesses were chronic diseases that can be attributed to poverty and unemployment: asthma caused by mold in substandard housing; obesity due to poor food and fear of going to parks and public spaces for exercise because of violence from the drug trade; and all the ailments that stem from the stress of unemployment.

Q: Can a hospital respond to those conditions?

A: Not on its own. These hospitals all lose money. Typically, when a hospital is losing money, they try to make up the difference by doing things such as performing more heart surgeries, because Medicaid reimburses these surgeries at an advantageous rate. But this makes sense only if you look at each hospital individually. Medicaid is a giant insurance program and the state is the insurer. And it’s not in the state’s interest — or good for its fiscal bottom line — to have more heart surgeries. What’s good for their bottom line is to keep people out of hospitals and out of emergency rooms.

We believe that the only way we can improve community health — and save the state some money — is to build a primary care network throughout the community where people can see a doctor or nurse on a regular basis and get a prescription for medication for high blood pressure or diabetes. It is equally important to aggressively go after the conditions that are responsible for the community’s poor health. We need a comprehensive integrated plan to address social problems. You can’t improve public health unless you consider housing, for example. And you can’t improve housing without looking at unemployment. And you can’t reduce unemployment without looking at the local economy and schools.

It is equally essential that we empower the community to control the process of implementation. That means instead of having contractors and laborers from outside the community build the housing, you hire workers from the community. You establish training and educational support so people can be trained rapidly and become qualified for construction jobs and for work in the community health clinics. We also have to learn to identify underutilized assets in these communities and stop looking at them simply as poor communities. Hospitals and other industries in these communities buy billions of dollars in goods and services from all over the world. Why not have them buy some of them from local vendors? Who does your laundry? Who grows your food? Later, we can start to look at creating more complex local businesses like manufacturing.

Q: And public safety? How does the plan promote that?

A: If you want to solve the problem of fear, of people being afraid of going to the park to exercise, you need to address the issue of felons. This is one of the most difficult issues in the community. What do you do with these people who no one wants to hire? How do you keep them from committing crimes, terrorizing the neighborhood? How do you keep them from returning to prison? In Cleveland, University Hospitals created an industrial laundry, a worker-owned business that deliberately hires ex-felons. This is a way to improve the conditions in communities beset with crime. We believe this idea is replicable in Brooklyn. And we’ve already been contacted on this idea by hospitals in Wilmington, Delaware, and Hartford, Connecticut. Sometimes when you do the right thing, you can improve conditions in a community and save the state money. We believe it’s possible to be fiscally conservative, politically radical, and morally correct, all at the same time.