“An enemy ended my life, took away my bodily strength; then he dipped me in water and drew me out again, and put me in the sun where I soon shed all my hair. The knife’s sharp edge bit into me once my blemishes had been scraped away; fingers folded me and the bird’s feather often moved across my brown surface, sprinkling useful drops….” –Exeter Book, Exeter Cathedral Library, MS 3501

The answer to this medieval riddle is a book, but a contemporary reader unfamiliar with the materials of manuscript production may have difficulty solving it. As Riddle 26 from the Exeter Book outlines, to make a book, you need an animal skin to produce parchment for the pages, a lunellum (a crescent-shaped knife) to prepare the parchment, quills for pens, wood-dye for ink, and gold and leather to adorn and bind the volume. Understanding these material components allows you to solve even greater riddles about who produced the book, who used it, and in the case of music manuscripts, how the medieval world sounded.

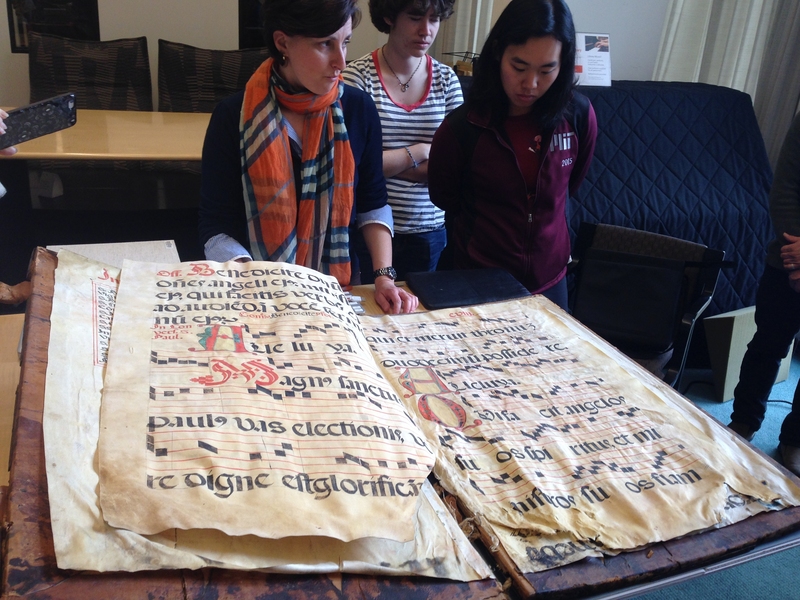

As part of the American Library Association's Preservation Week (April 26 through May 2), MIT's Lewis Music Library hosted “Examining Medieval Chant Manuscripts,” a lecture about the Glaser Codex featuring Michael Cuthbert, the Homer A. Burnell Associate Professor of Music at MIT, and Theresa Zammit Lupi, a book and paper conservator from Rabat, Malta. The event focused on the many insights gleaned from material analysis of such artifacts and how conservation work is indispensable for this area of art historical and musicological research.

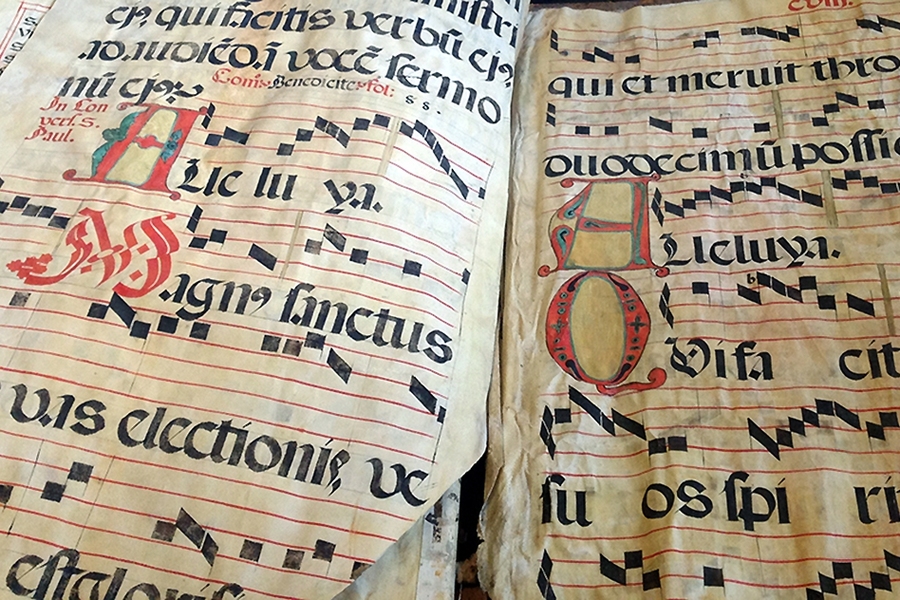

The Glaser Codex at the Lewis Music Library comprises the remains of an approximately 107-folio manuscript of chants for Masses for various saints (a Sanctorale). The script, decorative elements, and goatskin parchment all suggest that the manuscript was produced on the Iberian Peninsula in the 15th century. A scribe in a later hand — probably 16th century — edited the codex, removing some chants, adding others, changing folio numbers, and creating a new index.

The manuscript came to MIT in September 2011, thanks to Constance Kantar. She donated 15 folios, along with the original binding of the manuscript, to MIT in memory of her father Samuel Glaser, who acquired the original. Kantar attended this recent lecture in the Lewis Library and has taken an active interest in obtaining facsimile copies of missing folios for the library.

In their talks, both Cuthbert and Lupi led the audience through an analysis of the material features of the manuscript, as well as the book’s musical notation, before inviting everyone to investigate the folios themselves. Lupi also compared the Glaser folios to the lavishly decorated L’Isle Adam Manuscripts, 10 16th-century Maltese choir books in St. John's Co-Cathedral that were produced in France by followers of printmaker Jean Pichore. Looking at the manuscript’s numerous layers of repairs, which span centuries, she commented that the manuscript “is an archaeological site.”

As with any object-based research, manuscript scholarship is aided significantly by new technologies. Cuthbert points out that contrary to what people may think, medievalists have embraced many technologies, for otherwise their work would be impossible, given the fragmentary state of what comes down to us from the period. Just as we need an intermediary to convert a CD, MP3, or other object into music we can hear and enjoy, “we need specialized tools for translating these manuscript objects into musical sound,” Cuthbert explains. He has developed his own Music21 software to fill in the gaps in fragmentary source material, and also uses musical notation software such as Finale and Sibelius in his classes.

In Fall 2011, the students in 21M.220 (Early Music) were the first to examine the MIT folios of the Glaser Codex, writing about individual pages, helping determine the contents of the manuscript, and raising questions for future research. Cuthbert says that his current students continue to “attempt to reconstruct further this valuable manuscript testimony to the musical and sacred lives of a group of Spaniards from half a millennium ago.” He adds, “We will never solve all the mysteries of the manuscript, but with students in the Early Music class, we are getting closer each year that they study it.”