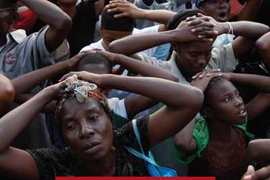

Erica Caple James conducted her dissertation research in trying circumstances: in Haiti, following the 1994 removal of the country’s military leaders. It was a time of social conflict and discord, yet the sense of the anxiety many Haitians felt during their everyday lives was not, to James, an incidental hazard: It was the subject of her work.

Indeed, throughout James’ career as a medical anthropologist, she has specialized in studying people confronted with social, economic, and political uncertainty. James, now an associate professor of anthropology at MIT, has often sought to address a particular question about people placed in such difficulties: Are their psychological and civic needs being addressed by the social organizations that purport to help them?

Or, as James puts it, her work centers on studying “critical junctures at which human life, liberty, and equality are bound or constrained by institutions — whether for good or ill.”

In this vein, James’ field research in Haiti produced an award-winning 2010 book, “Democratic Insecurities,” about the post-1994 reconstruction of the country. Some aid programs, as she documents, helped Haitians recover despite a climate of violence, but other programs reconstituted social divisions or sustained what James calls a “political economy of trauma” in which citizens found financial gain in assuming victim status, and organizations profited from brokering, in James’ term, citizens’ traumas.

Now James, tenured last year, is completing a related book about Haitian immigrants in the U.S. The work examines the role and influence of organized religion, especially the Catholic Church, in assimilating Haitians into the U.S., while detailing the experiences of the aid workers active in the effort.

“The anthropology of humanitarianism is becoming a subdiscipline in and of itself, and I think there is an excitement in asking these kinds of questions,” James says.

Tradition of teaching

James grew up in a family of educators in Milwaukee, where her mother was a teacher and educational administrator and her father was a clinical psychologist; an aunt was the city’s assistant superintendent of schools at one point.

“I was always encouraged to pursue higher education, and my whole family was in education at one time or another,” James says. “Almost everyone on my mom’s side has been a teacher.” Her paternal relatives were equally involved in education: Her grandfather was a professor of agriculture, and her grandmother was a concert pianist and a music professor; even one of James’ great-grandfathers was a professor during Reconstruction in West Virginia.

James says that her own career owes something to both of her parents’ skills: her mother’s commitment to teaching and mentoring students, and her father’s work with people suffering serious problems, including schizophrenia, drug and alcohol abuse, and multiple-personality disorder.

“I look at anthropology as requiring the personal skills to interview people and observe human behavior, and from my father’s side, I have a more specific interest in psychological and psychiatric topics,” James explains. “It was a fascinating environment to grow up in.”

James studied anthropology as an undergraduate at Princeton University. She then acquired a master’s degree at Harvard Divinity School, studying the ecstatic nature of some religious experiences from a psychological perspective, earning her degree in 1995. James also became a licensed physical therapist, going to Haiti to help rehabilitate victims of social and political violence.

Soon James linked these interests together: She entered Harvard University’s PhD program in anthropology, and spent multiple years in Haiti during the period from 1995 to 2000, studying victims of violence. Her therapeutic work helped her gain entry into the society she was studying, in anthropological fashion; her research became the basis of her dissertation. And though few students pursued medical anthropology in the 1990s, she found important intellectual supporters in psychiatrist and anthropologist Arthur Kleinman, her principal advisor, and Paul Farmer, the influential doctor and anthropologist who founded the global medical group Partners in Health.

“My interest in institutional responses to victims of violence grew out of the actual therapeutic work that I participated in with survivors of violence,” James says. “All the types of education I had influenced the kinds of questions I’ve been attuned to.”

In Boston: What happened to Haitians who left?

The innovative, interdisciplinary nature of James’ work has been recognized by other in the field: “Democratic Insecurities” received the 2013 Gordon K. and Sybille Lewis Book Award from the Caribbean Studies Association, as well as an honorable mention for the 2011 Gregory Bateson Book prize from the Society for Cultural Anthropology.

As a follow-up, James’ new book, titled “Wounds of Charity: Haitian Immigrants and Corporate Catholicism in Boston,” is based on the close study of the workers at a Boston-based church center founded to aid immigrants. The center was later incorporated into a network of Catholic social service agencies in Massachusetts. James is studying how both faith and charity shape the immigrants, and also how providing such services shapes the Catholic Church.

“The question I couldn’t answer [in the first project] was, ‘What happened to Haitians who left?’” James says. “That’s why the second project is focused more on Haitian immigrants.”

It is also important, she believes, to study the Catholic Church as an institution at a time when it has been hit hard by abuse scandals.

“The charitable work that Catholic Charities does is being promoted as the brand of the Catholic Church, in some ways helps revamp its image,” James says. “But it does play a longstanding role in providing services to so many people.”

James is also editing a volume of scholarly essays, titled “Faith, Charity, and the Security State,” for the School for Advanced Research Press. For her third book, she plans to study U.S.-based Muslim charities in the period after the terrorist attacks of September 2001, to see how such institutions are assessed by the U.S. government. James has already received the James A. (’45) and Ruth Levitan Prize in the Humanities, an award to fund creative scholarship in the humanities, to help her research on that book progress. It figures to be another chapter in a career spent seeking out tough subjects of study.