The destructive earthquake that hit Haiti in January was only the most recent of the Caribbean nation’s troubles. Years of war, political terror, and dictatorship had left the country in deep disrepair.

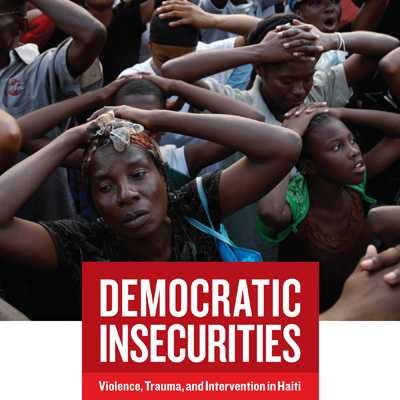

Failed states such as Haiti do not just engender internal strife and violence, however, but can also lead to damaged psyches among their inhabitants, a problem MIT anthropologist Erica James explores in a new book, “Democratic Insecurities: Violence, Trauma, and Intervention,” published by the University of California Press. The psychological toll of political instability, she contends, has never been effectively addressed on a large scale by the outside countries and non-governmental organizations trying to help Haiti.

Indeed, the “paradox” of well-meaning aid, James writes, has been that “many of the efforts to rehabilitate the nation and its citizens, and to promote democracy and economic stability, inadvertently reinforced the practices of predation, corruption and repression that they were intended to repair.” Humanitarian efforts did not end social divisions, but often recreated splits among citizens based on the recent past; dueling organizations of victims of political violence, for instance, squabbled over the legitimacy of members’ claims.

That is a strong claim, but James’ conclusions come from extensive field studies she conducted while also working in Haiti between 1995 and 2000, providing physical therapy to women who had suffered from personal or political acts of violence, including rape. At the time, Haiti was trying to re-establish a viable democracy after decades of dictatorship and, in the early 1990s, a violent coup. “Democratic Insecurities” details the cases of many women James encountered who had spent years living in a condition of severe “ensekerite,” a local term meaning perpetual insecurity. One woman James worked with, Caroline, was repeatedly beaten throughout her life, then later gang raped, an event that caused her husband to leave her and forced Caroline to put her children in the care of a brother; she was perpetually “anxious, depressed and even suicidal,” and had trouble finding work.

Such Haitians needed assistance. But as James sees it, aid programs inadvertently created a “political economy of trauma,” in which citizens competed to assume the role of victims, creating new conflicts and resentments. One rape victim James treated, named Liliane, reintroduced herself to James years later, and gave a public account of having subsequently having been beaten and robbed by a group of men; as James discovered, the second story was false.

These fictions were hardly shocking in Haiti, the most impoverished state of the Western Hemisphere, where annual per-capita income was still just $1,340 per person just before the earthquake, according to the International Monetary Fund. Foreign financial assistance was a desired resource for citizens. But aid programs did not provide a long-term platform for growth in the country. One prominent program, the Human Rights Fund, distributed an average of $15 per week for a family of four. In another case, relatives of Haitians who died in the sinking of a ferry received no more than $125 in compensation.

To be sure, James did witness Haitians who rebuilt their lives thanks to outside aid. Marie, a woman who was gang-raped in 1994, had returned to steady employment by 2000. “Her receipt of assistance from several agencies and agents in the aid apparatus was in no small part integral to her triumph,” James writes in the book.

“Some people received a significant amount of assistance and got back on their feet,” says James. “But there was not a systematic network of institutions that could create sustainable change.”

Getting aid right

Aid groups often need to show tangible signs of progress, such as the quick distribution of aid, which means they can rarely take the time to understand a country’s social needs from the inside.

“There is typically a disconnect between what people are experiencing on the ground and what is perceived at the administrative level,” James says. “There needs to be much more involvement by high-level decision-makers with people in local communities.”

Colleagues applaud James’ ability to link the personal and political in her study. “She’s right at the cutting edge of anthropological studies into conditions of extreme insecurity and political violence, where there is inadequate protection from government and people are vulnerable in failed states,” says Arthur Kleinman, a professor of anthropology at Harvard. “Psychological and psychiatric studies are useful, but she’s also speaking to the broader domain of social policy. We’ve got to address social sources of insecurity and rebuild the fabric of society.”

Specifically, James says, rebuilding Haiti today still requires directing aid dollars to the clinics and organizations on the ground specializing in psychological health. This is a largely missing element, she believes, from the “Action Plan” for reconstruction that the Government of Haiti released at a United Nations conference in March generating support for Haiti’s development. “There is no mention of mental health being a priority right now,” James says. “But there are many people with chronic mental-health issues.” As James acknowledges, it is too soon to pass judgment on post-earthquake relief efforts. She would, however, like aid groups to account for the full range of problems Haitians face, and believes there are “hidden costs” to not focusing more on the psychological needs of the population.

“I don’t see her saying the commitment to aid shouldn’t be given,” adds Kleinman. “But her work should feed into a rethinking of these issues.”

Since the earthquake, James has only been able to speak with just one person she encountered in Haiti in the 1990s. “For most of the people I knew, I’ve had no contact whatsoever,” she says. In the meantime, James is writing a second book, examining how faith-based charities help the Haitian immigrant community integrate itself into American society. And as much as the earthquake has changed the face of Haiti, getting aid right remains vital. “In some ways the world I described in the book no longer exists, but in other ways the issue surrounding aid practices are as important as ever,” James says.

Failed states such as Haiti do not just engender internal strife and violence, however, but can also lead to damaged psyches among their inhabitants, a problem MIT anthropologist Erica James explores in a new book, “Democratic Insecurities: Violence, Trauma, and Intervention,” published by the University of California Press. The psychological toll of political instability, she contends, has never been effectively addressed on a large scale by the outside countries and non-governmental organizations trying to help Haiti.

Indeed, the “paradox” of well-meaning aid, James writes, has been that “many of the efforts to rehabilitate the nation and its citizens, and to promote democracy and economic stability, inadvertently reinforced the practices of predation, corruption and repression that they were intended to repair.” Humanitarian efforts did not end social divisions, but often recreated splits among citizens based on the recent past; dueling organizations of victims of political violence, for instance, squabbled over the legitimacy of members’ claims.

That is a strong claim, but James’ conclusions come from extensive field studies she conducted while also working in Haiti between 1995 and 2000, providing physical therapy to women who had suffered from personal or political acts of violence, including rape. At the time, Haiti was trying to re-establish a viable democracy after decades of dictatorship and, in the early 1990s, a violent coup. “Democratic Insecurities” details the cases of many women James encountered who had spent years living in a condition of severe “ensekerite,” a local term meaning perpetual insecurity. One woman James worked with, Caroline, was repeatedly beaten throughout her life, then later gang raped, an event that caused her husband to leave her and forced Caroline to put her children in the care of a brother; she was perpetually “anxious, depressed and even suicidal,” and had trouble finding work.

Such Haitians needed assistance. But as James sees it, aid programs inadvertently created a “political economy of trauma,” in which citizens competed to assume the role of victims, creating new conflicts and resentments. One rape victim James treated, named Liliane, reintroduced herself to James years later, and gave a public account of having subsequently having been beaten and robbed by a group of men; as James discovered, the second story was false.

These fictions were hardly shocking in Haiti, the most impoverished state of the Western Hemisphere, where annual per-capita income was still just $1,340 per person just before the earthquake, according to the International Monetary Fund. Foreign financial assistance was a desired resource for citizens. But aid programs did not provide a long-term platform for growth in the country. One prominent program, the Human Rights Fund, distributed an average of $15 per week for a family of four. In another case, relatives of Haitians who died in the sinking of a ferry received no more than $125 in compensation.

To be sure, James did witness Haitians who rebuilt their lives thanks to outside aid. Marie, a woman who was gang-raped in 1994, had returned to steady employment by 2000. “Her receipt of assistance from several agencies and agents in the aid apparatus was in no small part integral to her triumph,” James writes in the book.

“Some people received a significant amount of assistance and got back on their feet,” says James. “But there was not a systematic network of institutions that could create sustainable change.”

Getting aid right

Aid groups often need to show tangible signs of progress, such as the quick distribution of aid, which means they can rarely take the time to understand a country’s social needs from the inside.

“There is typically a disconnect between what people are experiencing on the ground and what is perceived at the administrative level,” James says. “There needs to be much more involvement by high-level decision-makers with people in local communities.”

Colleagues applaud James’ ability to link the personal and political in her study. “She’s right at the cutting edge of anthropological studies into conditions of extreme insecurity and political violence, where there is inadequate protection from government and people are vulnerable in failed states,” says Arthur Kleinman, a professor of anthropology at Harvard. “Psychological and psychiatric studies are useful, but she’s also speaking to the broader domain of social policy. We’ve got to address social sources of insecurity and rebuild the fabric of society.”

Specifically, James says, rebuilding Haiti today still requires directing aid dollars to the clinics and organizations on the ground specializing in psychological health. This is a largely missing element, she believes, from the “Action Plan” for reconstruction that the Government of Haiti released at a United Nations conference in March generating support for Haiti’s development. “There is no mention of mental health being a priority right now,” James says. “But there are many people with chronic mental-health issues.” As James acknowledges, it is too soon to pass judgment on post-earthquake relief efforts. She would, however, like aid groups to account for the full range of problems Haitians face, and believes there are “hidden costs” to not focusing more on the psychological needs of the population.

“I don’t see her saying the commitment to aid shouldn’t be given,” adds Kleinman. “But her work should feed into a rethinking of these issues.”

Since the earthquake, James has only been able to speak with just one person she encountered in Haiti in the 1990s. “For most of the people I knew, I’ve had no contact whatsoever,” she says. In the meantime, James is writing a second book, examining how faith-based charities help the Haitian immigrant community integrate itself into American society. And as much as the earthquake has changed the face of Haiti, getting aid right remains vital. “In some ways the world I described in the book no longer exists, but in other ways the issue surrounding aid practices are as important as ever,” James says.