The annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), one of the world’s leading gatherings of scientists and researchers, took place Feb. 14-18 at Boston’s Hynes Convention Center. The gathering highlighted a diverse roster of MIT researchers presenting work on everything from human-robot interactions to the convergence of biology and engineering, as well as hands-on demonstrations ranging from tiny model rockets to Lego models of chemical reactions in the atmosphere.

Nearly 10,000 scientists and citizens registered for the conference, including more than 900 journalists from around the world. MIT was represented by about a dozen faculty members and other speakers who presented talks on their research, as well as by students and staffers who engaged in demonstrations at the event’s Family Science Days.

In the dark

Samuel Ting, the Thomas P. Cabot Professor of Physics, summarized 18 years of work to develop a $1.5 billion set of instruments for the International Space Station. Some in attendance had expected that he might use the occasion to present the long-awaited first results of experiments designed to search for direct signs of dark matter in the universe, but Ting said the research team, which consists of six separate groups, was still finishing its analysis of the data and expected to make an announcement in several weeks.

“Everybody has their own interpretations,” Ting said, noting that one of the six teams “has very different theories” from the others. “Certainly we are not going to publish something if it’s not worthwhile.”

Ting said the experiment has examined about 25 billion “events” — impacts by cosmic rays — to search for differences in the ratio of electrons to their antimatter counterparts, called positrons, and for any differences in emissions from different parts of the sky.

Converging on convergence

In another session, Institute Professor Phillip Sharp said that scientific convergence — the ongoing merger of the life, physical and engineering sciences — represents an important new research model for biomedicine. “Convergence will be the emerging paradigm for how medical research will be conducted in the future,” he said, but added that serious policy challenges that must be resolved in order to realize this potential.

Speaking in the same session, Tyler Jacks, the David H. Koch Professor of Biology and director of MIT’s David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, added that this radically new approach holds the potential to chart a new course in cancer research by revolutionizing the disease’s diagnosis, monitoring and treatment.

On a similar theme, Institute Professor Robert Langer spoke on “Challenges and Opportunities at the Confluence of Biotechnology and Nanomaterials.” He described great progress in recent years in the development and commercialization of biomedical innovations through collaboration with materials scientists and engineers.

Hundreds of families, billions of experiments

On Saturday and Sunday, hundreds of families flocked to the AAAS meeting for Family Science Days, which included a series of talks, exhibits and hands-on activities. There, Angela Belcher, the W.M. Keck Professor of Energy, described her lab’s work to harness the power of biological organisms to create new technologies.

“How many of you have ever done a billion experiments?” she asked a group of parents and children, none of whom raised their hands.

In her lab, Belcher explained, it is now possible to do a billion experiments at once, using a beaker full of viruses to extract elements from water and assemble them into batteries or solar cells. She then demonstrated such a virus-built battery in action — a demonstration that she said she had also shown to President Barack Obama during his 2009 visit to MIT.

Other hands-on activities used Lego blocks to show the molecular structure of DNA; gave children a chance to launch tiny, antacid-powered “rockets” made from paper and empty film canisters; and demonstrated airplane-wing function using a miniature wind tunnel and vapor from dry ice. MIT’s D-Lab, which aims to create technologies for use in developing nations, mounted an exhibit that gave children a chance to try out some D-Lab inventions — including devices for shelling corn and for making charcoal briquettes out of charred agricultural waste.

The human side of science

Other talks at the AAAS conference explored subjects in the social sciences, or at the interface between science, technology and the arts. Michel DeGraff, an associate professor of linguistics, described his analysis of Haitian Creole, which has shown that in many ways its structures are more complex than those of related languages. Felice Frankel, a research scientist at MIT’s Center for Materials Science and Engineering, delivered a lecture in which she showed how diagrams, photographs and other research graphics could be improved through a focus on conveying only the most important information in an image.

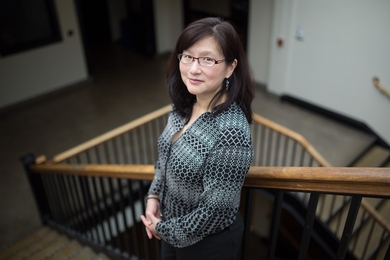

In a keynote address before a packed auditorium, Sherry Turkle, the Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology, described her concern at the growing trend of transferring a variety of human-centered tasks, such as the care of children and the elderly, from human caregivers to robots. People too readily act as if machines have personalities, and even feelings, she said. This “new normal,” she added, “comes with a price,” and may ultimately change human relationships for the worse.

Nearly 10,000 scientists and citizens registered for the conference, including more than 900 journalists from around the world. MIT was represented by about a dozen faculty members and other speakers who presented talks on their research, as well as by students and staffers who engaged in demonstrations at the event’s Family Science Days.

In the dark

Samuel Ting, the Thomas P. Cabot Professor of Physics, summarized 18 years of work to develop a $1.5 billion set of instruments for the International Space Station. Some in attendance had expected that he might use the occasion to present the long-awaited first results of experiments designed to search for direct signs of dark matter in the universe, but Ting said the research team, which consists of six separate groups, was still finishing its analysis of the data and expected to make an announcement in several weeks.

“Everybody has their own interpretations,” Ting said, noting that one of the six teams “has very different theories” from the others. “Certainly we are not going to publish something if it’s not worthwhile.”

Ting said the experiment has examined about 25 billion “events” — impacts by cosmic rays — to search for differences in the ratio of electrons to their antimatter counterparts, called positrons, and for any differences in emissions from different parts of the sky.

Converging on convergence

In another session, Institute Professor Phillip Sharp said that scientific convergence — the ongoing merger of the life, physical and engineering sciences — represents an important new research model for biomedicine. “Convergence will be the emerging paradigm for how medical research will be conducted in the future,” he said, but added that serious policy challenges that must be resolved in order to realize this potential.

Speaking in the same session, Tyler Jacks, the David H. Koch Professor of Biology and director of MIT’s David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, added that this radically new approach holds the potential to chart a new course in cancer research by revolutionizing the disease’s diagnosis, monitoring and treatment.

On a similar theme, Institute Professor Robert Langer spoke on “Challenges and Opportunities at the Confluence of Biotechnology and Nanomaterials.” He described great progress in recent years in the development and commercialization of biomedical innovations through collaboration with materials scientists and engineers.

Hundreds of families, billions of experiments

On Saturday and Sunday, hundreds of families flocked to the AAAS meeting for Family Science Days, which included a series of talks, exhibits and hands-on activities. There, Angela Belcher, the W.M. Keck Professor of Energy, described her lab’s work to harness the power of biological organisms to create new technologies.

“How many of you have ever done a billion experiments?” she asked a group of parents and children, none of whom raised their hands.

In her lab, Belcher explained, it is now possible to do a billion experiments at once, using a beaker full of viruses to extract elements from water and assemble them into batteries or solar cells. She then demonstrated such a virus-built battery in action — a demonstration that she said she had also shown to President Barack Obama during his 2009 visit to MIT.

Other hands-on activities used Lego blocks to show the molecular structure of DNA; gave children a chance to launch tiny, antacid-powered “rockets” made from paper and empty film canisters; and demonstrated airplane-wing function using a miniature wind tunnel and vapor from dry ice. MIT’s D-Lab, which aims to create technologies for use in developing nations, mounted an exhibit that gave children a chance to try out some D-Lab inventions — including devices for shelling corn and for making charcoal briquettes out of charred agricultural waste.

The human side of science

Other talks at the AAAS conference explored subjects in the social sciences, or at the interface between science, technology and the arts. Michel DeGraff, an associate professor of linguistics, described his analysis of Haitian Creole, which has shown that in many ways its structures are more complex than those of related languages. Felice Frankel, a research scientist at MIT’s Center for Materials Science and Engineering, delivered a lecture in which she showed how diagrams, photographs and other research graphics could be improved through a focus on conveying only the most important information in an image.

In a keynote address before a packed auditorium, Sherry Turkle, the Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology, described her concern at the growing trend of transferring a variety of human-centered tasks, such as the care of children and the elderly, from human caregivers to robots. People too readily act as if machines have personalities, and even feelings, she said. This “new normal,” she added, “comes with a price,” and may ultimately change human relationships for the worse.