In keeping with the theme of this year’s student-run MIT Energy Conference — “Insight and Innovation in Uncertain Times” — the two-day program highlighted several major innovations, from both MIT and industry, that could make a dent in global greenhouse gas emissions while helping to meet the energy needs of a growing population.

The conference’s opening panel discussion on Saturday featured four cutting-edge innovations now under development in MIT laboratories: an industrial-scale battery system that could help even out the intermittency of many renewable energy sources; a new material that could store solar heat indefinitely until it’s needed; a way for solar and nuclear power systems to store heat underground for long periods; and electronic control systems that could greatly improve the efficiency of solar panels, electric vehicles and light bulbs.

Introducing that panel, MIT President Susan Hockfield said that sustainable energy “represents truly the great challenge of this generation.” The landscape for research in this area continues to undergo dramatic shifts in response to major accidents, she said — such as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and the Fukushima nuclear meltdowns — and changing estimates of our energy reserves, such as a dramatic increase in U.S. natural-gas output as a result of new technology for unleashing shale gas.

Despite all the economic and technical uncertainties we face, “we do have the power to invent the future we need,” Hockfield said. “I know that we can change the game, and invent the future together.”

One of those potential game-changers is a new kind of utility-scale liquid battery being developed by Donald Sadoway, the John F. Elliot Professor of Materials Chemistry, and his team of students and postdocs. “Storage is a key enabler” for intermittent power sources such as wind, solar, tide and wave power, he said. There is no economically viable battery system today for such applications, Sadoway said, but he believes that a practical solution to the problem is now within reach. He has formed a new company to move toward this goal, which has already raised $13 million from the private sector.

Charles Forsberg, the executive director of the MIT Nuclear Fuel Cycle Study, suggested an entirely different kind of energy storage. He emphasized that in the coming years, to make intermittent energy sources feasible, the world will need energy storage on an unprecedented scale. One practical way of achieving that, Forsberg said, is by storing heat rather than electricity — but doing so would require very large systems, because larger storage systems lose heat much more slowly than smaller ones.

Forsberg suggests that excess energy from nuclear plants or large solar-thermal installations could be stored in rock deep underground, then retrieved later to produce power when it is needed. By allowing much greater flexibility, such a system could dramatically extend the usefulness of such power sources, he said.

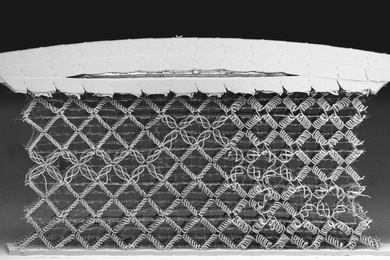

Yet another kind of energy storage was suggested by Jeffrey Grossman, the Carl Richard Soderberg Professor of Power Engineering at MIT. He and his team have found a novel material that can store energy indefinitely by changing the configuration of its molecules. A block of the material could be “charged” by heating it with solar power and then discharged on demand by applying a small input of heat or electricity. For example, a solar cooker using this material could be charged up in the sun during the day, and then used to cook dinner after the sun has set.

Grossman pointed out that in principle, while carbon-based fossil fuels pack a big energy punch in a small package, they are far from the ultimate way of harnessing carbon’s potential: In fact, thin-film solar cells made from graphene could produce 10,000 times more energy from a given amount of carbon, he said.

David Perrault, an MIT professor of electrical engineering, outlined another approach to improving efficiency: new systems that can convert voltages without the losses of conventional transformers. Today, he said, about one-third of all electricity goes through a power-conversion stage — but in the future, virtually all electricity will do so, meaning better power-conversion systems could give a big boost to efficiency. Citing drastic and ongoing improvements in the semiconductor industry, Perrault said, “There is a fundamental opportunity to recreate with energy electronics what has happened over the last 50 years with information electronics.”

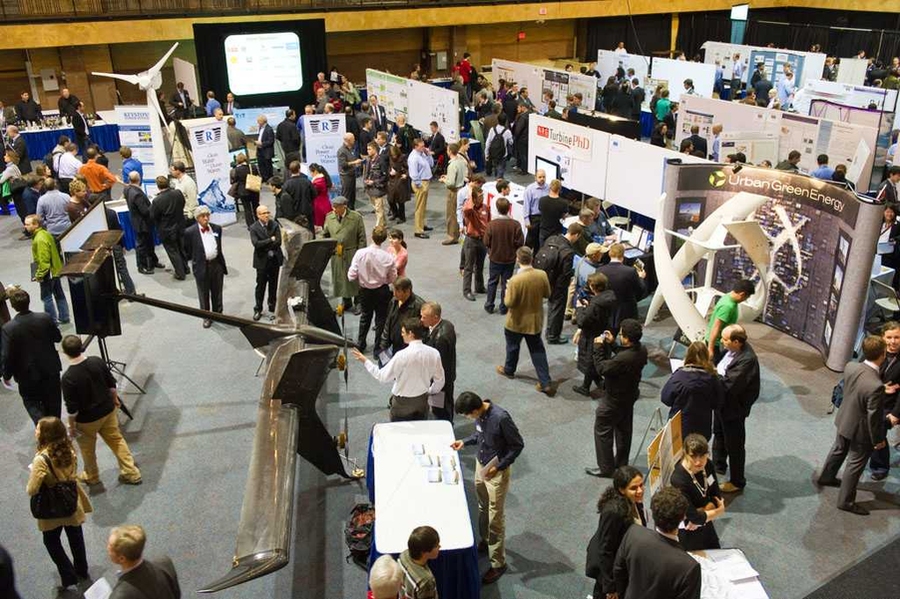

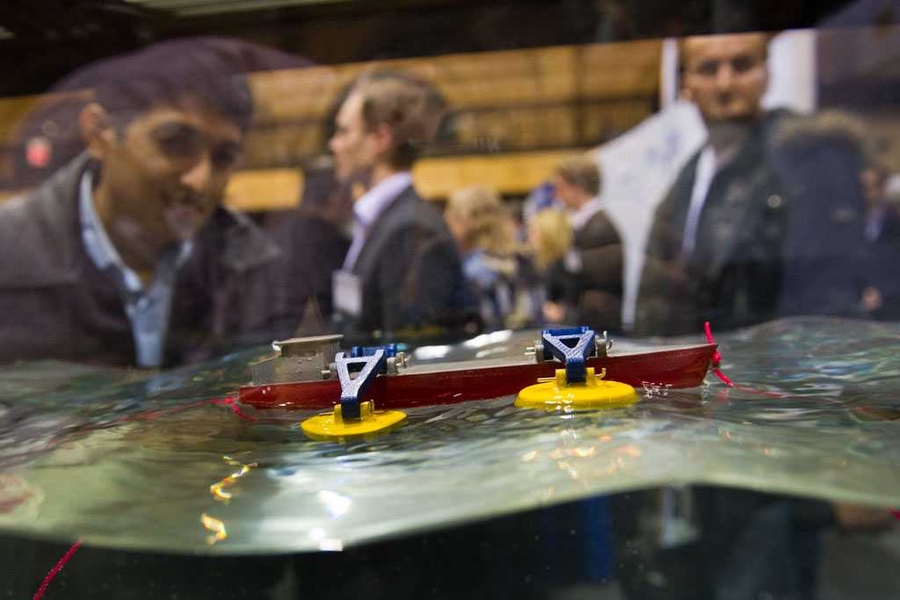

Beyond spotlighting recent advances in MIT research, the Energy Conference also showed off an array of improvements from a variety of companies that displayed their innovations at a showcase exhibit on Friday. These included new systems for generating power from waves or free-flowing rivers; new aerial wind turbines; systems for providing better information and control over individual households’ energy use; and methods for providing heat, hot water and electricity from a single system for off-grid locations.

The conference’s opening panel discussion on Saturday featured four cutting-edge innovations now under development in MIT laboratories: an industrial-scale battery system that could help even out the intermittency of many renewable energy sources; a new material that could store solar heat indefinitely until it’s needed; a way for solar and nuclear power systems to store heat underground for long periods; and electronic control systems that could greatly improve the efficiency of solar panels, electric vehicles and light bulbs.

Introducing that panel, MIT President Susan Hockfield said that sustainable energy “represents truly the great challenge of this generation.” The landscape for research in this area continues to undergo dramatic shifts in response to major accidents, she said — such as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and the Fukushima nuclear meltdowns — and changing estimates of our energy reserves, such as a dramatic increase in U.S. natural-gas output as a result of new technology for unleashing shale gas.

Despite all the economic and technical uncertainties we face, “we do have the power to invent the future we need,” Hockfield said. “I know that we can change the game, and invent the future together.”

One of those potential game-changers is a new kind of utility-scale liquid battery being developed by Donald Sadoway, the John F. Elliot Professor of Materials Chemistry, and his team of students and postdocs. “Storage is a key enabler” for intermittent power sources such as wind, solar, tide and wave power, he said. There is no economically viable battery system today for such applications, Sadoway said, but he believes that a practical solution to the problem is now within reach. He has formed a new company to move toward this goal, which has already raised $13 million from the private sector.

Charles Forsberg, the executive director of the MIT Nuclear Fuel Cycle Study, suggested an entirely different kind of energy storage. He emphasized that in the coming years, to make intermittent energy sources feasible, the world will need energy storage on an unprecedented scale. One practical way of achieving that, Forsberg said, is by storing heat rather than electricity — but doing so would require very large systems, because larger storage systems lose heat much more slowly than smaller ones.

Forsberg suggests that excess energy from nuclear plants or large solar-thermal installations could be stored in rock deep underground, then retrieved later to produce power when it is needed. By allowing much greater flexibility, such a system could dramatically extend the usefulness of such power sources, he said.

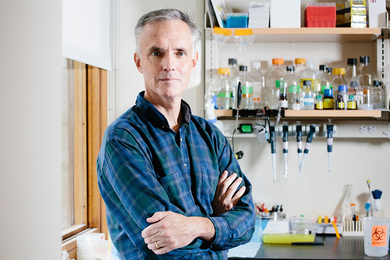

Yet another kind of energy storage was suggested by Jeffrey Grossman, the Carl Richard Soderberg Professor of Power Engineering at MIT. He and his team have found a novel material that can store energy indefinitely by changing the configuration of its molecules. A block of the material could be “charged” by heating it with solar power and then discharged on demand by applying a small input of heat or electricity. For example, a solar cooker using this material could be charged up in the sun during the day, and then used to cook dinner after the sun has set.

Grossman pointed out that in principle, while carbon-based fossil fuels pack a big energy punch in a small package, they are far from the ultimate way of harnessing carbon’s potential: In fact, thin-film solar cells made from graphene could produce 10,000 times more energy from a given amount of carbon, he said.

David Perrault, an MIT professor of electrical engineering, outlined another approach to improving efficiency: new systems that can convert voltages without the losses of conventional transformers. Today, he said, about one-third of all electricity goes through a power-conversion stage — but in the future, virtually all electricity will do so, meaning better power-conversion systems could give a big boost to efficiency. Citing drastic and ongoing improvements in the semiconductor industry, Perrault said, “There is a fundamental opportunity to recreate with energy electronics what has happened over the last 50 years with information electronics.”

Beyond spotlighting recent advances in MIT research, the Energy Conference also showed off an array of improvements from a variety of companies that displayed their innovations at a showcase exhibit on Friday. These included new systems for generating power from waves or free-flowing rivers; new aerial wind turbines; systems for providing better information and control over individual households’ energy use; and methods for providing heat, hot water and electricity from a single system for off-grid locations.