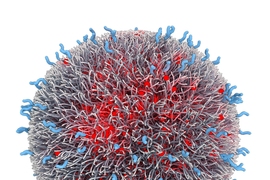

The nanoparticles feature a homing molecule that allows them to specifically attack cancer cells, and are the first such targeted particles to enter human clinical studies. Originally developed by researchers at MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, the particles are designed to carry the chemotherapy drug docetaxel, used to treat lung, prostate and breast cancers, among others.

In the study, which appears April 4 in the journal Science Translational Medicine, the researchers demonstrate the particles’ ability to target a receptor found on cancer cells and accumulate at tumor sites. The particles were also shown to be safe and effective: Many of the patients’ tumors shrank as a result of the treatment, even when they received lower doses than those usually administered.

“The initial clinical results of tumor regression even at low doses of the drug validates our preclinical findings that actively targeted nanoparticles preferentially accumulate in tumors,” says Robert Langer, the David H. Koch Institute Professor in MIT’s Department of Chemical Engineering and a senior author of the paper. “Previous attempts to develop targeted nanoparticles have not successfully translated into human clinical studies because of the inherent difficulty of designing and scaling up a particle capable of targeting tumors, evading the immune system and releasing drugs in a controlled way.”

The Phase I clinical trial was performed by researchers at BIND Biosciences, a company cofounded by Langer and Omid Farokhzad in 2007.

“This study demonstrates for the first time that it is possible to generate medicines with both targeted and programmable properties that can concentrate the therapeutic effect directly at the site of disease, potentially revolutionizing how complex diseases such as cancer are treated,” says Farokhzad, director of the Laboratory of Nanomedicine and Biomaterials at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, associate professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School and a senior author of the paper.

Researchers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Weill Cornell Medical College, TGen Clinical Research Services in Phoenix and the Karmanos Cancer Institute in Detroit were also involved in the study.

Targeted particles

Langer’s lab started working on polymeric nanoparticles in the early 1990s, developing particles made of biodegradable materials. In the early 2000s, Langer and Farokhzad began collaborating to develop methods to actively target the particles to molecules found on cancer cells. By 2006, they had demonstrated that targeted nanoparticles can shrink tumors in mice, paving the road for the eventual development and evaluation of a targeted nanoparticle called BIND-014, which entered clinical trials in January 2011.

For this study, the researchers coated the nanoparticles with targeting molecules that recognize a protein called PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen), found abundantly on the surface of most prostate tumor cells as well as many other types of tumors.

One of the challenges in developing effective drug-delivery nanoparticles, Langer says, is designing them so they can perform two critical functions: evading the body’s normal immune response and reaching their intended targets.

“You need exactly the right combination of these properties, because if they don’t have the right concentration of targeting molecules, they won’t get to the cells you want, and if they don’t have the right stealth properties, they’ll get taken up by macrophages,” says Langer, also a member of the David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT.

The BIND-014 nanoparticles have three components: one that carries the drug, one that targets PSMA, and one that helps evade macrophages and other immune-system cells. A few years ago, Langer and Farokhzad developed a way to manipulate these properties very precisely, creating large collections of diverse particles that could then be tested for the ideal composition.

“They systematically made a set of materials that varied in the properties they thought would matter, and developed a way to screen them. That’s not been done in this kind of setting before,” says Mark Saltzman, a professor of biomedical engineering at Yale University who was not involved in this study. “They’ve taken the concept from the lab into clinical trials, which is quite impressive.”

All of the particles are made of polymers already approved for medical use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Clinical results

The Phase I clinical trial involved 17 patients with advanced or metastatic tumors who had already gone through traditional chemotherapy. In Phase I trials, researchers evaluate a potential drug’s safety and study its effects in the body. To determine safe dosages, patients were given escalating doses of the nanoparticles. So far, doses of BIND-014 have reached the amount of docetaxel usually given without nanoparticles, with no new side effects. The known side effects of docetaxel have also been milder.

In the 48 hours after treatment, the researchers found that docetaxel concentration in the patients’ blood was 100 times higher with the nanoparticles as compared to docetaxel administered in its conventional form. Higher blood concentration of BIND-014 facilitated tumor targeting resulting in tumor shrinkage in patients, in some cases with doses of BIND-014 that correspond to as low as 20 percent of the amount of docetaxel normally given. The nanoparticles were also effective in cancers in which docetaxel usually has little activity, including cervical cancer and cancer of the bile ducts.

The researchers also found that in animals treated with the nanoparticles, the concentration of docetaxel in the tumors was up to tenfold higher than in animals treated with conventional docetaxel injection for the first 24 hours, and that nanoparticle treatment resulted in enhanced tumor reduction.

The Phase I clinical trial is still ongoing and continued dose escalation is underway; BIND Biosciences is now planning Phase II trials, which will further investigate the treatment’s effectiveness in a larger number of patients.

Initial development of the particles at MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, a gift from David H. Koch and the Dana-Farber Harvard Cancer Center Prostate Cancer SPORE. Subsequent development by BIND Biosciences was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and BIND Biosciences.