MIT's Department of Physics is renowned as one of the best in the country. However, it lags behind other schools in its diversity -- a trait the department is determined to change.

Led by department head Edmund Bertschinger, several initiatives are underway to diversify the physics faculty, which now has six women and one underrepresented minority. The figures are higher among the student population, but there is much work to be done, says Bertschinger.

Last month, Bertschinger presented a plan to the physics faculty to draw more women and underrepresented minorities to MIT. Casting a wider net will help the department attract a higher level of academic talent, among both faculty and students, and ensure that MIT maintains its excellence, he says.

"If you restrict the applicant pool for any position, you may be excluding a star candidate," he says. "There are extremely talented underrepresented minorities and women in physics that we can strive to recruit."

Small but growing

Some progress has already been made. Two years ago, the physics department had the smallest percentage of women faculty of any MIT department -- at slightly more than 5 percent. Since then, the department has hired two women and has an offer out to a third, which would bring the total to seven.

Janet Conrad, a particle physicist who arrived at MIT last year from Columbia University, says she's accustomed to being the only woman in a group of physicists, but believes gender-balanced groups are more productive. Throughout her career, she has noticed that as more women join a research group, "women become comfortable in the group. The more women faculty you have, the more you will get."

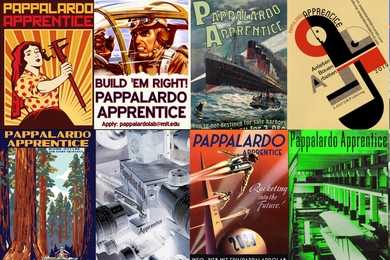

This holds true at MIT: Four of the department's six female faculty members are clustered in the Laboratory for Nuclear Science: Conrad, June Matthews, Gabriella Sciolla and Jocelyn Monroe, a Pappalardo fellow who will become an assistant professor this fall.

Conrad credits Peter Fisher, head of the Particle Physics Division, and Richard Milner, head of the Laboratory for Nuclear Science, for working to make women feel welcome in particle physics.

"There are times when the female postdocs and faculty outnumber the males on the fifth floor (of Building 26)," she says. "One recent evening, the fifth floor was inhabited by all women except for Professor Bruno Coppi. He burst into my office and said, 'Look how MIT has changed! It's marvelous to see this!'"

Part of the recent success stems from a new directive for faculty search committees to come up with lists of star female and minority candidates. The department is also offering funding to bring promising underrepresented candidates to MIT to give talks before they apply, so they can build relationships with faculty here.

Attracting more female graduate students is also a top priority, says Bertschinger. While 30 percent of the department's undergraduate physics majors are women, MIT lags comparable universities in its number of female physics graduate students. As of 2007, only 13.7 percent of MIT's physics graduate students were female, much fewer than at Harvard (37.3 percent), Columbia (35.8 percent) and Caltech (22.8 percent).

Bertschinger wants MIT to start outcompeting those schools for the top women candidates. After female students are admitted, at least one female faculty member contacts each student, and current women graduate students also reach out to each admitted student, inviting them to MIT for dinners and other events.

"Our students -- both undergrad and grad -- are great ambassadors for our program," says Conrad.

The department also recently added a third month of paid maternity leave for graduate students, after students requested the move.

These efforts appear to be having some impact already, as 25 percent of new physics PhD students who entered MIT last fall are female.

Building connections

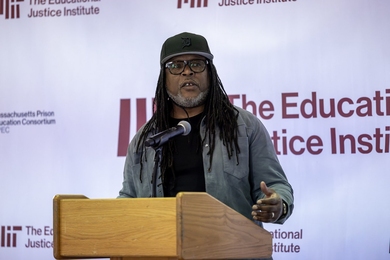

While the numbers of women have been growing, progress has been lagging for minority faculty and graduate students. But several new efforts are underway to boost the number of underrepresented minorities (defined as African Americans, Mexican Americans, Puerto Rican Americans and Native Americans).

In February, the department took its largest-ever contingent to the annual joint conference of the National Society of Black Physicists and National Society of Hispanic Physicists, part of an ongoing effort to recruit more minority graduate students.

Underrepresented minorities make up about 16 percent of MIT's undergraduate physics majors, similar to the Institute's overall percentage of minority undergraduates, but only 3 percent of MIT's physics graduate students are minorities.

One way to elevate those numbers is to build relationships with historically black colleges, in hopes of creating a pipeline of talented physics graduates from those schools to MIT. When such relationships are established, faculty and program directors from those schools will be more likely to encourage their best students to come to MIT, says Tali Figueroa, assistant professor of physics.

"We have to prove to people with good students that their students will have a good experience and come out of MIT even stronger and better than they came in," says Figueroa, a Puerto Rican American who is the department's only minority faculty member.

Bertschinger is also encouraging faculty who travel to large universities to give talks to stay an extra day to give another talk at a nearby black college (for example, faculty visiting the University of Maryland could also give a talk at nearby Morgan State).

The department, in conjunction with the School of Science, is also thinking about setting up a post-baccalaureate program for minority students to spend a year at MIT taking classes and/or doing research before formally applying to graduate school. Such a program would be especially beneficial for students from smaller schools who might be intimidated by the thought of coming to a large research institution such as MIT, says Bertschinger.

Another way to make connections with more minority students is through MIT's MSRP program, which brings minority undergraduates to the Institute every summer to do research (similar to a summer UROP). In recent years the physics department has had few students in the program, but a Florida A&M student who came last year was very successful and plans to apply to MIT for graduate school. At least three physics students plan to attend this summer.

Associate professor of physics Eric Hudson helps to organize MSRP and recently won an MIT Excellence Award in Diversity and Inclusion for that work, as well as for his mentoring of minority physics students and for helping to organize the annual Converge weekend, which brings minority undergraduates to MIT to learn about the Institute before applying to grad school.

Events such as MSRP and Converge can help the entire Institute fulfill its educational mission by drawing talent from the entire population, according to Hudson.

"The goal of MIT is to bring the absolute best people here to work to learn about the world," Hudson says. "If you cut off large groups of people because they don't feel comfortable -- not because they can't do the work -- then you're losing out on an opportunity."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on May 6, 2009 (download PDF).