A team of MIT faculty and researchers including 20 students are working toward what could be the car of the future: a vehicle that drives itself, with people as passengers.

Last week the team tested its vehicle during a site visit by personnel from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which is funding the work through the third DARPA Urban Challenge competition. DARPA will use the site visit evaluation to whittle the current 53 teams to 30 semi-finalists that will compete in a qualifying event in October. At that time all teams will demonstrate their vehicle's ability to navigate through a simple network of roads with other vehicles.

In the final Urban Challenge, set for Nov. 3, the vehicles will execute simulated military supply missions safely in a mock urban area. DARPA will award $2 million, $1 million and $500,000 awards to the top three finishers that complete the course within the six-hour time limit.

Each member of MIT's DARPA team has personal and professional reasons for participating in the Grand Challenge. Edwin Olson, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS), envisions saving the lives of soldiers doing wartime supply runs. Seth Teller, an associate professor in EECS, sees the challenge as a milestone on the way to the eventual elimination of car accidents. And Albert Huang, another EECS Ph.D. student, dreams about the day that he can be driven safely to his parents' house while reading the newspaper.

And an Urban Challenge it will be. The goal is to operate the car safely and autonomously through 60 miles of urban surroundings in less than six hours. The competition will take place at a currently undisclosed location in the western United States.

The team will not know what the course looks like until the day of the event. They will then be given a route network description file with a topological map of the available roads in the course network, and a mission data file with GPS coordinates for checkpoint locations within the network that the car must visit in sequential order.

Checkpoints will be stationary locations that the vehicle can reach only by first completing tasks like merging, passing other vehicles and navigating safely through intersections and traffic circles, all while adhering to speed limits and other traffic laws.

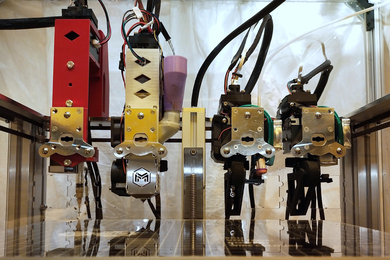

The MIT team's strategy for attacking these problems involves multiple laser range scanners, high-rate video cameras and automotive radar units. The data collected from these sensors is combined into a "local map" of the vehicle's immediate surroundings, including such things as lane markings, stop lines and hazards like potholes and other vehicles. On board there will also be a cluster of up to 40 central processing units that will process the sensor data and perform autonomous planning and motion control.

Among the many challenges the MIT engineers face: This is their first try at the competition. All 10 other "Track A" (funded) teams competing have experience with at least one of the previous DARPA challenges.

John Leonard, associate professor of mechanical and ocean engineering and team leader, does not believe that his team is at a disadvantage because they started from scratch. "We have a fresh perspective and novel ways of thinking that could set us apart, and lead us to new ways of attacking the problem," Leonard said.

He notes the team's unique mixture of backgrounds in mechanical engineering, computer science, aeronautics, and information and decisions systems. The team is organized in three groups: vehicle engineering (including mechanical and electrical systems), led by Associate Professor David Barrett of Olin College; control and planning, led by Jonathan How, MIT associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics; and perception, led by Teller.

Teller sees the team's relative lack of experience as additional motivation for hard work, and is proud of how far they have come already. "They have made amazing advances in such a short time. I would be surprised if other teams have individually discovered all the things we have come up with on our own, in the half year or so that we have been focusing on this effort."

He credits the team with learning how to communicate and divide labor. "The essence of this project is about doing great work, but it is also about learning to work with others from different technical specialties, and eventually communicating our methods to the rest of the world."

Support for MIT's team does not end with the faculty. The Ford-MIT Alliance loaned the team a Land Rover LR3 and paid some of the costs of rewiring it for autonomous operation. Quanta Computer donated two computers for the vehicles that are among the fastest machines in MIT's Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). Institute Professor Thomas Magnanti, dean of the School of Engineering; CSAIL; and MIT's Departments of Aeronautics and Astronautics, EECS and Mechanical Engineering have all contributed significant funds or other resources to the project.

Additional sponsors of Team MIT include The C. S. Draper Laboratory, BAE Systems, MIT Lincoln Laboratory, MIT Information Services and Technology, South Shore Tri-Town Development Corporation, Nokia, and Australia National University.