Audio

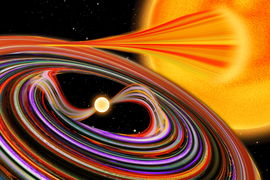

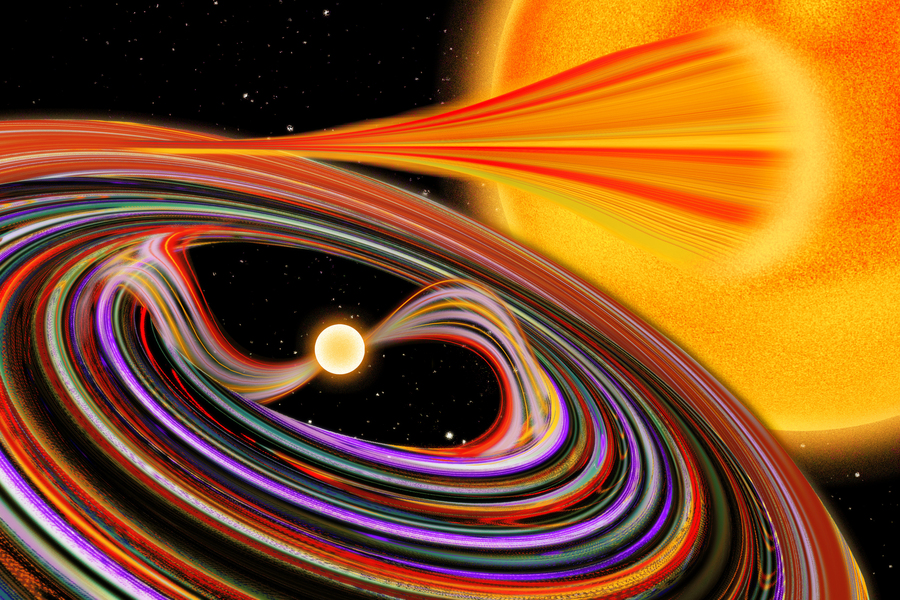

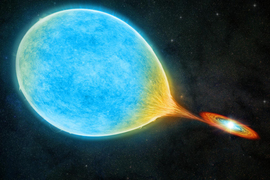

Some 200 light years from Earth, the core of a dead star is circling a larger star in a macabre cosmic dance. The dead star is a type of white dwarf that exerts a powerful magnetic field as it pulls material from the larger star into a swirling, accreting disk. The spiraling pair is what’s known as an “intermediate polar” — a type of star system that gives off a complex pattern of intense radiation, including X-rays, as gas from the larger star falls onto the other one.

Now, MIT astronomers have used an X-ray telescope in space to identify key features in the system’s innermost region — an extremely energetic environment that has been inaccessible to most telescopes until now. In an open-access study published in the Astrophysical Journal, the team reports using NASA’s Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE) to observe the intermediate polar, known as EX Hydrae.

The team found a surprisingly high degree of X-ray polarization, which describes the direction of an X-ray wave’s electric field, as well as an unexpected direction of polarization in the X-rays coming from EX Hydrae. From these measurements, the researchers traced the X-rays back to their source in the system’s innermost region, close to the surface of the white dwarf.

What’s more, they determined that the system’s X-rays were emitted from a column of white-hot material that the white dwarf was pulling in from its companion star. They estimate that this column is about 2,000 miles high — about half the radius of the white dwarf itself and much taller than what physicists had predicted for such a system. They also determined that the X-rays are reflected off the white dwarf’s surface before scattering into space — an effect that physicists suspected but hadn’t confirmed until now.

The team’s results demonstrate that X-ray polarimetry can be an effective way to study extreme stellar environments such as the most energetic regions of an accreting white dwarf.

“We showed that X-ray polarimetry can be used to make detailed measurements of the white dwarf's accretion geometry,” says Sean Gunderson, a postdoc in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, who is the study’s lead author. “It opens the window into the possibility of making similar measurements of other types of accreting white dwarfs that also have never had predicted X-ray polarization signals.”

Gunderson’s MIT Kavli co-authors include graduate student Swati Ravi and research scientists Herman Marshall and David Huenemoerder, along with Dustin Swarm of the University of Iowa, Richard Ignace of East Tennessee State University, Yael Nazé of the University of Liège, and Pragati Pradhan of Embry Riddle Aeronautical University.

A high-energy fountain

All forms of light, including X-rays, are influenced by electric and magnetic fields. Light travels in waves that wiggle, or oscillate, at right angles to the direction in which the light is traveling. External electric and magnetic fields can pull these oscillations in random directions. But when light interacts and bounces off a surface, it can become polarized, meaning that its vibrations tighten up in one direction. Polarized light, then, can be a way for scientists to trace the source of the light and discern some details about the source’s geometry.

The IXPE space observatory is NASA’s first mission designed to study polarized X-rays that are emitted by extreme astrophysical objects. The spacecraft, which launched in 2021, orbits the Earth and records these polarized X-rays. Since launch, it has primarily focused on supernovae, black holes, and neutron stars.

The new MIT study is the first to use IXPE to measure polarized X-rays from an intermediate polar — a smaller system compared to black holes and supernovas, that nevertheless is known to be a strong emitter of X-rays.

“We started talking about how much polarization would be useful to get an idea of what’s happening in these types of systems, which most telescopes see as just a dot in their field of view,” Marshall says.

An intermediate polar gets its name from the strength of the central white dwarf’s magnetic field. When this field is strong, the material from the companion star is directly pulled toward the white dwarf’s magnetic poles. When the field is very weak, the stellar material instead swirls around the dwarf in an accretion disk that eventually deposits matter directly onto the dwarf’s surface.

In the case of an intermediate polar, physicists predict that material should fall in a complex sort of in-between pattern, forming an accretion disk that also gets pulled toward the white dwarf’s poles. The magnetic field should lift the disk of incoming material far upward, like a high-energy fountain, before the stellar debris falls toward the white dwarf’s magnetic poles, at speeds of millions of miles per hour, in what astronomers refer to as an “accretion curtain.” Physicists suspect that this falling material should run up against previously lifted material that is still falling toward the poles, creating a sort of traffic jam of gas. This pile-up of matter forms a column of colliding gas that is tens of millions of degrees Fahrenheit and should emit high-energy X-rays.

An innermost picture

By measuring any polarized X-rays emitted by EX Hydrae, the team aimed to test the picture of intermediate polars that physicists had hypothesized. In January 2025, IXPE took a total of about 600,000 seconds, or about seven days’ worth, of X-ray measurements from the system.

“With every X-ray that comes in from the source, you can measure the polarization direction,” Marshall explains. “You collect a lot of these, and they’re all at different angles and directions which you can average to get a preferred degree and direction of the polarization.”

Their measurements revealed an 8 percent polarization degree that was much higher than what scientists had predicted according to some theoretical models. From there, the researchers were able to confirm that the X-rays were indeed coming from the system’s column, and that this column is about 2,000 miles high.

“If you were able to stand somewhat close to the white dwarf’s pole, you would see a column of gas stretching 2,000 miles into the sky, and then fanning outward,” Gunderson says.

The team also measured the direction of EX Hydrae’s X-ray polarization, which they determined to be perpendicular to the white dwarf’s column of incoming gas. This was a sign that the X-rays emitted by the column were then bouncing off the white dwarf’s surface before traveling into space, and eventually into IXPE’s telescopes.

“The thing that’s helpful about X-ray polarization is that it’s giving you a picture of the innermost, most energetic portion of this entire system,” Ravi says. “When we look through other telescopes, we don’t see any of this detail.”

The team plans to apply X-ray polarization to study other accreting white dwarf systems, which could help scientists get a grasp on much larger cosmic phenomena.

“There comes a point where so much material is falling onto the white dwarf from a companion star that the white dwarf can’t hold it anymore, the whole thing collapses and produces a type of supernova that’s observable throughout the universe, which can be used to figure out the size of the universe,” Marshall offers. “So understanding these white dwarf systems helps scientists understand the sources of those supernovae, and tells you about the ecology of the galaxy.”

This research was supported, in part, by NASA.