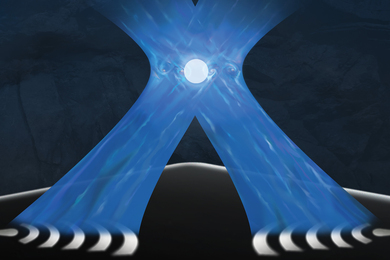

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have found a way to inject into the body a cartilage-laced liquid that, when exposed to light, hardens into cartilage or a kind of "living glue" that connects existing cartilage to bioengineered tissue.

"This substance basically replaces cartilage," said Jennifer Elisseeff, a graduate student in the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences & Technology and lead researcher on the discovery, which has been done on animals and has implications for tissue engineering, plastic and orthopedic surgery and drug delivery in humans. The work was described in the March 1999 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Photopolymerizations -- creating polymer networks in materials in response to light -- are used for bone restorations, filling teeth and for coatings for artificial implants.

This new method potentially could allow physicians to inject a photopolymer material exactly where they want it before shining light on the exterior surface of the skin to turn the viscous liquid solution into a gel. It takes about two minutes of light exposure to polymerize the material injected beneath it.

This noninvasive method of rebuilding damaged or missing cartilage in the nose, ears or joints may make it easier for physicians to do restorative work. Currently, placing self-hardening gels in the body is a tricky business. Physicians must expose the materials to light in "open" environments such as the mouth or during surgery. They must work in a narrow range of temperatures and environments.

By using an injectable system, physicians can precisely place the material while it is still a liquid, and even suck it out and reposition it if necessary.

"This is a method of cartilage tissue engineering that makes it easier to implant a hydrogel" in the body, Elisseeff said. This method could be used to create a variety of new, minimally invasive surgical procedures, or control the release of an encapsulated protein.

Elisseeff has worked on this research for four years with tissue engineering pioneer Robert S. Langer, Germeshausen Professor of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering at MIT.

After hearing plastic surgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital say they would like to have more control over the polymerization reaction, Elisseeff pursued the idea that light could be used to polymerize an implant through the skin.

One of the possible applications of this approach is to use the liquid cartilage as a biological glue to hold bioengineered cartilage in place and integrate it with existing cartilage. Because the liquid includes cells that form living tissue, it is a kind of living glue that can be used to replace or augment damaged knee cartilage, for instance, in patients with osteoarthritis or sports injuries. The hydrogel acts as a scaffold for engineering the growth of cartilage tissue, which will grow to fit the dimensions of the scaffold, Elisseeff said.