Introduction

Stefanie Mueller is an associate professor with a joint appointment in MIT's Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, and Mechanical Engineering departments. Her work is focused on developing novel hardware and software systems that advance personal fabrication technologies. She envisions a world in which anyone can use 3D printing to create any object at any time.

In this episode President Kornbluth talks with Mueller about the future of customizable 3D printing, what it could mean to manufacturing and sustainability, and how to make it accessible to everyone.

Links

Timestamps

Transcript

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Hello, I'm Sally Kornbluth, President of MIT. And I'm thrilled to welcome you to this MIT community podcast, Curiosity Unbounded. Since coming to MIT, I've been particularly inspired by talking with members of our faculty who recently earned tenure. Like their colleagues in every field here, they are pushing the boundaries of knowledge. Their passion and their brilliance, their boundless curiosity offer a wonderful glimpse of the future of MIT.

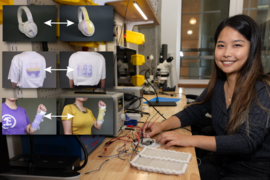

Today, my guest is Stefanie Mueller. Stefanie is an associate professor with dual appointments in electrical engineering and computer science and in mechanical engineering. Stefanie and her group develop novel fabrication techniques that enable everyday objects to sense and interact with their surroundings in new ways. So, Stefanie, welcome to the show.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah, thanks for having me.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: So I want to ask you to break down your work a little bit on novel fabrication techniques that help everyday objects interact with the world in new ways. So what does that exactly mean? And can you give us a few examples?

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah, so our work in novel fabrication techniques allows us to make lots of very interesting novel types of objects. So one example of this is our work on programmable color. So that actually allows everyday objects to change their appearance on demand. In the same way as for instance in digital, you can just use a filter for a photo and it's going to change its appearance, we can do this for physical objects now.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: That is wild. So if I paint my room blue, I can change it to red?

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes, exactly. And we developed a new material for this. And you simply with one click on an app, you can change the appearance of your entire room to match your daily mood. Or if you have an event space, like a restaurant, you can also match with the customer who is hosting an event for that day.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: So I'm not a data scientist. I'm certainly not a physicist. Can you break this down so that our listeners and I can understand how that could possibly happen?

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes. So the smart material is light activated. So as long as you shine some light on it with specific wavelengths, it can go from transparent to any desired color you would like to have. And the light sources we can use are literally any type of light source you can imagine. So it can be just like a flashlight, or it can be a projector to make a specific image. So for the scenario that you described, if you want to change your living room, for instance, to match your daily mood or certain pattern, we can just mount a projector on the ceiling that rotates around, shines some light on the walls, and will reprogram the walls that have the smart material on them.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Amazing. So if you come down in the morning and your spouse has made the house all pitch black, you'll know they might not be in a very good mood.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes, exactly. Yeah, that's a fantastic way to look at it.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Perfect. So how do you build-- it's like a generative AI system, I assume, from the ground up.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: How did you think about this? And how do you formulate this?

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah, so the interesting connection here to generative AI is that generative AI is normally just used for digital items. So you can, for instance, generate an image that's displayed on screen or a 3D model that is displayed on a screen and maybe used in an animation movie. But there's typically not a real outlet for generative AI to extend into the physical space. We actually had a collaboration with a shoe company, where we can now use generative AI to sense the environment you're walking in, and we can reprogram the color of your shoe to match that environment. So let's say if I'm going to--

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Camouflage.

STEFANIE MUELLER: --to camouflage it, or if I go to a after work event, I can have a more colorful shoe.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, very interesting.

STEFANIE MUELLER: If I go to the office, I can have more like a black professional shoe. So depending on the environment I'm in, the app could, for instance, read from my calendar--

SALLY KORNBLUTH: That's crazy.

STEFANIE MUELLER: --where I'm going and what I'm doing.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: That's crazy. It's funny when I think about fabricating things for the environment, I think of Star Trek level, being able to order some food and have it be fabricated. That's obviously science fiction now, but do you see a future like that, where people could just, I need a new shirt, like I could fabricate it in my own home?

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes, I totally see that happen. So when we talk about 3D printing, we always think of just plastics and certain very limited types of materials. But the reality is that computer-driven fabrication expands way beyond just 3D printers. So if you want to have your shirt made at home, there are digital knitting machines, for instance, and weaving machines, where you can just send a pattern and they will knit it for you in any size and shape that you basically want to have. So in the end, it just comes down to where we have everything in one magic machine that can make anything. That's maybe a little far-fetched. Or we have certain devices with specific functionality, like you have a microwave and you have a fridge, but you wouldn't expect that the fridge can also microwave, right?

SALLY KORNBLUTH: That's a good point, yes.

STEFANIE MUELLER: It's not going to happen. So the question is just, what are these core appliances we will have at home that get the most value for customization?

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, I love that. That's great. Are these text prompt systems? In other words, you could see giving a sort of description, I want a blue sweater made of wool. Is that how you see this kind of thing working? And how does it work now with what you can do?

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah so the state of the art actually, right now is still that you have to have some 3D modeling knowledge or some programming knowledge to run these machines. But with generative AI, we will have the ability to basically use these types of text prompts. So my group has done some work for something called large language models, where you can say, I need, for instance, a stand for my iPhone that should look like this beautiful glass mosaic, and it will automatically generate you a stand that will fit your iPhone model, for instance.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: That you would then 3D print?

STEFANIE MUELLER: You would then 3D print that.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Wow. Wow.

STEFANIE MUELLER: And it would have exactly this appearance that you desired without any expert knowledge in 3D modeling or anything.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Wow. It's funny because I was visiting a friend this weekend who does carpentry, and he wanted to build a certain kind of table, so he told ChatGPT in words, I want to build this kind of table, et cetera, and got multiple pictures and picked one, and then ChatGPT generated the instructions for making it by hand.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes, yes, yes.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: So you're talking one step further, not even having to make it.

STEFANIE MUELLER: But even the manual work is very interesting in connection with AI. You always think about this when we teach our students. Right now, they get these manually written out things from the faculty. We give them exercises, like you should do this, and this, and this. But it would be way more interesting to generate something based on the student's individual projects and individual learning challenges that they have, which goes way beyond what the faculty or the teaching assistants can do because there are only so many of them. We can't target, tailor every single student in a perfect around the clock manner. But with these generative AI systems, exactly as you said, they can have these conversations with the generative AI to help them get specific support for their projects.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Yeah, very interesting. So do you see this as a beginning of moving away from mass production? Do you think, if you were to look, I don't know, 20 years down the line, 30 years down the line, do you think that the landscape is going to be very, very different, thinking about how that would scale? And I'm just curious.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah, so I personally think that everything will be personalized in the future.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Interesting.

STEFANIE MUELLER: And if you think way, way far back in time, this is actually how it was when everything was handmade. Right,

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Right, exactly.

STEFANIE MUELLER: You would go to the person making the shoe, and they would customize it for you. But then, obviously, that was only accessible to people who had a lot of money. And with mass manufacturing, now everybody has access to this. I always compare it to the digital domain. In digital, there's nothing standardized anymore. If you go to Google or some other search engine, everything is personalized. Every single website you use is customized to you. And in the physical domain, we still largely use standardized. We can choose, but only from very specific categories. And I think that will go away and will be replaced with personalized items.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: It's interesting because this really parallels, obviously-- I'm a cancer biologist by training. And it really parallels what's going on in medicine and medical treatment, the tension between being able to just mass scale things and the really individually tailored therapeutics that I think will get less expensive and more accessible--

STEFANIE MUELLER: Exactly.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: --with time.

STEFANIE MUELLER: And individually tailored is obviously always better and more desirable.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Yeah, for the individual.

STEFANIE MUELLER: For the individual. Exactly.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Yeah. So if you think about sustainability, how do you think about industry and this sort of mode of manufacturing on our environment and sustainability.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah, so sustainability is a huge challenge. And it is a very complex question to discuss. I think you can look at it from many different angles. I think one interesting angle, in psychology, they have actually shown that if something is made specifically for you, you are actually holding onto the item much longer--

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Interesting.

STEFANIE MUELLER: --than if it's just something you--

SALLY KORNBLUTH: --and taking better care of it.

STEFANIE MUELLER: And taking better care of it because it's really what you wanted. It's very personalized. And maybe you spent some time in personalizing it by going through the interface and so on, which is very different from just clicking something, grabbing something from a rack, and then throwing it out. Fast fashion is especially bad at the moment. Obviously, then there's the other side of it, which is the manufacturing side. How is this going to change the whole mass manufacturing?

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Yes, exactly.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Because obviously, if you can inject 1,000 parts in 1 mold, that's more energy efficient and other things than if you make it personalized for the individual. But it's a very complex question because there's 3D printing and other things. You save assembly. You save storage of parts. You save shipping of parts across the world. So it is a huge, huge topic with many different aspects to it.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, very interesting. It's interesting coming back to the medical applications. We have folks like you here, who work on prosthetics, et cetera. Do you see this as someone can get customized prosthetics? And maybe that's not that far away.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah, so I think medicine is actually one of the early applications for personalization of physical objects. And it can go as far as really making something functional, like a personalized prosthetic that's 3D printed. Those already exist in parts, not the whole prosthetic, but individual segments. But it can be as small as even just helping people with some accessibility needs to get items that work better for them. Sometimes we have one project where we can use these text inputs, where somebody just describes something to customize objects not only with the look, but also with how they feel.

So we just generate it for somebody, they needed a custom walking aid, and they wanted to have something with better grip for their hands. And they could just verbalize, I want it to feel more like rubber. I want to have it more like a rocky surface. I know it's like this part versus this because maybe they couldn't see quite well. And with generative AI, we can not only generate those models visually and the shape, but we can also generate the tactile feel on them.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: On a really common and maybe even somewhat trivial example is I think about right-handed versus left-handed usage. I've met people who are left handed surgeons, for instance, who say their learning curve is longer with standard instruments. Or you think back to third grade, left-handed kids with the right-handed scissors, et cetera. That's a trivial example. But I can imagine--

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes, yes. For sure.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: So how did you actually become interested in 3D printing technology?

STEFANIE MUELLER: So I have a very interesting path of getting to it. A lot of people think 3D printing is a very new technology, maybe 10 years or maybe 20 years old. But the reality is, it was actually invented in the '70s, '80s--

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, really?

STEFANIE MUELLER: --around that time.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: I did not know.

STEFANIE MUELLER: So back then, these were giant machines, a bit like with the first computers. They were also giant machines. Only big companies had access to it. It was very hard to get your fingers on. Everything was closed source. And in the mid 2000's, 2008, around this time, the first low-cost 3D printers came out. And this is when I started my PhD. So I was like oh, now there's actually a way to get your hands on these machines and to tinker with them add some hardware to it, write some code. So I was just there at the right moment in time when this technology became more available.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, interesting.

STEFANIE MUELLER: So in my research field, I was one of the first people who actually developed new ways to use these machines to make new types of objects. And now, they are so widely available. And people have them at home. Every university has them. Libraries have them. Kids in elementary school already know what a 3D printer is.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Yes, yes.

STEFANIE MUELLER: So it's just very interesting how much the technology became available in the last 20 years.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Although I still think it's a little bit daunting for the average person.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes, that's right.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: In other words, so this notion of a ChatGPT-like interface, as opposed to actually having to know how to code or operate the printer. I think there's still a little bit of a gulf there.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes. And that's actually one of the very interesting things with generative AI. It has this potential to lower this entry barrier because you can just describe what you want. But a lot of these generative AI models, they have only been made for on-screen content. So it's actually really funny. If you tell generative AI right now, I want to make a chair, they will generate you the model. But if you actually print it out and you sit on it, it might actually break.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: It will collapse?

STEFANIE MUELLER: It might actually break, yeah, because generative AI is like, look, it looks great. And you're like, OK, but how can I tell you that I actually want to sit on it, it should take this weight, and so on? So generative AI systems, they don't have any notion of this because they are typically trained on images.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, that's interesting. So you're thinking then that these programs are going to have to be supplied with a lot more information on real world use in some way?

STEFANIE MUELLER: Exactly, yeah. And that's actually one of the key focus our lab works on right now is to supply this extra physics-based information. So we have projects both on making sure that things don't break when you actually use them. We actually generated a pair of glasses, and normally they would break in the middle just if they are generated based on images.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, interesting. Yes.

STEFANIE MUELLER: But we feed the generative AI system with some mechanical simulation--

SALLY KORNBLUTH: I see. Interesting.

STEFANIE MUELLER: --so that the simulator can actually say, hey, when you make this shape here, this is too thin. It's going to break. Can you make it a little thicker the next round? And then if you print out those glasses with the 3D printer, now they're actually sturdy. And they won't break the first time you drop them on the floor.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: This has the potential to be huge upheaval in a lot of different industries then.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes, yes, for sure.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: I think about just shopping for glasses and trying to find the right thing. But if you could really tailor it to your own face and pick your colors and--

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes, yes, exactly.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Very interesting.

STEFANIE MUELLER: So I think the whole personalization aspect is huge, again, just also not generating waste by making sure it's really fits you.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Exactly.

STEFANIE MUELLER: I can't even tell you how often I discarded something because after using it for a week or two, I realized, it's not fitting right, or it's uncomfortable.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Yeah, exactly.

STEFANIE MUELLER: If it's really perfectly made for your face, for instance, or for your foot, if you have a shoe, those issues will hopefully not happen.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: That's crazy. Very fun. So I'm wondering about who you would partner with in further development. I don't know how you think about commercialization of all this, but things like safety and fire, police, et cetera, et cetera, things that are bright, things that change colors to reflect sunlight, things that can be cooler or hotter, depending on weather, for people who have to be working outside, et cetera. So how do you think about the partnerships and commercialization that might allow these things to move forward in all these different realms?

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah, so that's very interesting for us because as you said, who's going to be interested in this technology? It's very hard for you to say if you're in research because you're doing the research. But we know very little about what industry exactly needs.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Needs, exactly.

STEFANIE MUELLER: So for me, it's always very helpful when we do a podcast like this, or we have an MIT news article, then actually, a lot of companies see our work, and then they reach out to us.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, really? That's great.

STEFANIE MUELLER: And they're like, hey, we just saw this. Can we have a collaboration on this? Maybe they already have a program with MIT, or they want to create a new collaboration. So we have seen lots of different companies reach out to us. And then all of these interesting questions come up, like, how does the technology survive a whole manufacturing cycle when it's integrated into a specific product? And what are some regulations once you bring it on the road? Once for our color changing technology, we worked with a car company. One of the applications was actually depending on the background. Let's say it's brighter or darker outside, or depending on the background you're driving in, how can we highlight the car so that other people can see you better?

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, that's interesting.

STEFANIE MUELLER: But then what does this mean? What if there's some failure in the technology? The car kind of blends--

SALLY KORNBLUTH: The car becomes invisible, yeah.

STEFANIE MUELLER: --into the environment. So there's lots of different questions related to this.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, that's really good. So you were a student at the Hasso Plattner Institute in Germany. And now you're partnering with them on a project studying sustainable practices, including design solutions to waste reduction. So can you tell us a little bit about that?

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah. So there's this wonderful collaboration with the Hasso Plattner Institute MIT program. It's organized from the Morningside Academy of Design. And what I'm really excited about is that we use generative AI here on a material level. I already talked about using generative AI to maybe ensure that objects don't break and so on. But that's really more on a function level.

So the goal here is, let's say you have recycled material, which, again, comes back to sustainability and waste. Recycled materials are typically not quite as great as new materials because when they get broken down, and let's say, plastics, they get remelted, and let's say they have less structural strength. They can take less weight, for instance. So what we're doing is we are teaching the generative AI model what types of materials are going to be used in manufacturing. And then the generative AI will create a design that can work, even with this slightly weaker material.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, interesting.

STEFANIE MUELLER: So it's still going to be exactly personalized to you, and it's still going to be a desirable design, but it might just look like a little bit different by reshaping certain parts to be more structurally sturdy.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Oh, that's really interesting. So are you glad to be working with colleagues in your native Germany?

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yes, yes, yes. It's nice to speak some German.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Yeah, that's nice. So I'm just wondering how the MIT environment in general enables your work, how you've enjoyed working here, and just sort of a little insight for the audience into the MIT environment.

STEFANIE MUELLER: So MIT is a fantastic environment. And literally, the work I'm doing right now, I can only do because I'm at MIT. And that's just a wonderful thing to say and just to be aware of for myself as well. I traditionally come from a program that was basically computer science only. So we had really, really strong computer science people, and we built really amazing software systems. But just being in this environment, where I have access to mechanical engineers and people working in optics and materials and this whole melting pot of different colleagues ideas, it's really just a fantastic place to be.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: So what do you do when you're not working?

STEFANIE MUELLER: When I'm not working-- so right now, I'm in a very specific stage of my life. I have two small kids. I have a newborn baby and a toddler, so all my--

SALLY KORNBLUTH: I know what you're doing.

STEFANIE MUELLER: --my time and my love goes to taking care of them. Before that, otherwise, I'm a huge activity and travel fan. So I love to do all sorts of sailing and sports. And once the kids are grown up a little bit, I hope to travel again a lot. And that's great, also, if you're faculty. There are so many international programs you can collaborate with. So I look forward to going back to that stage.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Well, eventually, you get back to that stage of life.

STEFANIE MUELLER: I hope so, yeah.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Fantastic. Well, I really enjoyed talking with you and learning a new area that, honestly, I did not know anything about.

STEFANIE MUELLER: Yeah, thanks for having me.

SALLY KORNBLUTH: Very eye opening. And to our audience, thanks again for listening to Curiosity Unbounded. I very much hope you all will join us again. I'm Sally Kornbluth. Stay curious.

Curiosity Unbounded is a production of MIT news and the Institute Office of Communications in partnership with the Office of the President. This episode was researched, written, and produced by Christine Daniloff and Melanie Gonick. Our sound engineer is Dave Lishansky. For show notes, transcripts, and other episodes, please visit news.mit.edu/podcasts/curiosity-unbounded. Please find us on YouTube, Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts. To learn about the latest developments and updates from MIT, please visit news.mit.edu. You can follow us on Facebook and Instagram at CuriosityUnboundedPodcast. Thank you for joining us today.

Tune in next time, when Sally will be speaking with Brent Minchew, an associate professor of geophysics in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences at MIT. Brent's research aims to understand the behavior of glaciers and ice sheets in response to environmental factors. He'll discuss the processes that will drive sea level rise in the coming decades and the potential of interventions to mitigate this impact. We hope you'll be there. And remember, stay curious.