Introduction

Andres Sevtsuk is an associate professor of urban science and planning at MIT. His work focuses on the influence of urban design on travel behavior and quality of life, and contributes to making cities more walkable, sustainable, and equitable.

In this episode President Kornbluth talks with Sevtsuk about the complex forces that shape our cities and the effects of urban planning on sustainable mobility and quality of life for city residents.

Links

Timestamps

Transcript

Sally Kornbluth: Hello, I'm Sally Kornbluth, president of MIT, and I'm thrilled to welcome you to this MIT community podcast, Curiosity Unbounded. One of the greatest pleasures of my job is the opportunity to talk with members of our faculty who recently earned tenure. Like their colleagues in every field here, they're pushing the boundaries of knowledge and possibility. Their passion and brilliance, their boundless curiosity offer a wonderful glimpse of the future of MIT. And this podcast is a way to share that inspiration with the world.

Today my guest is Andres Sevtsuk. Andres is an associate professor in MIT's Department of Urban Studies and Planning. His research focuses on how urban planning can improve the quality of life in cities, including by encouraging people to walk, bike, or ride public transportation.

Andres, welcome to the show.

Andres Sevtsuk: Thank you.

Sally Kornbluth: So your work looks at sustainable mobility in cities. In particular, I know pedestrian traffic flow has been a key focus for you. Your group has developed models of traffic in cities, studied how we can shape urban environments to encourage sustainable ways of getting around. Can you tell us about that work and why it's so important?

Andres Sevtsuk: Yeah. So transportation is one of these areas that is consuming a huge share of urban energy use, about 1/3, and also responsible for about 1/3 of all CO² emissions.

Sally Kornbluth: Mm-hmm.

Andres Sevtsuk: We can really not make a big dent in urban sustainability without tackling transportation. While there's a lot of work going on at MIT and other technical universities on electrifying the vehicle fleet and technology innovations, one of the most powerful things I believe we can do is build cities in a way that naturally makes people want to walk and use transit more. When we do that, we obtain efficiencies that can be an order of magnitude greater than any marginal technology improvement.

As an example, for instance, when you live in a city like Boston that's fairly dense, historic, and provides opportunities for public transit and walking, an average person emits about 2 1/2 tons of carbon from mobility every year. If that similar person lives in Houston, Texas, a city that's a lot more car-oriented, then that average person emits about 9 1/2 tons of carbon per year.

Sally Kornbluth: Wow. Wow. Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: That's about a four-fold difference.

Sally Kornbluth: That's huge.

Andres Sevtsuk: That's purely because of city design.

Sally Kornbluth: Mm-hmm.

Andres Sevtsuk: How the city makes us behave. I'm interested in incentivizing more of that kind of behavior that we get here in Boston.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, and there's also the health benefits, obviously.

Andres Sevtsuk: Absolutely.

Sally Kornbluth: As you were talking about ways to make the cities more pedestrian-friendly, et cetera, I was also thinking about Boston and the terrible parking. In other words, that's one way to incentivize other systems.

Andres Sevtsuk: It is.

Sally Kornbluth: Design a city where the parking is really bad.

Andres Sevtsuk: In fact, I think that's one of the key reasons that incentivized folks to come to MIT by transit, biking and walking, is parking's pretty expensive.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: As it should be.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: It's one of those public goods that oftentimes is under-priced in American cities.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, that's very interesting. So city design then can influence pedestrian traffic. How does pedestrian traffic actually influence how people develop cities and how people plan for what cities are going to look like?

Andres Sevtsuk: Well, historically, all cities are in some ways walking cities.

Sally Kornbluth: Mm-hmm.

Andres Sevtsuk: We have few left in the world that are still entirely like that, where just automobiles were never introduced, but those are very rare these days. Places like Venice, Italy.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: There's a sort of interaction between land uses and built environments where we have origins, destinations, and attractions between them for daily travel purposes in the city. We all need to get to work or to school or to social meetings and recreational meetings and so forth. How the land use pattern is structured really induces the demand for different kinds of mobility. If things are far apart and the most logical, rational, and cheapest, comfortable way of getting there by cars, then people will act rationally and drive everywhere. But if a city provides that opportunity of having things close enough and creating pleasant, comfortable, safe experiences, then actually most of us choose to walk.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: It's a pleasant thing to do.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes. Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: It's just incredibly hard in many cities. My research has really looked at, well, what are precisely these configurations that actually trigger that behavior and how can we model that? We've done a huge amount of modeling on traffic at places like MIT over decades and decades and not that much modeling on the non-motorized side of things. I'm very excited about the opportunity to actually take the kind of technical rigor to this domain that's historically been thought of as soft and imprecise.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, that's interesting. I'm wondering with all of these sort of bike systems that are now commercial where people can, like the blue bikes for instance, where people can take a bike and check it out and bring it back and not have to think about ownership or maintenance, et cetera. Do you have any sense of how that's actually affected, first of all, people's utilization and how people rely on cars or anything else? Have you looked at that at all?

Andres Sevtsuk: To some extent, yeah. In places that have invested a lot into safer bike infrastructure, places like Cambridge-

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: ... bicycling has grown tremendously over the last 20 years.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: In fact, when I first moved to Boston in 2004, I remember biking everywhere without a single bike lane and that was normal.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes. Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: Now when I bike in Cambridge, if I don't have a bike lane, I feel-

Sally Kornbluth: Right.

Andres Sevtsuk: ... awkward.

Sally Kornbluth: Right.

Andres Sevtsuk: It's just become-

Sally Kornbluth: I guess it's just the intersections we need to worry about.

Andres Sevtsuk: Right, yeah.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah.

Andres Sevtsuk: You're absolutely right that oftentimes it's a lot easier to design one on a block, but when things get complicated intersections-

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly.

Andres Sevtsuk: ...some people kind of leave it-

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly.

Andres Sevtsuk: But that infrastructure provision makes a huge difference. We see in cities around the world that, in Paris, has had a doubling of bicycling-

Sally Kornbluth: Really?

Andres Sevtsuk: ... within the last year-

Sally Kornbluth: Really?

Andres Sevtsuk: ... roughly. Olympics played a big role in that too.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, of course.

Andres Sevtsuk: But they have very aggressively under Anne Hidalgo's leadership built new infrastructure and it pays off. The behavior follows the-

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah. That's really interesting.

Andres Sevtsuk: We call it induced demand-

Sally Kornbluth: I see.

Andres Sevtsuk: ... induced by infrastructure.

Sally Kornbluth: So what are sort of your favorite walkable and bikeable cities? Are there cities that are doing a particularly good job of this? You mentioned Paris having evolved their usage. What other cities are sort of at the forefront of this?

Andres Sevtsuk: I think cities around the world are generally understanding that transportation and land use dynamics are such a big part of sustainability and climate change mitigation, that we need to do something about it. Cities that are kind of ahead of the game, I think oftentimes are in Europe and East Asia that have been prioritizing dense transit-oriented development for a long time. In Holland, it's almost like every city, not just one particular place. But many cities have, for instance, Paris has made a big dent in biking, not so much walking because it's already been extremely walkable because it's one of the densest cities in Europe. Lisbon has made big strides now, Milan in Europe. But in the US context, too many cities are taking it very seriously. Boston has a 2030 plan that is aiming to achieve quite a aggressive shift in mo share. If you look at any midsize or even large size city in America, they have a strategy to incentivize that mode shift into the future.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes. No, that's interesting. Of my experience in Holland was that everybody, no matter how old, was riding way faster than I could ride. You could see that.

Andres Sevtsuk: Right.

Sally Kornbluth: That was just so embedded in the culture.

Andres Sevtsuk: It is, yeah. That's very interesting history to that too is wasn't always there. Holland was extremely car-centric-

Sally Kornbluth: Really.

Andres Sevtsuk: ... in the 1960s and seventies and there were so many deaths caused by traffic that people protested, especially mothers with prams and strollers whose kids were being run over. That's the story most places around the world is that that kind of shift in policy-making and social support for sustainability doesn't just come out of nowhere. It comes out of organizing and process.

Sally Kornbluth: I'm curious if, thinking about how those places evolved, one is if there's a model for other cities? But the other is, are there pockets of resistance to this?

Andres Sevtsuk: Sure.

Sally Kornbluth: What does that look like? Is it cities that were already built on an urban sprawl and it's just too hard to kind of back design? Or are there other areas of resistance to these sort of arrangements?

Andres Sevtsuk: I think as in almost all domains of life, it's easiest to keep going the way things have been going.

Sally Kornbluth: Right, right.

Andres Sevtsuk: People don't like change all that much and that definitely holds for mobility too. Even here in Cambridge, the most recent council elections were pretty much premised on the support for sustainable mobility or not.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes. Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: We had a very tense election here. In many cities there have been big public debates about even minor changes. I remember a case out of Manhattan Beach around Los Angeles where there was a huge backlash against the bike lane that was being planned on a road. I think oftentimes change is really hard to digest, especially if it goes very fast. Cities need to plan how quickly they introduce some of these large shifts. But yeah, there's certainly a lot of backlash too and largely because people are unfamiliar with the alternative.

Sally Kornbluth: Right.

Andres Sevtsuk: In fact, here in Cambridge too, a lot of businesses are concerned about-

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, interesting.

Andres Sevtsuk: ... sustainable mobility. They think that they lose customers if you take away parking in front of them.

Sally Kornbluth: Right.

Andres Sevtsuk: In fact, most of the research has shown that that would benefit-

Sally Kornbluth: Foot traffic, exactly, is beneficial.

Andres Sevtsuk: People are much more likely to pop into a store if they bike or walk past it, rather than if they drive past it. But I think people generally just haven't seen the alternative so it's safer to hold on to what you know.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes. Yes. Maybe you can give the listeners and give me an idea of what research looks like in this area. What sort of questions do you actually ask? How do you approach them? What's sort of the methodology to get to the answers?

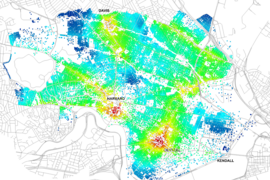

Andres Sevtsuk: A lot of my research looks at cities as networks. We use network science to analyze these land use and mobility dynamics.

Sally Kornbluth: Mm-hmm.

Andres Sevtsuk: How land use patterns create demand for mobility. For instance, recently I've been working on a model of pedestrian activity for the City of New York. The research has involved first creating a citywide precise network of pedestrian infrastructure so that we would have a topologically-interconnected infrastructure network of all sidewalks, crosswalks, and footpaths-

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, I see, uh-huh.

Andres Sevtsuk: ... that represents how you can get around. Then all the origin destination data on top of that, where are our jobs, where are our homes, where are schools, parks, subway stops, and all sorts of destinations that people might want to go to. Then we use network algorithms to estimate how trips flow over the networks from certain origins to certain destinations in a way that actually represents pedestrian behavior.

Sally Kornbluth: I see.

Andres Sevtsuk: We know from behavioral studies how far people are willing to walk, what routes they prefer, how that may vary between men and women or old or young. Then try to bring these findings from the research into the model and accurately simulate how they actually move through the networks. Then we calibrate these models on observed traffic counts to try to get them to precisely reflect what actually is the scene on the streets.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, that's interesting. So then using that information for design, then ...

Andres Sevtsuk: Yes.

Sally Kornbluth: ... you will predict new paths that would be more efficient or encourage more pedestrian traffic?

Andres Sevtsuk: There's lots of interesting applications. The beauty of models is precisely that they not only describe what it is but they can forecast.

Sally Kornbluth: Right, right.

Andres Sevtsuk: If/then kinds of changes. We can, for instance, say, "If the model is built in such a way that it accounts for street characteristics," and we know actually from pedestrian behavior research, what sorts of routes people prefer to walk if presented with alternatives. For instance, how would you walk from here to Harvard? Most likely Mass Ave, but this is a pretty obvious walk. But oftentimes you have hundreds of alternatives you could choose. We know statistically what kinds of routes people prefer. They prefer wider sidewalks, they prefer business frontages on the sidewalks.

Sally Kornbluth: I see, I see, yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: They prefer greenery. They prefer to see other people. If all these features are in the model, then we can also model how changing these features will shift foot traffic in the city. If the City of New York wants to revitalize a neighborhood and bring more foot traffic on a commercial street, they contemplate changes like widening sidewalks or taking away certain traffic features and quieting traffic down. These sorts of models can help forecast what will happen and what will work and what won't work. In fact, all foot traffic and pedestrian-related investments in infrastructure by law require some form of cost benefit analysis.

Sally Kornbluth: Right. Right.

Andres Sevtsuk: These sorts of models are great for that.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: They can help forecast the benefit -

Sally Kornbluth: Interesting.

Andres Sevtsuk: ... and also quantify the cost.

Sally Kornbluth: There's also some natural experiments like during the pandemic when outdoor dining-

Andres Sevtsuk: Yes.

Sally Kornbluth: ... was put in place and people reacted towards the impact of both foot traffic and merchant utilization and accessibility.

Andres Sevtsuk: Yes, indeed.

Sally Kornbluth: That's interesting.

Andres Sevtsuk: Yeah, that was one of those things that a lot of people said, "We'd like that to stay beyond COVID." It's quite nice to see that Cambridge and Boston actually can function with outdoor dining. I think it's kind of adjusted to a certain steady state now where some have disappeared, but a lot of them have actually stayed and it's made our streets I think more vibrant and fun.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, no, absolutely. So I'm just wondering about the overall impact on carbon emissions then. For some of the major cities, you mentioned the difference between Houston and New York, for instance. What do you think the potential upside of this is? In other words, how big an impact could this have if we really could see a shift in major cities to pedestrian bicycle traffic, et cetera?

Andres Sevtsuk: I'm glad you asked that. I think it's a really critical question and I would love to see city design as one of the key features in the climate initiative at the institute because it plays such a huge role that we don't usually look at. Couple of thoughts on that. One is that the sort of sustainable mobility benefits, which I mentioned between Boston and Houston are fourfold or sometimes even larger. They don't only pertain to mobility, in fact. The same kind of denser and more mixed-use city like Boston also saves energy from buildings themselves, not just mobility.

Sally Kornbluth: Sure, sure.

Andres Sevtsuk: That is also very significant, about a 2 1/2 times. An average inhabitant in Houston will spend about five megawatts of residential energy per year. The same type of person in Boston will spend about two because that's not only heating but also cooling.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes, that makes sense.

Andres Sevtsuk: The fact that in car-oriented cities, buildings are low rise, they generally all apart from each other with four walls and a roof that exposes to climate, whether it's heat or cold. It requires mitigation. In cities where we build vertically and more compactly, we have less kind of perimeter to volume ratio in buildings, so we actually have less heat exchange outside. That actually plays a pretty critical role in cutting down building energy demand as well and building emissions. Combined through transportation and heating, cooling, the benefits are really very significant. Oftentimes the question is, well, that's great for building new cities, but what do we do-

Sally Kornbluth: How do you back, yeah.

Andres Sevtsuk: We already have our cities, we have Boston. What are we gonna do about it? Well, the interesting thing is that roughly 30% of all buildings in greater Boston that we see today date from the last 40 years.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, wow.

Andres Sevtsuk: That is just to say, even in cities that don't massively grow, like in the global South, we keep renovating and and rebuilding.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes. Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: MIT is a prime example. We build a lot.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes, yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: That process of continuous building and where we build and how we build, I think will have very significant impacts on climate change. Even in built out cities like Boston, if we can funnel our growth closer to public transit, closer to amenities-

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, that's interesting.

Andres Sevtsuk: ... where we can walk to places, this will take time. But in three, four decades we will see the benefits of all of this. The benefits are not gonna be marginal. They're gonna be big, several times savings compared to developing in suburbs and so forth.

Sally Kornbluth: Interesting.

Andres Sevtsuk: I think that's potentially a really big area of benefit that we should really investigate more with the climate initiative.

Sally Kornbluth: That's interesting. Mentioning the climate initiative, which we call the Climate Project at MIT, we selected intentionally six missions-

Andres Sevtsuk: Yes.

Sally Kornbluth: ... that we really thought could move the needle in significant ways and one of them really is about building healthy, resilient cities. And that brings up sort of an interesting question in my mind, which is the intersection between policy and technology that we see here. So for example, we have a group that's interested in the technology side on cement production that's low carbon or carbon free. I think there was already a building pour in Massachusetts. And so how can policy sort of direct some of these actions? You have to use these sort of materials or you have to have a certain, you know, percentage of the city dedicated to pedestrian traffic, et cetera?

Andres Sevtsuk: Yeah. No, policy is absolutely key when it comes to urban planning and urban development. There are countless examples of the key influences that that has. For instance, we talked earlier about parking and how managing parking can be so effective in mode shift. All the parking we have in buildings today as they're required is an idea that was introduced in the 1950s. Until 1950s, you did not have to build parking with a building.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: People would just dump their cars on the streets and somehow get by. Then people said, "Well that's public resources, you can't do that."

Sally Kornbluth: Right.

Andres Sevtsuk: In five decades or so, we've built cities such that this enormous reservoirs are parking everywhere in private lots and buildings. They're all interconnected into a seamless system that makes driving very easy. Now, I always use this as an example to say that, what if we did that for pedestrians? What if every project that gets built has to do a little bit for a better public realm for pedestrians?

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: A little pocket park here or plaza there, or a public space here. If we stitch them together seamlessly and and let that process run for 50 years, what sort of a city would we get? That's a public policy. Parking is a public policy, right?

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: Then I think similarly, we're seeing today how some of these policies are being introduced, but they're also hard. Massachusetts has a state law now called the MBTA Communities Act, which requires that every community that's next to rail lines, commuter rail and MBTA rail lines, has to up zone and allow more housing into their areas.

Sally Kornbluth: So interesting.

Andres Sevtsuk: Especially affordable housing.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: If you read the news, it's communities are fighting back and saying that, "The state has no business telling us what to do." But of course it's kind of low rise suburban zoning is one of those legacies in Boston that happened after the school busing was required. This was largely racial undertones. People fled inner cities to the suburbs and then zoned them in such a way that you can't have apartments or multifamily homes. Now we're kind of dealing with the legacy of that. I think this is on the right track. I think that states should be zoning up around transit so we can finally get cities built around transit but it has its own backlashes, like we talked about also with sustainable mobility.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, that's really interesting. It does look like some cities are starting to repurpose parking, for example.

Andres Sevtsuk: Yes.

Sally Kornbluth: Taking away parking lots, taking down parking garages-

Andres Sevtsuk: Yes. Right.

Sally Kornbluth: ... and using them for the kind of more dense housing.

Andres Sevtsuk: Absolutely, yeah.

Sally Kornbluth: That you're talking about.

Andres Sevtsuk: There's one in downtown Boston right next to Government Center that was for years and eyesore and now is being redeveloped. I live in Somerville. The City of Somerville is actively actually repurposing parking lots and down zoning parking, which I think is a-

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah. Very interesting.

Andres Sevtsuk: ... music to ears.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, very interesting. I mentioned the pandemic earlier when we were talking about street dining, et cetera, but the pandemic actually led to people leaving the cities, going to the suburbs. I'm wondering, is that trend continuing? Are people moving back to cities? We see, for instance, not only on individual residential issues, but also commercial buildings, trying to fill up again. We hear a lot here about people working from home, which obviously has pluses in terms of the dense, congested cities, but has other side effects on the workplace.

Andres Sevtsuk: Yeah, definitely we saw a very quick shift during COVID towards suburbs, towards places where there was more space. Then as part of that process, we saw a great deal of individual car purchases in the United States. Not only did people shift their residences, a lot more people bought cars.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, interesting.

Andres Sevtsuk: That's the part that makes it really hard to reverberate back quickly because it's a sunk cost. People have bought a new car and they're not not going to use it whereas we do actually see demand for inner city location.

In fact, a lot of people would live in, in Boston or in Cambridge, they just can't afford to because the real estate market doesn't provide enough affordable options. It's too expensive. Even if we see people who want to come back, oftentimes that kind of lifestyle they're now quasi-locked into. Vehicles prevents that as well. There has been a backswing, though. There is many, not even suburbs, but small towns that packed up with people in COVID who said they had the best year ever in 2020 because all of a sudden everybody was flocking there. Now prices have dropped 50% or more because the same people have left back to the cities.

Sally Kornbluth: Got it.

Andres Sevtsuk: But we still don't quite have the supply of housing, especially for a large housing that accommodates families with kids in central city locations. That's the key reason why people stay in suburbs of times because they get the space for cheaper.

Sally Kornbluth: Right. It was funny, I think I saw a talk, and I hope I get this right, by one of your colleagues, Jinhua Zhao, who was analyzing energy utilization. I think we all thought that the more working from home was in essence more energy efficient because there was less commuting, et cetera. But it turned out the patterns by which people heated their home versus heated the buildings meant that cities didn't necessarily realize those gains.

Andres Sevtsuk: Ah, that's super interesting. Yeah, it makes sense to me that if you're two people in a 2,000, even 4,000 square foot house-

Sally Kornbluth: And ran your heat all day.

Andres Sevtsuk: ... versus a small office.

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly. Exactly.

Andres Sevtsuk: That is a shared cost, yeah.

Sally Kornbluth: So I thought that was kind of interesting.

Andres Sevtsuk: Yeah.

Sally Kornbluth: I'm just wondering how you became interested in urban planning. Most 10 year olds don't say, "I want to grow up to be an urban planner." I'm wondering what got you interested in this area?

Andres Sevtsuk: I grew up in Estonia in Northeastern Europe, and I grew up in public housing and I think very much relied on the city as a resource. It was a kind of an experience where everything was in the public sphere rather than the public sphere, the playground, the transportation, the cultural amenities. I think I got my appreciation for cities somewhat from that experience. I studied architecture as an undergraduate, and I lived in Paris during that time, in France. I think as an undergraduate architecture student, I developed this kind of interest in understanding cities during that time in Paris for a few different reasons. On the one hand, Paris has this amazing urban culture where everyone has an opinion about the city.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah.

Andres Sevtsuk: I went to dinners where people still debate whether they should have allowed the pyramid at the Louvre 30 years after.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes, yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: Or the Pompidou from 45 years after.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: The urban culture was sort of, I think, contagious of everybody's interest in questions of city design. As an architect, the complexity fascinates me. In architecture, oftentimes you have a client and so long as you satisfy their demands, you can design a building. If your client is happy with it, that's usually the end of it, so long as it's in budget. But cities are never shaped by individuals. They're an emergent phenomenon that's a result of complex forces, some of which are economics, some of which are cultural, historic, social, real estates. All of them together shape cities. I'm always fascinated by this because we can study cities like people study nature. They're phenomenon where you try to apply scientific methods to make sense of them. Moreover, we don't just need to make sense of them, we also need to make sense of how could we change things. so they're also forward-looking. We need to understand how policy shifts or spatial shifts or other kinds of strategies can shift things in the right direction down the line.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah. It's interesting, as you were talking I was thinking about, we tend to think about the differences between cities. But as you think about your comment about complexity, emergent properties, et cetera, given human behavior, I would assume that there's sort of similar underlying properties that are affecting each city.

Andres Sevtsuk: There are.

Sally Kornbluth: And then they're all sort of variations on the theme.

Andres Sevtsuk: There are, yeah. That's really interesting. I wrote a book called Street Commerce: Creating Vibrant Urban Sidewalks. It's really a book about small-scale business patterns in cities, the kind of street-facing amenities and retail and restaurant-types of businesses. One of the kind of fundamental questions in the book is that if you actually look at it scientifically, there's huge amounts of commonality. The location patterns of small business in cities are in fact highly predictable but yet when you go to a town, every town is very proud of its unique characteristics. You go to Keene, New Hampshire, or Burlington, Vermont or Boston, everybody's very proud of their main street.

Sally Kornbluth: Right.

Andres Sevtsuk: I think it's precisely that patterns that are common versus the traits that are unique that makes cities really interesting. All cities try to kind of deviate from the norm, be special in some ways but we can understand some of the common forces that shape them in a very predictable manner as well.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes. Interesting. Before we sign off, how do you feel about our own local transit system, the T? Do think it's getting better? Any advice for sort of easing Boston traffic?

Andres Sevtsuk: I'm very pleased to see the new MBTA general manager, Philip Eng. I think things have totally turned around since his arrival.

Sally Kornbluth: That's great.

Andres Sevtsuk: I know there's a lot of backlog, a lot of work still needs to be done, but I think things are moving in the right direction at last. I live very close to the new Greenland extensions. I benefit from that a lot. It's really nice to see that we are, again, talking about not just maintaining the old legacy infrastructure, but creating new things like the North-South Station corridor potentially, new subway extensions that are being discussed again. I think this is a truly unique feature that Boston has. Historically, the most expensive or difficult thing is to get the right of ways.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: We already have those.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Andres Sevtsuk: We have these drain corridors that emanate out of the city centers. We just need to operate the service and find the money to support that. I very much like to see that things are shifting in that direction. There's work to be done, but I'm positive about where things are moving towards.

Sally Kornbluth: It's funny because I moved here from Durham, North Carolina, which really has bad public transportation. Even with the inefficiencies I've heard about in the T, I'm so thrilled to be able to hop on the T and go someplace. Of course, Durham has very good, cheap parking. But the sort of benefits I'm hearing as you're saying it, getting better and better, I think it's great.

Andres Sevtsuk: Yeah, it is, yeah.

Sally Kornbluth: I look forward to riding.

Andres Sevtsuk: Then people sometimes complain that it cost the taxpayer a lot of money, it needs to be subsidized, but we need not forget that the driving infrastructure is fully subsidized and has been for decades. It's no different. We need to subsidize what makes us better as a society.

Sally Kornbluth: Right, people need only to think back to the big dig. Boston was ...

Andres Sevtsuk: Yeah.

Sally Kornbluth: ... years being dug up on taxpayer money.

Andres Sevtsuk: Not just that. The largest state expenditures tend to be infrastructure. The roads, every single year, the budget goes largely to maintaining our infrastructure.

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly. Exactly. Well, this was really fun. I learned a lot in this conversation.

Andres Sevtsuk: Thank you for the initiative. It's such a wonderful experience

Sally Kornbluth: To our audience, I hope you've all enjoyed listening to Curiosity Unbounded. I very much hope you'll join us again. I'm Sally Kornbluth, stay curious.

Curiosity Unbounded is a production of MIT News and the Institute Office of Communications in partnership with the Office of the President. This episode was researched, written, and produced by Christine Daniloff, Alexandra Steed, and Melanie Gonick. Our sound engineer is Dave Lishansky. For show notes, transcripts and other episodes, please visit news.mit.edu/podcasts/curiosity-unbounded. Please find us on YouTube, Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts. To learn about the latest developments and updates from MIT, please visit news.mit.edu. You can follow us on Facebook and Instagram at CuriosityUnboundedPodcast.

Thank you for joining us today. We hope you'll tune in next time when Sally will be speaking with Christopher Palmer, an associate professor of finance at MIT. Christopher's research looks at retirement planning and how people save, how renting or owning real estate factors into one's overall quality of life, and the best way for consumers to shop for loans. We hope you'll be there. And remember, stay curious.