More than 100 million people in the United States suffer from metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), characterized by a buildup of fat in the liver. This condition can lead to the development of more severe liver disease that causes inflammation and fibrosis.

In hopes of discovering new treatments for these liver diseases, MIT engineers have designed a new type of tissue model that more accurately mimics the architecture of the liver, including blood vessels and immune cells.

Reporting their findings today in Nature Communications, the researchers showed that this model could accurately replicate the inflammation and metabolic dysfunction that occur in the early stages of liver disease. Such a device could help researchers identify and test new drugs to treat those conditions.

This is the latest study in a larger effort by this team to use these types of tissue models, also known as microphysiological systems, to explore human liver biology, which cannot be easily replicated in mice or other animals.

In another recent paper, the researchers used an earlier version of their liver tissue model to explore how the liver responds to resmetirom. This drug is used to treat an advanced form of liver disease called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), but it is only effective in about 30 percent of patients. The team found that the drug can induce an inflammatory response in liver tissue, which may help to explain why it doesn’t help all patients.

“There are already tissue models that can make good preclinical predictions of liver toxicity for certain drugs, but we really need to better model disease states, because now we want to identify drug targets, we want to validate targets. We want to look at whether a particular drug may be more useful early or later in the disease,” says Linda Griffith, the School of Engineering Professor of Teaching Innovation at MIT, a professor of biological engineering and mechanical engineering, and the senior author of both studies.

Former MIT postdoc Dominick Hellen is the lead author of the resmetirom paper, which appeared Jan. 14 in Communications Biology. Erin Tevonian PhD ’25 and PhD candidate Ellen Kan, both in the Department of Biological Engineering, are the lead authors of today’s Nature Communications paper on the new microphysiological system.

Modeling drug response

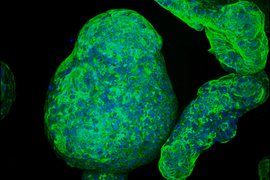

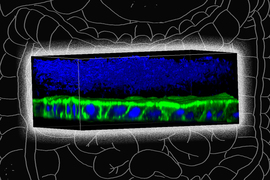

In the Communications Biology paper, Griffith’s lab worked with a microfluidic device that she originally developed in the 1990s, known as the LiverChip. This chip offers a simple scaffold for growing 3D models of liver tissue from hepatocytes, the primary cell type in the liver.

This chip is widely used by pharmaceutical companies to test whether their new drugs have adverse effects on the liver, which is an important step in drug development because most drugs are metabolized by the liver.

For the new study, Griffith and her students modified the chip so that it could be used to study MASLD.

Patients with MASLD, a buildup of fat in the liver, can eventually develop MASH, a more severe disease that occurs when scar tissue called fibrosis forms in the liver. Currently, resmetirom and the GLP-1 drug semaglutide are the only medications that are FDA-approved to treat MASH. Finding new drugs is a priority, Griffith says.

“You’re never declaring victory with liver disease with one drug or one class of drugs, because over the long term there may be patients who can’t use them, or they may not be effective for all patients,” she says.

To create a model of MASLD, the researchers exposed the tissue to high levels of insulin, along with large quantities of glucose and fatty acids. This led to a buildup of fatty tissue and the development of insulin resistance, a trait that is often seen in MASLD patients and can lead to type 2 diabetes.

Once that model was established, the researchers treated the tissue with resmetirom, a drug that works by mimicking the effects of thyroid hormone, which stimulates the breakdown of fat.

To their surprise, the researchers found that this treatment could also lead to an increase in immune signaling and markers of inflammation.

“Because resmetirom is primarily intended to reduce hepatic fibrosis in MASH, we found the result quite paradoxical,” Hellen says. “We suspect this finding may help clinicians and scientists alike understand why only a subset of patients respond positively to the thyromimetic drug. However, additional experiments are needed to further elucidate the underlying mechanism.”

A more realistic liver model

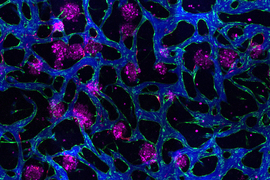

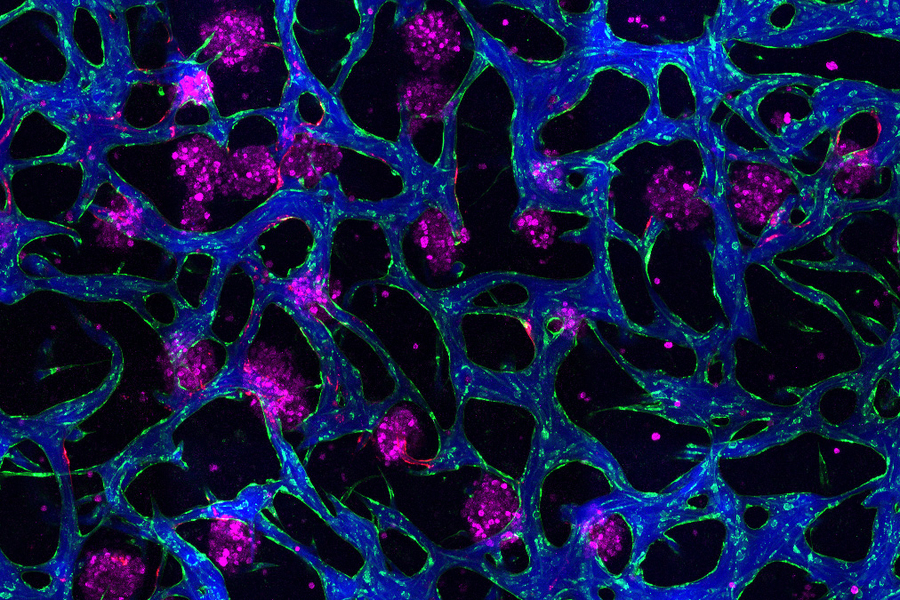

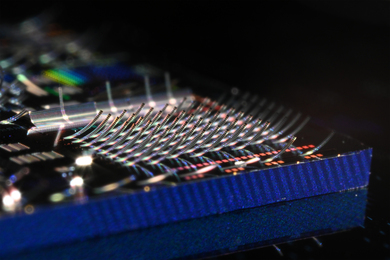

Image: Erin Tevonian and Ellen Kan

In the Nature Communications paper, the researchers reported a new type of chip that allows them to more accurately reproduce the architecture of the human liver. The key advance was developing a way to induce blood vessels to grow into the tissue. These vessels can deliver nutrients and also allow immune cells to flow through the tissue.

“Making more sophisticated models of liver that incorporate features of vascularity and immune cell trafficking that can be maintained over a long time in culture is very valuable,” Griffith says. “The real advance here was showing that we could get an intimate microvascular network through liver tissue and that we could circulate immune cells. This helped us to establish differences between how immune cells interact with the liver cells in a type two diabetes state and a healthy state.”

As the liver tissue matured, the researchers induced insulin resistance by exposing the tissue to increased levels of insulin, glucose, and fatty acids.

As this disease state developed, the researchers observed changes in how hepatocytes clear insulin and metabolize glucose, as well as narrower, leakier blood vessels that reflect microvascular complications often seen in diabetic patients. They also found that insulin resistance leads to an increase in markers of inflammation that attract monocytes into the tissue. Monocytes are the precursors of macrophages, immune cells that help with tissue repair during inflammation and are also observed in the liver of patients with early-stage liver disease.

“This really shows that we can model the immune features of a disease like MASLD, in a way that is all based on human cells,” Griffith says.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship program, NovoNordisk, the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center, and the Siebel Scholars Foundation.