It’s difficult to build devices that replicate the fluid, precise motion of humans, but that might change if we could pull a few (literal) strings.

At least, that’s the idea behind “cable-driven” mechanisms in which running a string through an object generates streamlined movement across an object’s different parts. Take a robotic finger, for example: You could embed a cable through the palm to the fingertip of this object and then pull it to create a curling motion.

While cable-driven mechanisms can create real-time motion to make an object bend, twist, or fold, they can be complicated and time-consuming to assemble by hand. To automate the process, researchers from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have developed an all-in-one 3D printing approach called “Xstrings.” Part design tool, part fabrication method, Xstrings can embed all the pieces together and produce a cable-driven device, saving time when assembling bionic robots, creating art installations, or working on dynamic fashion designs.

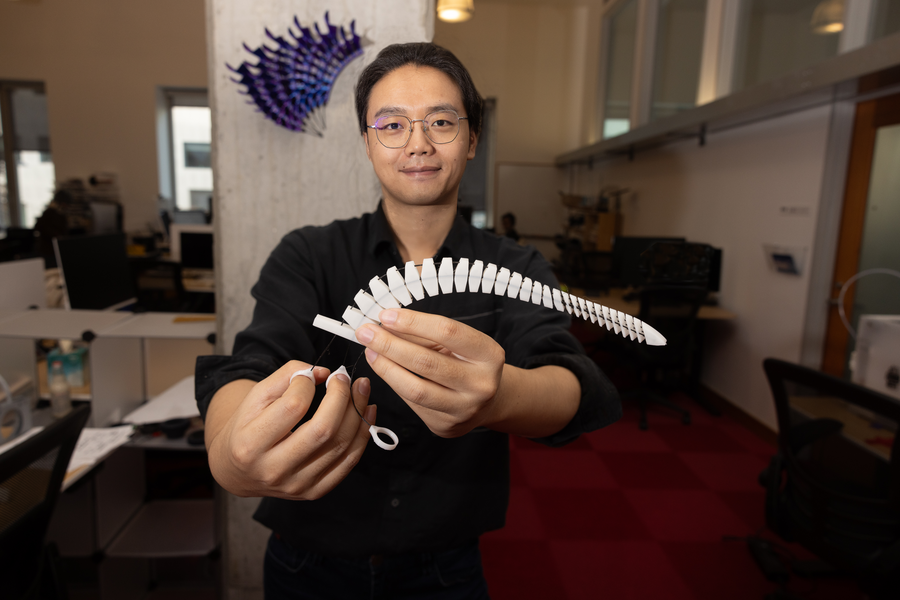

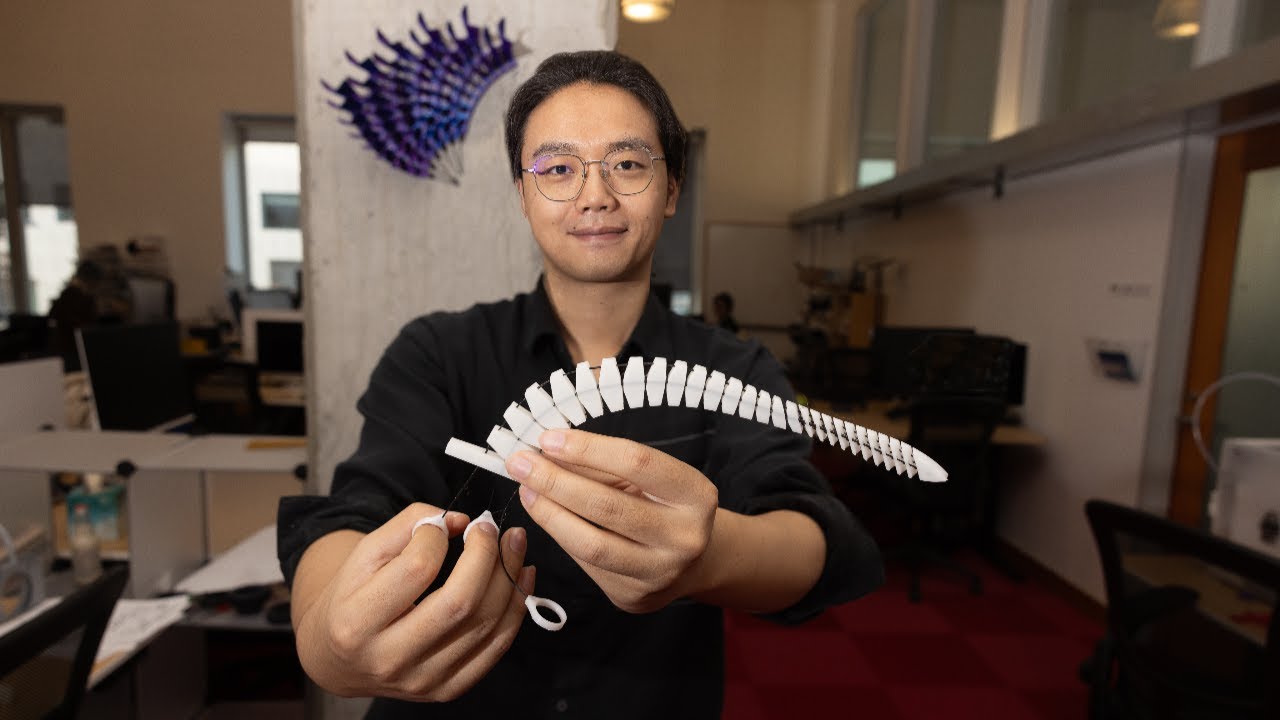

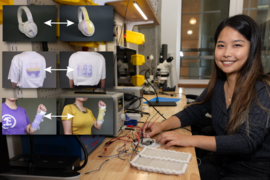

In a paper to be presented at the 2025 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI2025), the researchers used Xstrings to print a range of colorful and unique objects that included a red walking lizard robot, a purple wall sculpture that can open and close like a peacock’s tail, a white tentacle that curls around items, and a white claw that can ball up into a fist to grab objects.

To fabricate these eye-catching mechanisms, Xstrings allows users to fully customize their designs in a software program, sending them to a multi-material 3D printer to bring that creation to life. You can automatically print all the device’s parts in their desired locations in one step, including the cables running through it and the joints that enable its intended motion.

MIT CSAIL postdoc and lead author Jiaji Li says that Xstrings can save engineers time and energy, reducing 40 percent of total production time compared to doing things manually. “Our innovative method can help anyone design and fabricate cable-driven products with a desktop bi-material 3D printer,” says Li.

A new twist on cable-driven fabrication

To use the Xstrings program, users first input a design with specific dimensions, like a rectangular cube divided into smaller pieces with a hole in the middle of each one. You can then choose which way its parts move by selecting different “primitives:” bending, coiling (like a spring), twisting (like a screw), or compressing — and the angle of these motions.

For even more elaborate creations, users can incorporate multiple primitives to create intriguing combinations of motions. If you wanted to make a toy snake, you could include several twists to create a “series” combo, in which a single cord drives a sequence of motions. To create the robot claw, the team embedded multiple cables into a “parallel” combination, where several strings are embedded, to enable each finger to close up into a fist.

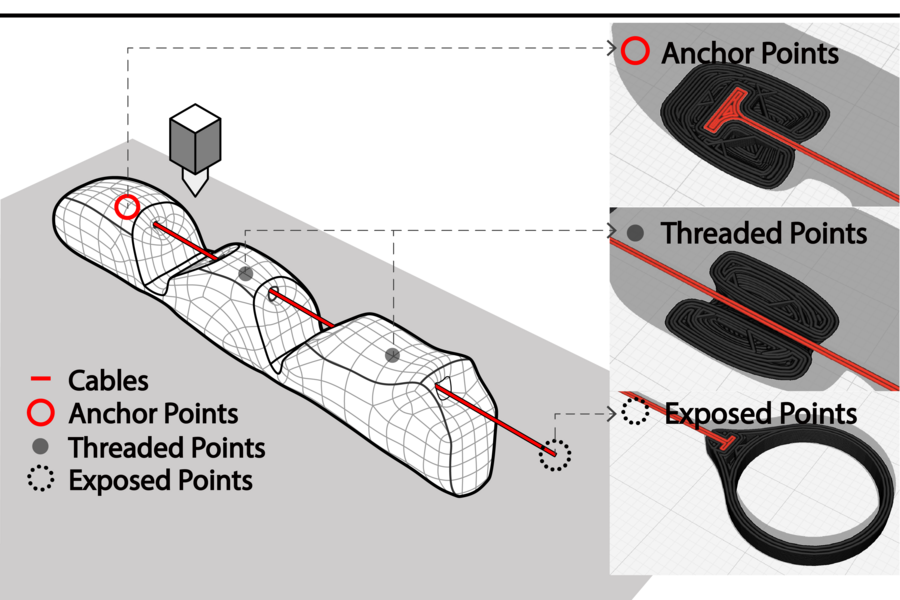

Beyond fine-tuning the way cable-driven mechanisms move, Xstrings also facilitates how cables are integrated into the object. Users can choose exactly how the strings are secured, in terms of where the “anchor” (endpoint), “threaded areas” (or holes within the structure that the cord passes through), and “exposed point” (where you’d pull to operate the device) are located. With a robot finger, for instance, you could choose the anchor to be located at the fingertip, with a cable running through the finger and a pull tag exposed at the other end.

Xstrings also supports diverse joint designs by automatically placing components that are elastic, compliant, or mechanical. This allows the cable to turn as needed as it completes the device’s intended motion.

Driving unique designs across robotics, art, and beyond

Once users have simulated their digital blueprint for a cable-driven item, they can bring it to life via fabrication. Xstrings can send your design to a fused deposition modeling 3D printer, where plastic is melted down into a nozzle before the filaments are poured out to build structures up layer by layer.

Xstrings uses this technique to lay out cables horizontally and build around them. To ensure their method would successfully print cable-driven mechanisms, the researchers carefully tested their materials and printing conditions.

For example, the researchers found that their strings only broke after being pulled up and down by a mechanical device more than 60,000 times. In another test, the team discovered that printing at 260 degrees Celsius with a speed of 10-20 millimeters per second was ideal for producing their many creative items.

“The Xstrings software can bring a variety of ideas to life,” says Li. “It enables you to produce a bionic robot device like a human hand, mimicking our own gripping capabilities. You can also create interactive art pieces, like a cable-driven sculpture with unique geometries, and clothes with adjustable flaps. One day, this technology could enable the rapid, one-step creation of cable-driven robots in outer space, even within highly confined environments such as space stations or extraterrestrial bases.”

The team’s approach offers plenty of flexibility and a noticeable speed boost to fabricating cable-driven objects. It creates objects that are rigid on the outside, but soft and flexible on the inside; in the future, they may look to develop objects that are soft externally but rigid internally, much like humans’ skin and bones. They’re also considering using more resilient cables, and, instead of just printing strings horizontally, embedding ones that are angled or even vertical.

Li wrote the paper with Zhejiang University master’s student Shuyue Feng; Tsinghua University master’s student Yujia Liu; Zhejiang University assistant professor and former MIT Media Lab visiting researcher Guanyun Wang; and three CSAIL members: Maxine Perroni-Scharf, an MIT PhD student in electrical engineering and computer science; Emily Guan, a visiting researcher; and senior author Stefanie Mueller, the TIBCO Career Development Associate Professor in the MIT departments of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and Mechanical Engineering, and leader of the HCI Engineering Group.

This research was supported, in part, by a postdoctoral research fellowship from Zhejiang University, and the MIT-GIST Program.