Audio

Art restoration takes steady hands and a discerning eye. For centuries, conservators have restored paintings by identifying areas needing repair, then mixing an exact shade to fill in one area at a time. Often, a painting can have thousands of tiny regions requiring individual attention. Restoring a single painting can take anywhere from a few weeks to over a decade.

In recent years, digital restoration tools have opened a route to creating virtual representations of original, restored works. These tools apply techniques of computer vision, image recognition, and color matching, to generate a “digitally restored” version of a painting relatively quickly.

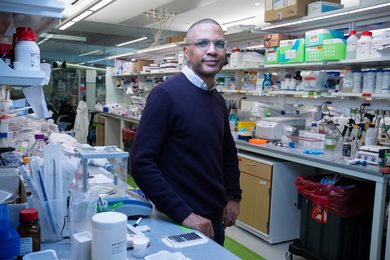

Still, there has been no way to translate digital restorations directly onto an original work, until now. In a paper appearing today in the journal Nature, Alex Kachkine, a mechanical engineering graduate student at MIT, presents a new method he’s developed to physically apply a digital restoration directly onto an original painting.

The restoration is printed on a very thin polymer film, in the form of a mask that can be aligned and adhered to an original painting. It can also be easily removed. Kachkine says that a digital file of the mask can be stored and referred to by future conservators, to see exactly what changes were made to restore the original painting.

“Because there’s a digital record of what mask was used, in 100 years, the next time someone is working with this, they’ll have an extremely clear understanding of what was done to the painting,” Kachkine says. “And that’s never really been possible in conservation before.”

As a demonstration, he applied the method to a highly damaged 15th century oil painting. The method automatically identified 5,612 separate regions in need of repair, and filled in these regions using 57,314 different colors. The entire process, from start to finish, took 3.5 hours, which he estimates is about 66 times faster than traditional restoration methods.

Kachkine acknowledges that, as with any restoration project, there are ethical issues to consider, in terms of whether a restored version is an appropriate representation of an artist’s original style and intent. Any application of his new method, he says, should be done in consultation with conservators with knowledge of a painting’s history and origins.

“There is a lot of damaged art in storage that might never be seen,” Kachkine says. “Hopefully with this new method, there’s a chance we’ll see more art, which I would be delighted by.”

Digital connections

The new restoration process started as a side project. In 2021, as Kachkine made his way to MIT to start his PhD program in mechanical engineering, he drove up the East Coast and made a point to visit as many art galleries as he could along the way.

“I’ve been into art for a very long time now, since I was a kid,” says Kachkine, who restores paintings as a hobby, using traditional hand-painting techniques. As he toured galleries, he came to realize that the art on the walls is only a fraction of the works that galleries hold. Much of the art that galleries acquire is stored away because the works are aged or damaged, and take time to properly restore.

“Restoring a painting is fun, and it’s great to sit down and infill things and have a nice evening,” Kachkine says. “But that’s a very slow process.”

As he has learned, digital tools can significantly speed up the restoration process. Researchers have developed artificial intelligence algorithms that quickly comb through huge amounts of data. The algorithms learn connections within this visual data, which they apply to generate a digitally restored version of a particular painting, in a way that closely resembles the style of an artist or time period. However, such digital restorations are usually displayed virtually or printed as stand-alone works and cannot be directly applied to retouch original art.

“All this made me think: If we could just restore a painting digitally, and effect the results physically, that would resolve a lot of pain points and drawbacks of a conventional manual process,” Kachkine says.

“Align and restore”

For the new study, Kachkine developed a method to physically apply a digital restoration onto an original painting, using a 15th-century painting that he acquired when he first came to MIT. His new method involves first using traditional techniques to clean a painting and remove any past restoration efforts.

“This painting is almost 600 years old and has gone through conservation many times,” he says. “In this case there was a fair amount of overpainting, all of which has to be cleaned off to see what’s actually there to begin with.”

He scanned the cleaned painting, including the many regions where paint had faded or cracked. He then used existing artificial intelligence algorithms to analyze the scan and create a virtual version of what the painting likely looked like in its original state.

Then, Kachkine developed software that creates a map of regions on the original painting that require infilling, along with the exact colors needed to match the digitally restored version. This map is then translated into a physical, two-layer mask that is printed onto thin polymer-based films. The first layer is printed in color, while the second layer is printed in the exact same pattern, but in white.

“In order to fully reproduce color, you need both white and color ink to get the full spectrum,” Kachkine explains. “If those two layers are misaligned, that’s very easy to see. So I also developed a few computational tools, based on what we know of human color perception, to determine how small of a region we can practically align and restore.”

Kachkine used high-fidelity commercial inkjets to print the mask’s two layers, which he carefully aligned and overlaid by hand onto the original painting and adhered with a thin spray of conventional varnish. The printed films are made from materials that can be easily dissolved with conservation-grade solutions, in case conservators need to reveal the original, damaged work. The digital file of the mask can also be saved as a detailed record of what was restored.

For the painting that Kachkine used, the method was able to fill in thousands of losses in just a few hours. “A few years ago, I was restoring this baroque Italian painting with probably the same order magnitude of losses, and it took me nine months of part-time work,” he recalls. “The more losses there are, the better this method is.”

He estimates that the new method can be orders of magnitude faster than traditional, hand-painted approaches. If the method is adopted widely, he emphasizes that conservators should be involved at every step in the process, to ensure that the final work is in keeping with an artist’s style and intent.

“It will take a lot of deliberation about the ethical challenges involved at every stage in this process to see how can this be applied in a way that’s most consistent with conservation principles,” he says. “We’re setting up a framework for developing further methods. As others work on this, we’ll end up with methods that are more precise.”

This work was supported, in part, by the John O. and Katherine A. Lutz Memorial Fund. The research was carried out, in part, through the use of equipment and facilities at MIT.Nano, with additional support from the MIT Microsystems Technology Laboratories, the MIT Department of Mechanical Engineering, and the MIT Libraries.