Audio

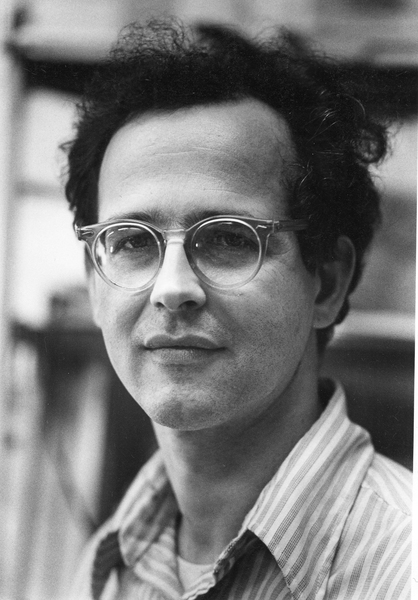

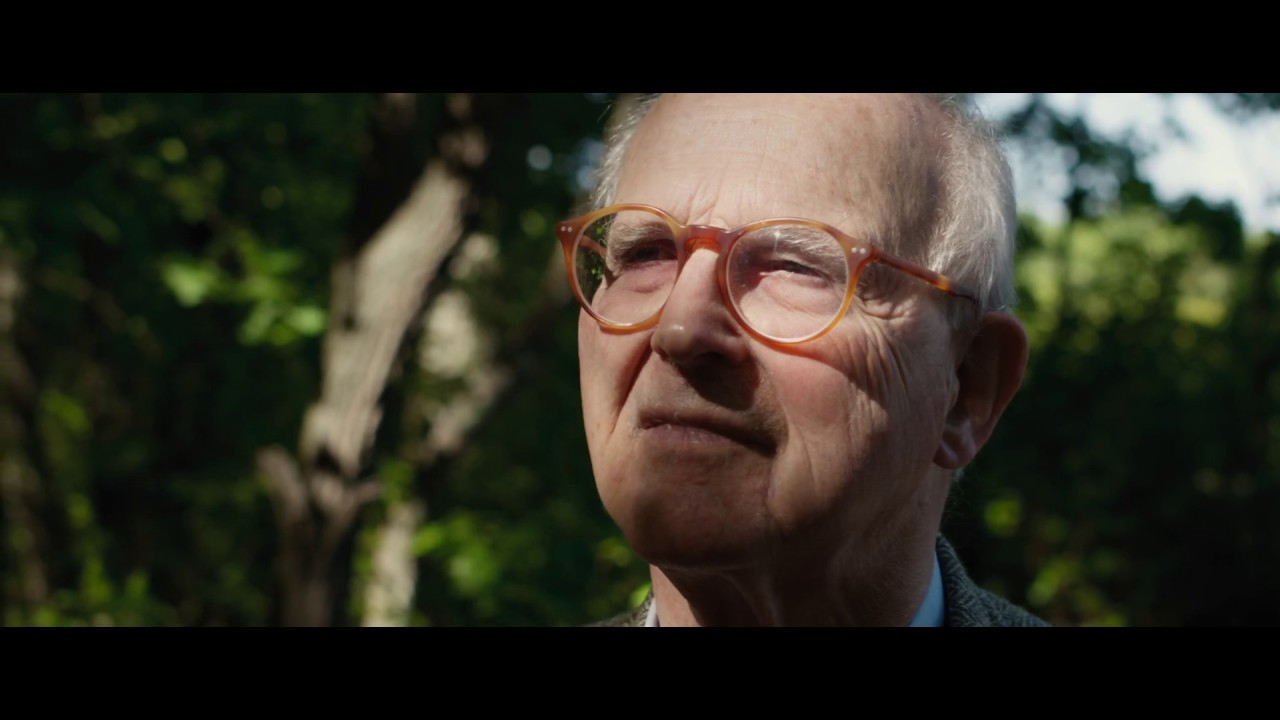

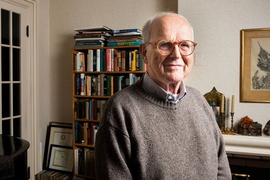

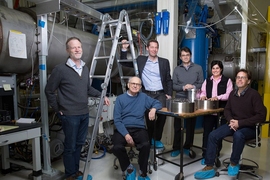

MIT Professor Emeritus Rainer Weiss ’55, PhD ’62, a renowned experimental physicist and Nobel laureate whose groundbreaking work confirmed a longstanding prediction about the nature of the universe, passed away on Aug. 25. He was 92.

Weiss conceived of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) for detecting ripples in space-time known as gravitational waves, and was later a leader of the team that built LIGO and achieved the first-ever detection of gravitational waves. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for this work in 2017. Together with international collaborators, he and his colleagues at LIGO would go on to detect many more of these cosmic reverberations, opening up a new way for scientists to view the universe.

During his remarkable career, Weiss also developed a more precise atomic clock and figured out how to measure the spectrum of the cosmic microwave background via a weather balloon. He later co-founded and advanced the NASA Cosmic Background Explorer project, whose measurements helped support the Big Bang theory describing the expansion of the universe.

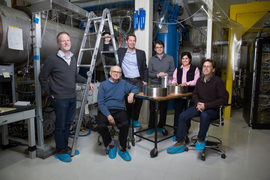

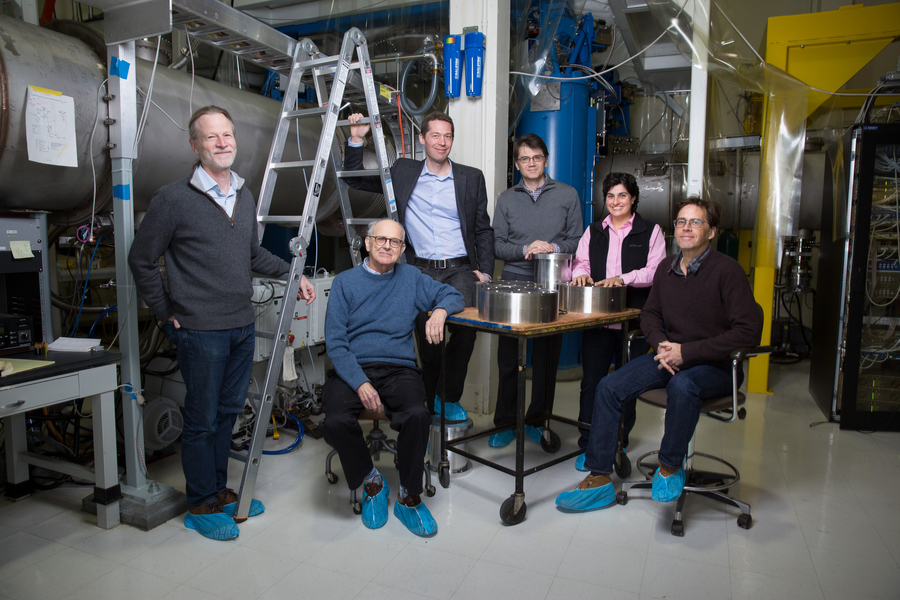

“Rai leaves an indelible mark on science and a gaping hole in our lives,” says Nergis Mavalvala PhD ’97, dean of the MIT School of Science and the Curtis and Kathleen Marble Professor of Astrophysics. As a doctoral student with Weiss in the 1990s, Mavalvala worked with him to build an early prototype of a gravitational-wave detector as part of her PhD thesis. “He will be so missed but has also gifted us a singular legacy. Every gravitational wave event we observe will remind us of him, and we will smile. I am indeed heartbroken, but also so grateful for having him in my life, and for the incredible gifts he has given us — of passion for science and discovery, but most of all to always put people first.” she says.

A member of the MIT physics faculty since 1964, Weiss was known as a committed mentor and teacher, as well as a dedicated researcher.

“Rai’s ingenuity and insight as an experimentalist and a physicist were legendary,” says Deepto Chakrabarty, the William A. M. Burden Professor in Astrophysics and head of the Department of Physics. “His no-nonsense style and gruff manner belied a very close, supportive and collaborative relationship with his students, postdocs, and other mentees. Rai was a thoroughly MIT product.”

“Rai held a singular position in science: He was the creator of two fields — measurements of the cosmic microwave background and of gravitational waves. His students have gone on to lead both fields and carried Rai’s rigor and decency to both. He not only created a huge part of important science, he also populated them with people of the highest caliber and integrity,” says Peter Fisher, the Thomas A. Frank Professor of Physics and former head of the physics department.

Enabling a new era in astrophysics

LIGO is a system of two identical detectors located 1,865 miles apart. By sending finely tuned lasers back and forth through the detectors, scientists can detect perturbations caused by gravitational waves, whose existence was proposed by Albert Einstein. These discoveries illuminate ancient collisions and other events in the early universe, and have confirmed Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Today, the LIGO Scientific Collaboration involves hundreds of scientists at MIT, Caltech, and other universities, and with the Virgo and KAGRA observatories in Italy and Japan makes up the global LVK Collaboration — but five decades ago, the instrument concept was an MIT class exercise conceived by Weiss.

As he told MIT News in 2017, in generating the initial idea, Weiss wondered: “What’s the simplest thing I can think of to show these students that you could detect the influence of a gravitational wave?”

To realize the audacious design, Weiss teamed up in 1976 with physicist Kip Thorne, who, based in part on conversations with Weiss, soon seeded the creation of a gravitational wave experiment group at Caltech. The two formed a collaboration between MIT and Caltech, and in 1979, the late Scottish physicist Ronald Drever, then of the University of Glasgow, joined the effort at Caltech. The three scientists — who became the co-founders of LIGO — worked to refine the dimensions and scientific requirements for an instrument sensitive enough to detect a gravitational wave. Barry Barish later joined the team at Caltech, helping to secure funding and bring the detectors to completion.

After receiving support from the National Science Foundation, LIGO broke ground in the mid-1990s, constructing interferometric detectors in Hanford, Washington, and in Livingston, Louisiana.

Years later, when he shared the Nobel Prize with Thorne and Barish for his work on LIGO, Weiss noted that hundreds of colleagues had helped to push forward the search for gravitational waves.

“The discovery has been the work of a large number of people, many of whom played crucial roles,” Weiss said at an MIT press conference. “I view receiving this [award] as sort of a symbol of the various other people who have worked on this.”

He continued: “This prize and others that are given to scientists is an affirmation by our society of [the importance of] gaining information about the world around us from reasoned understanding of evidence.”

“While I have always been amazed and guided by Rai’s ingenuity, integrity, and humility, I was most impressed by his breadth of vision and ability to move between worlds,” says Matthew Evans, the MathWorks Professor of Physics. “He could seamlessly shift from the smallest technical detail of an instrument to the global vision for a future observatory. In the last few years, as the idea for a next-generation gravitational-wave observatory grew, Rai would often be at my door, sharing ideas for how to move the project forward on all levels. These discussions ranged from quantum mechanics to global politics, and Rai’s insights and efforts have set the stage for the future.”

A lifelong fascination with hard problems

Weiss was born in 1932 in Berlin. The young family fled Nazi Germany to Prague and then emigrated to New York City, where Weiss grew up with a love for classical music and electronics, earning money by fixing radios.

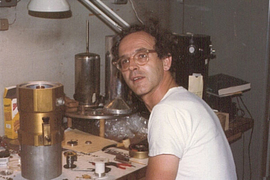

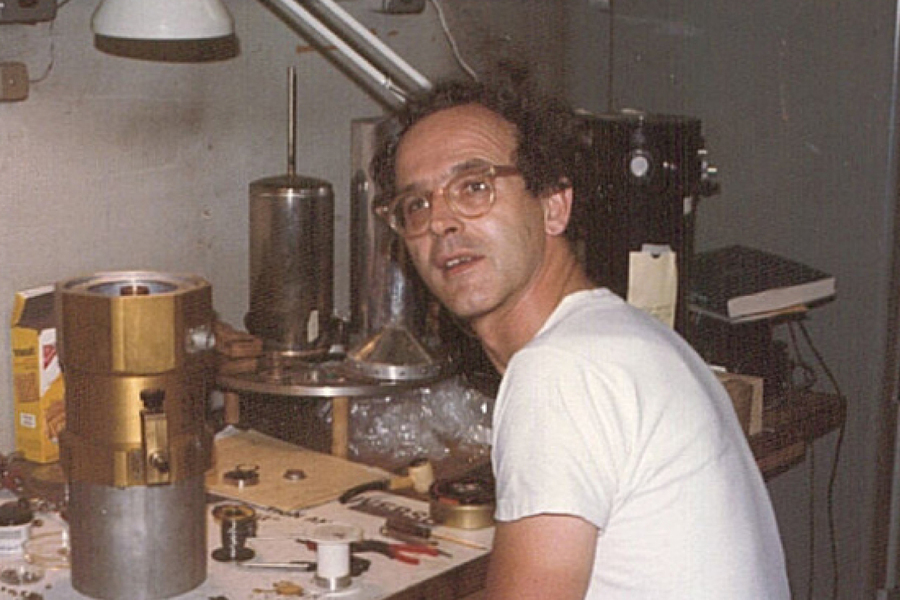

He enrolled at MIT, then dropped out of school in his junior year, only to return shortly after, taking a job as a technician in the former Building 20. There, Weiss met physicist Jerrold Zacharias, who encouraged him in finishing his undergraduate degree in 1955 and his PhD in 1962.

Weiss spent some time at Princeton University as a postdoc in the legendary group led by Robert Dicke, where he developed experiments to test gravity. He returned to MIT as an assistant professor in 1964, starting a new research group in the Research Laboratory of Electronics dedicated to research in cosmology and gravitation.

With the money he received from the Nobel Prize, Weiss established the Barish-Weiss Fellowship to support student research in the MIT Department of Physics.

Weiss received numerous awards and honors in addition to the Nobel Prize, including the Medaille de l’ADION, the 2006 Gruber Prize in Cosmology, and the 2007 Einstein Prize of the American Physical Society. He was a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Physical Society, as well as a member of the National Academy of Sciences. In 2016, Weiss received a Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics, the Gruber Prize in Cosmology, the Shaw Prize in Astronomy, and the Kavli Prize in Astrophysics, all shared with Drever and Thorne. He also shared the Princess of Asturias Award for Technical and Scientific Research with Thorne, Barry Barish of Caltech, and the LIGO Scientific Collaboration.

Weiss is survived by his wife, Rebecca; his daughter, Sarah, and her husband, Tony; his son, Benjamin, and his wife, Carla; and a grandson, Sam, and his wife, Constance. Details about a memorial are forthcoming.

This article may be updated.