Nuclear physicist and MIT Professor Emeritus Lee Grodzins died on March 6 at his home in the Maplewood Senior Living Community at Weston, Massachusetts. He was 98.

Grodzins was a pioneer in nuclear physics research. He was perhaps best known for the highly influential experiment determining the helicity of the neutrino, which led to a key understanding of what's known as the weak interaction. He was also the founder of Niton Corp. and the nonprofit Cornerstones of Science, and was a co-founder of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

He retired in 1999 after serving as an MIT physics faculty member for 40 years. As a member of the Laboratory for Nuclear Science (LNS), he initiated the relativistic heavy-ion physics program. He published over 170 scientific papers and held 64 U.S. patents.

“Lee was a very good experimental physicist, especially with his hands making gadgets,” says Heavy Ion Group and Francis L. Friedman Professor Emeritus Wit Busza PhD ’64. “His enthusiasm for physics spilled into his enthusiasm for how physics was taught in our department.”

Industrious son of immigrants

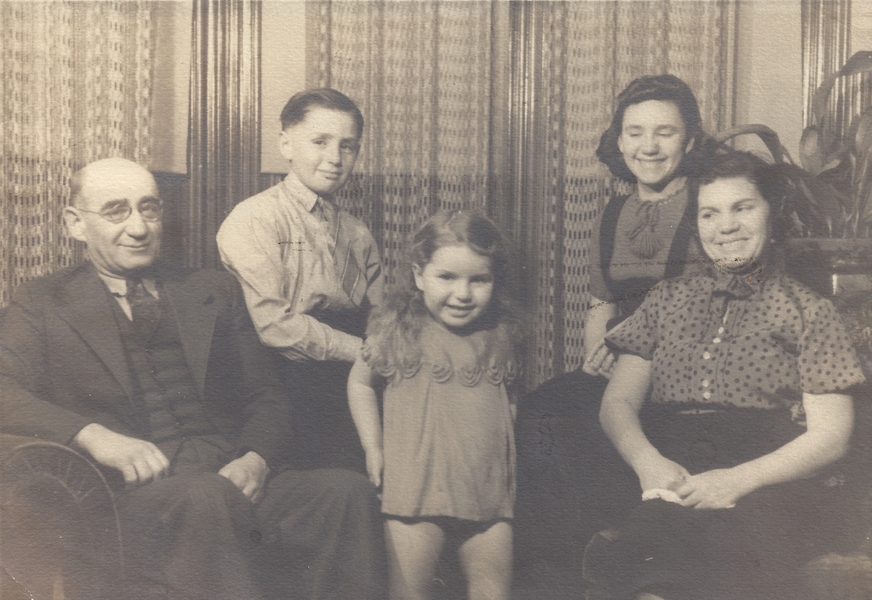

Grodzins was born July 10, 1926, in Lowell, Massachusetts, the middle child of Eastern European Jewish immigrants David and Taube Grodzins. He grew up in Manchester, New Hampshire. His two sisters were Ethel Grodzins Romm, journalist, author, and businesswoman who later ran his company, Niton Corp.; and Anne Lipow, who became a librarian and library science expert.

His father, who ran a gas station and a used-tire business, died when Lee was 15. To help support his family, Lee sold newspapers, a business he grew into the second-largest newspaper distributor in Manchester.

At 17, Grodzins attended the University of New Hampshire, graduating in less than three years with a degree in mechanical engineering. However, he decided to be a physicist after disagreeing with a textbook that used the word “never.”

“I was pretty good in math and was undecided about my future,” Grodzins said in a 1958 New York Daily News article. “It wasn’t until my senior year that I unexpectedly realized I wanted to be a physicist. I was reading a physics text one day when suddenly this sentence hit me: ‘We will never be able to see the atom.’ I said to myself that that was as stupid a statement as I’d ever read. What did he mean ‘never!’ I got so annoyed that I started devouring other writers to see what they had to say and all at once I found myself in the midst of modern physics.”

He wrote his senior thesis on “Atomic Theory.”

After graduating in 1946, he approached potential employers by saying, “I have a degree in mechanical engineering, but I don’t want to be one. I’d like to be a physicist, and I’ll take anything in that line at whatever you will pay me.”

He accepted an offer from General Electric’s Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York, where he worked in fundamental nuclear research building cosmic ray detectors, while also pursuing his master’s degree at Union College. “I had a ball,” he recalled. “I stayed in the lab 12 hours a day. They had to kick me out at night.”

Brookhaven

After earning his PhD from Purdue University in 1954, he spent a year as a lecturer there, before becoming a researcher at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) with Maurice Goldhaber’s nuclear physics group, probing the properties of the nuclei of atoms.

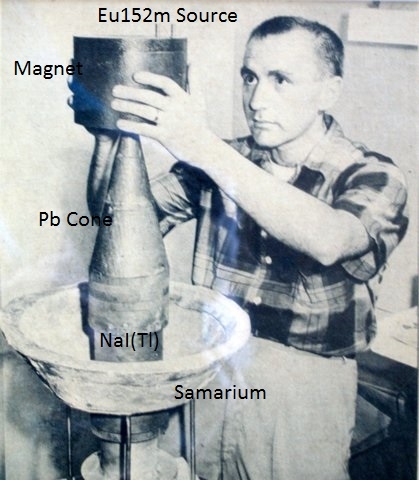

In 1957, he, with Goldhaber and Andy Sunyar, used a simple table-top experiment to measure the helicity of the neutrino. Helicity characterizes the alignment of a particle’s intrinsic spin vector with that particle’s direction of motion.

The research provided new support for the idea that the principle of conservation of parity — which had been accepted for 30 years as a basic law of nature before being disproven the year before, leading to the 1957 Nobel Prize in Physics — was not as inviolable as the scientists thought it was, and did not apply to the behavior of some subatomic particles.

The experiment took about 10 days to complete, followed by a month of checks and rechecks. They submitted a letter on “Helicity of Neutrinos” to Physical Review on Dec. 11, 1957, and a week later, Goldhaber told a Stanford University audience that the neutrino is left-handed, meaning that the weak interaction was probably one force. This work proved crucial to our understanding of the weak interaction, the force that governs nuclear beta decay.

“It was a real upheaval in our understanding of physics,” says Grodzins’ longtime colleague Stephen Steadman. The breakthrough was commemorated in 2008, with a conference at BNL on “Neutrino Helicity at 50.”

Steadman also recalls Grodzins’ story about one night at Brookhaven, where he was working on an experiment that involved a radioactive source inside a chamber. Lee noticed that a vacuum pump wasn’t working, so he tinkered with it a while before heading home. Later that night, he gets a call from the lab. “They said, ‘Don't go anywhere!’” recalls Steadman. It turns out the radiation source in the lab had exploded, and the pump filled the lab with radiation. “They were actually able to trace his radioactive footprints from the lab to his home,” says Steadman. “He kind of shrugged it off.”

The MIT years

Grodzins joined the faculty of MIT in 1959, where he taught physics for four decades. He inherited Robley Evans’ Radiation Laboratory, which used radioactive sources to study properties of nuclei, and led the Relativistic Heavy Ion Group, which was affiliated with the LNS.

In 1972, he launched a program at BNL using the then-new Tandem Van de Graaff accelerator to study interactions of heavy ions with nuclei. “As the BNL tandem was getting commissioned, we started a program, together with Doug Cline at the University of Rochester, tandem to investigate Coulomb-nuclear interference,” says Steadman, a senior research scientist at LNS. “The experimental results were decisive but somewhat controversial at the time. We clearly detected the interference effect.” The experimental work was published in Physical Review Letters.

Grodzins’ team looked for super-heavy elements using the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Super-Hilac, investigated heavy-ion fission and other heavy-ion reactions, and explored heavy-ion transfer reactions. The latter research showed with precise detail the underlying statistical behavior of the transfer of nucleons between the heavy-ion projectile and target, using a theoretical statistical model of Surprisal Analysis developed by Rafi Levine and his graduate student. Recalls Steadman, “these results were both outstanding in their precision and initially controversial in interpretation.”

In 1985, he carried out the first computer axial tomographic experiment using synchrotron radiation, and in 1987, his group was involved in the first run of Experiment 802, a collaborative experiment with about 50 scientists from around the world that studied relativistic heavy ion collisions at Brookhaven. The MIT responsibility was to build the drift chambers and design the bending magnet for the experiment.

“He made significant contributions to the initial design and construction phases, where his broad expertise and knowledge of small area companies with unique capabilities was invaluable,” says George Stephans, physics senior lecturer and senior research scientist at MIT.

Professor emeritus of physics Rainer Weiss ’55, PhD ’62 recalls working on a Mossbauer experiment to establish if photons changed frequency as they traveled through bright regions. “It was an idea held by some to explain the ‘apparent’ red shift with distance in our universe,” says Weiss. “We became great friends in the process, and of course, amateur cosmologists.”

“Lee was great for developing good ideas,” Steadman says. “He would get started on one idea, but then get distracted with another great idea. So, it was essential that the team would carry these experiments to their conclusion: they would get the papers published.”

MIT mentor

Before retiring in 1999, Lee supervised 21 doctoral dissertations and was an early proponent of women graduate students in physics. He also oversaw the undergraduate thesis of Sidney Altman, who decades later won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. For many years, he helped teach the Junior Lab required of all undergraduate physics majors. He got his favorite student evaluation, however, for a different course, billed as offering a “superficial overview” of nuclear physics. The comment read: “This physics course was not superficial enough for me.”

“He really liked to work with students,” says Steadman. “They could always go into his office anytime. He was a very supportive mentor.”

“He was a wonderful mentor, avuncular and supportive of all of us,” agrees Karl van Bibber ’72, PhD ’76, now at the University of California at Berkeley. He recalls handing his first paper to Grodzins for comments. “I was sitting at my desk expecting a pat on the head. Quite to the contrary, he scowled, threw the manuscript on my desk and scolded, ‘Don't even pick up a pencil again until you've read a Hemingway novel!’ … The next version of the paper had an average sentence length of about six words; we submitted it, and it was immediately accepted by Physical Review Letters.”

Van Bibber has since taught the “Grodzins Method” in his graduate seminars on professional orientation for scientists and engineers, including passing around a few anthologies of Hemingway short stories. “I gave a copy of one of the dog-eared anthologies to Lee at his 90th birthday lecture, which elicited tears of laughter.”

Early in George Stephans’ MIT career as a research scientist, he worked with Grodzins’ newly formed Relativistic Heavy Ion Group. “Despite his wide range of interests, he paid close attention to what was going on and was always very supportive of us, especially the students. He was a very encouraging and helpful mentor to me, as well as being always pleasant and engaging to work with. He actively pushed to get me promoted to principal research scientist relatively early, in recognition of my contributions.”

“He always seemed to know a lot about everything, but never acted condescending,” says Stephans. “He seemed happiest when he was deeply engaged digging into the nitty-gritty details of whatever unique and unusual work one of these companies was doing for us.”

Al Lazzarini ’74, PhD ’78 recalls Grodzins’ investigations using proton-induced X-ray emission (PIXE) as a sensitive tool to measure trace elemental amounts. “Lee was a superb physicist,” says Lazzarini. “He gave an enthralling seminar on an investigation he had carried out on a lock of Napoleon’s hair, looking for evidence of arsenic poisoning.”

Robert Ledoux ’78, PhD ’81, a former professor of physics at MIT who is now program director of the U.S. Advanced Research Projects Agency with the Department of Energy, worked with Grodzins as both a student and colleague. “He was a ‘nuclear physicist’s physicist’ — a superb experimentalist who truly loved building and performing experiments in many areas of nuclear physics. His passion for discovery was matched only by his generosity in sharing knowledge.”

The research funding crisis starting in 1969 led Grodzins to become concerned that his graduate students would not find careers in the field. He helped form the Economic Concerns Committee of the American Physical Society, for which he produced a major report on the “Manpower Crisis in Physics” (1971), and presented his results before the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and at the Karlsruhe National Lab in Germany.

Grodzins played a significant role in bringing the first Chinese graduate students to MIT in the 1970s and 1980s.

One of the students he welcomed was Huan Huang PhD ’90. “I am forever grateful to him for changing my trajectory,” says Huang, now at the University of California at Los Angeles. “His unwavering support and ‘go do it’ attitude inspired us to explore physics at the beginning of a new research field of high energy heavy ion collisions in the 1980s. I have been trying to be a ‘nice professor’ like Lee all my academic career.”

Even after he left MIT, Grodzins remained available for his former students. “Many tell me how much my lifestyle has influenced them, which is gratifying,” Huang says. “They’ve been a central part of my life. My biography would be grossly incomplete without them.”

Niton Corp. and post-MIT work

Grodzins liked what he called “tabletop experiments,” like the one used in his 1957 neutrino experiment, which involved a few people building a device that could fit on a tabletop. “He didn’t enjoy working in large collaborations, which nuclear physics embraced.” says Steadman. “I think that’s why he ultimately left MIT.”

In the 1980s, he launched what amounted to a new career in detection technology. In 1987, after developing a scanning proton-induced X-ray microspectrometer for use measuring elemental concentrations in air, he founded the Niton Corp., which developed, manufactured, and marketed test kits and instruments to measure radon gas in buildings, lead-based paint detection, and other nondestructive testing applications. (“Niton” is an obsolete term for radon.)

“At the time, there was a big scare about radon in New England, and he thought he could develop a radon detector that was inexpensive and easy to use,” says Steadman. “His radon detector became a big business.”

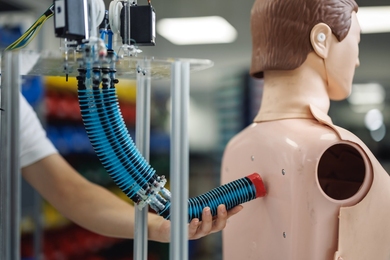

He later developed devices to detect explosives, drugs, and other contraband in luggage and cargo containers. Handheld devices used X-ray fluorescence to determine the composition of metal alloys and to detect other materials. The handheld XL Spectrum Analyzer could detect buried and surface lead on painted surfaces, to protect children living in older homes. Three Niton X-ray fluorescence analyzers earned R&D 100 awards.

“Lee was very technically gifted,” says Steadman.

In 1999, Grodzins retired from MIT and devoted his energies to industry, including directing the R&D group at Niton.

His sister Ethel Grodzins Romm was the president and CEO of Niton, followed by his son Hal. Many of Niton’s employees were MIT graduates. In 2005, he and his family sold Niton to Thermo Fisher Scientific, where Lee remained as a principal scientist until 2010.

In the 1990s, he was vice president of American Science and Engineering, and between the ages of 70 and 90, he was awarded three patents a year.

“Curiosity and creativity don’t stop after a certain age,” Grodzins said to UNH Today. “You decide you know certain things, and you don’t want to change that thinking. But thinking outside the box really means thinking outside your box.”

“I miss his enthusiasm,” says Steadman. “I saw him about a couple of years ago and he was still on the move, always ready to launch a new effort, and he was always trying to pull you into those efforts.”

A better world

In the 1950s, Grodzins and other Brookhaven scientists joined the American delegation at the Second United Nations International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy in Geneva.

Early on, he joined several Manhattan Project alums at MIT in their concern about the consequences of nuclear bombs. In Vietnam-era 1969, Grodzins co-founded the Union of Concerned Scientists, which calls for scientific research to be directed away from military technologies and toward solving pressing environmental and social problems. He served as its chair in 1970 and 1972. He also chaired committees for the American Physical Society and the National Research Council.

As vice president for advanced products at American Science and Engineering, which made homeland security equipment, he became a consultant on airport security, especially following the 9/11 attacks. As an expert witness, he testified at the celebrated trial to determine whether Pan Am was negligent for the bombing of Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, and he took part in a weapons inspection trip on the Black Sea. He also was frequently called as an expert witness on patent cases.

In 1999, Grodzins founded the nonprofit Cornerstones in Science, a public library initiative to improve public engagement with science. Based originally at the Curtis Memorial Library in Brunswick, Maine, Cornerstones now partners with libraries in Maine, Arizona, Texas, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and California. Among their initiatives was one that has helped supply telescopes to libraries and astronomy clubs around the country.

“He had a strong sense of wanting to do good for mankind,” says Steadman.

Awards

Grodzins authored more than 170 technical papers and holds more than 60 U.S. patents. His numerous accolades included being named a Guggenheim Fellow in 1964 and 1971, and a senior von Humboldt fellow in 1980. He was a fellow of the American Physical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and received an honorary doctor of science degree from Purdue University in 1998.

In 2021, the Denver X-Ray Conference gave Grodzins the Birks Award in X-Florescence Spectrometry, for having introduced “a handheld XRF unit which expanded analysis to in-field applications such as environmental studies, archeological exploration, mining, and more.”

Personal life

One evening in 1955, shortly after starting his work at Brookhaven, Grodzins decided to take a walk and explore the BNL campus. He found just one building that had lights on and was open, so he went in. Inside, a group was rehearsing a play. He was immediately smitten with one of the actors, Lulu Anderson, a young biologist. “I joined the acting company, and a year-and-a-half later, Lulu and I were married,” Grodzins had recalled. They were happily married for 62 years, until Lulu’s death in 2019.

They raised two sons, Dean, now of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Hal Grodzins, who lives in Maitland, Florida. Lee and Lulu owned a succession of beloved huskies, most of them named after physicists.

After living in Arlington, Massachusetts, the Grodzins family moved to Lexington, Massachusetts, in 1972 and bought a second home a few years later in Brunswick, Maine. Starting around 1990, Lee and Lulu spent every weekend, year-round, in Brunswick. In both places, they were avid supporters of their local libraries, museums, theaters, symphonies, botanical gardens, public radio, and TV stations.

Grodzins took his family along to conferences, fellowships, and other invitations. They all lived in Denmark for two sabbaticals, in 1964-65 and 1971-72, while Lee worked at the Neils Bohr Institute. They also traveled together to China for a month in 1975, and for two months in 1980. As part of the latter trip, they were among the first American visitors to Tibet since the 1940s. Lee and Lulu also traveled the world, from Antarctica to the Galapagos Islands to Greece.

His homes had basement workshops well-stocked with tools. His sons enjoyed a playroom he built for them in their Arlington home. He also once constructed his own high-fidelity record player, patched his old Volvo with fiberglass, changed his own oil, and put on the winter tires and chains himself. He was an early adopter of the home computer.

“His work in science and technology was part of a general love of gadgets and of fixing and making things,” his son, Dean, wrote in a Facebook post.

Lee is survived by Dean, his wife, Nora Nykiel Grodzins, and their daughter, Lily; and by Hal and his wife Cathy Salmons.

A remembrance and celebration for Lee Grodzins is planned for this summer. Donations in his name may be made to Cornerstones of Science.