MIT physicists have created a new ultrathin, two-dimensional material with unusual magnetic properties that initially surprised the researchers before they went on to solve the complicated puzzle behind those properties’ emergence. As a result, the work introduces a new platform for studying how materials behave at the most fundamental level — the world of quantum physics.

Ultrathin materials made of a single layer of atoms have riveted scientists’ attention since the discovery of the first such material — graphene, composed of carbon — about 20 years ago. Among other advances since then, researchers have found that stacking individual sheets of the 2D materials, and sometimes twisting them at a slight angle to each other, can give them new properties, from superconductivity to magnetism. Enter the field of twistronics, which was pioneered at MIT by Pablo Jarillo-Herrero, the Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Physics at MIT.

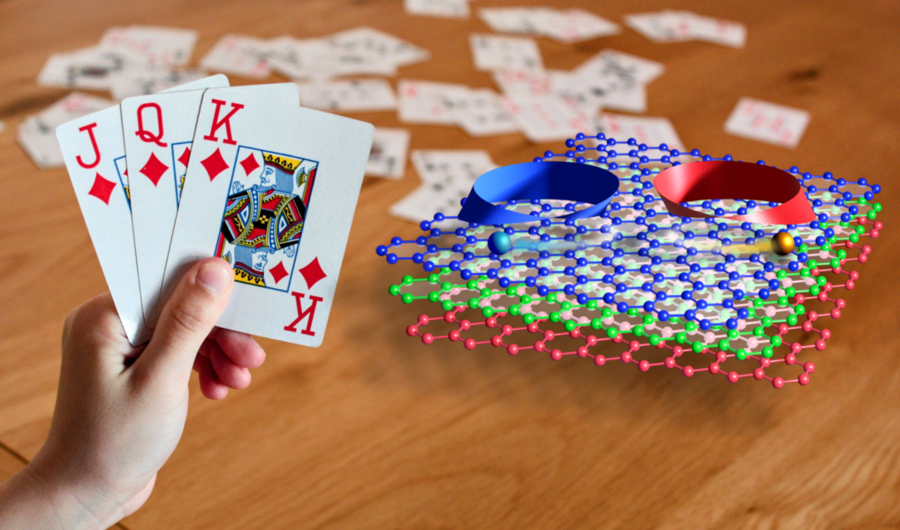

In the current research, reported in the Jan. 7 issue of Nature Physics, the scientists, led by Jarillo-Herrero, worked with three layers of graphene. Each layer was twisted on top of the next at the same angle, creating a helical structure akin to the DNA helix or a hand of three cards that are fanned apart.

“Helicity is a fundamental concept in science, from basic physics to chemistry and molecular biology. With 2D materials, one can create special helical structures, with novel properties which we are just beginning to understand. This work represents a new twist in the field of twistronics, and the community is very excited to see what else we can discover using this helical materials platform!” says Jarillo-Herrero, who is also affiliated with MIT’s Materials Research Laboratory.

Do the twist

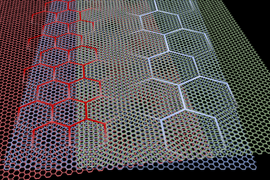

Twistronics can lead to new properties in ultrathin materials because arranging sheets of 2D materials in this way results in a unique pattern called a moiré lattice. And a moiré pattern, in turn, has an impact on the behavior of electrons.

“It changes the spectrum of energy levels available to the electrons and can provide the conditions for interesting phenomena to arise,” says Sergio C. de la Barrera, one of three co-first authors of the recent paper. De la Barrera, who conducted the work while a postdoc at MIT, is now an assistant professor at the University of Toronto.

In the current work, the helical structure created by the three graphene layers forms two moiré lattices. One is created by the first two overlapping sheets; the other is formed between the second and third sheets.

The two moiré patterns together form a third moiré, a supermoiré, or “moiré of a moiré,” says Li-Qiao Xia, a graduate student in MIT physics and another of the three co-first authors of the Nature Physics paper. “It’s like a moiré hierarchy.” While the first two moiré patterns are only nanometers, or billionths of a meter, in scale, the supermoiré appears at a scale of hundreds of nanometers superimposed over the other two. You can only see it if you zoom out to get a much wider view of the system.

A major surprise

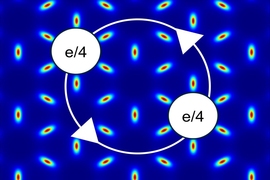

The physicists expected to observe signatures of this moiré hierarchy. They got a huge surprise, however, when they applied and varied a magnetic field. The system responded with an experimental signature for magnetism, one that arises from the motion of electrons. In fact, this orbital magnetism persisted to -263 degrees Celsius — the highest temperature reported in carbon-based materials to date.

But that magnetism can only occur in a system that lacks a specific symmetry — one that the team’s new material should have had. “So the fact that we saw this was very puzzling. We didn’t really understand what was going on,” says Aviram Uri, an MIT Pappalardo postdoc in physics and the third co-first author of the new paper.

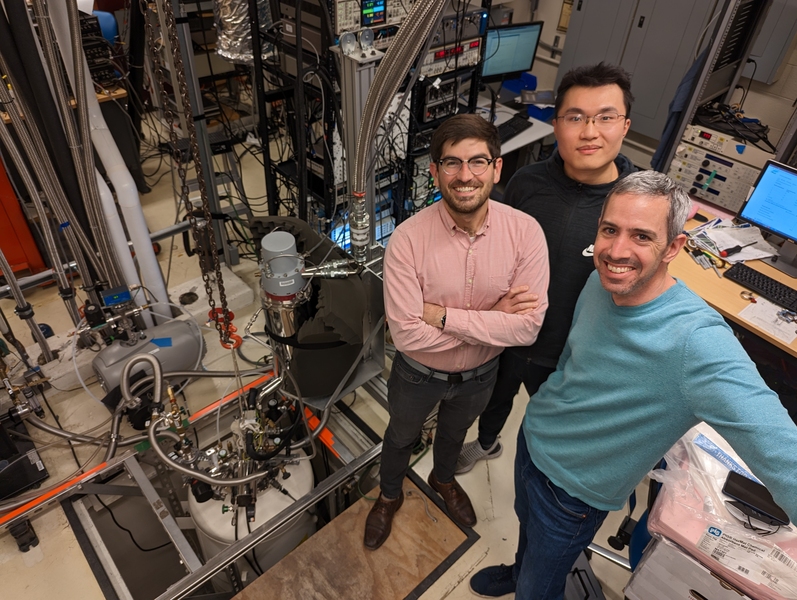

Other authors of the paper include MIT professor of physics Liang Fu; Aaron Sharpe of Sandia National Laboratories; Yves H. Kwan of Princeton University; Ziyan Zhu, David Goldhaber-Gordon, and Trithep Devakul of Stanford University; and Kenji Watanabe and Takashi Taniguchi of the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan.

What was happening?

It turns out that the new system did indeed break the symmetry that prohibits the orbital magnetism the team observed, but in a very unusual way. “What happens is that the atoms in this system aren’t very comfortable, so they move in a subtle orchestrated way that we call lattice relaxation,” says Xia. And the new structure formed by that relaxation does indeed break the symmetry locally, on the moiré length scale.

This opens the possibility for the orbital magnetism the team observed. However, if you zoom out to view the system on the supermoiré scale, the symmetry is restored. “The moiré hierarchy turns out to support interesting phenomena at different length scales,” says de la Barrera.

Concludes Uri: “It’s a lot of fun when you solve a riddle and it’s such an elegant solution. We’ve gained new insights into how electrons behave in these complex systems, insights that we couldn’t have had unless our experimental observations forced to think about these things.”

This work was supported by the Army Research Office, the National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Ross M. Brown Family Foundation, an MIT Pappalardo Fellowship, the VATAT Outstanding Postdoctoral Fellowship in Quantum Science and Technology, the JSPS KAKENHI, and a Stanford Science Fellowship. This work was carried out, in part, through the use of MIT.nano facilities.