Fusion energy has the potential to enable the energy transition from fossil fuels, enhance domestic energy security, and power artificial intelligence. Private companies have already invested more than $8 billion to develop commercial fusion and seize the opportunities it offers. An urgent challenge, however, is the discovery and evaluation of cost-effective materials that can withstand extreme conditions for extended periods, including 150-million-degree plasmas and intense particle bombardment.

To meet this challenge, MIT’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center (PSFC) has launched the Schmidt Laboratory for Materials in Nuclear Technologies, or LMNT (pronounced “element”). Backed by a philanthropic consortium led by Eric and Wendy Schmidt, LMNT is designed to speed up the discovery and selection of materials for a variety of fusion power plant components.

By drawing on MIT's expertise in fusion and materials science, repurposing existing research infrastructure, and tapping into its close collaborations with leading private fusion companies, the PSFC aims to drive rapid progress in the materials that are necessary for commercializing fusion energy on rapid timescales. LMNT will also help develop and assess materials for nuclear power plants, next-generation particle physics experiments, and other science and industry applications.

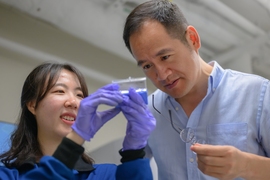

Zachary Hartwig, head of LMNT and an associate professor in the Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering (NSE), says, “We need technologies today that will rapidly develop and test materials to support the commercialization of fusion energy. LMNT’s mission includes discovery science but seeks to go further, ultimately helping select the materials that will be used to build fusion power plants in the coming years.”

A different approach to fusion materials

For decades, researchers have worked to understand how materials behave under fusion conditions using methods like exposing test specimens to low-energy particle beams, or placing them in the core of nuclear fission reactors. These approaches, however, have significant limitations. Low-energy particle beams only irradiate the thinnest surface layer of materials, while fission reactor irradiation doesn’t accurately replicate the mechanism by which fusion damages materials. Fission irradiation is also an expensive, multiyear process that requires specialized facilities.

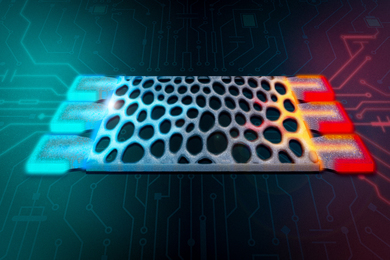

To overcome these obstacles, researchers at MIT and peer institutions are exploring the use of energetic beams of protons to simulate the damage materials undergo in fusion environments. Proton beams can be tuned to match the damage expected in fusion power plants, and protons penetrate deep enough into test samples to provide insights into how exposure can affect structural integrity. They also offer the advantage of speed: first, intense proton beams can rapidly damage dozens of material samples at once, allowing researchers to test them in days, rather than years. Second, high-energy proton beams can be generated with a type of particle accelerator known as a cyclotron commonly used in the health-care industry. As a result, LMNT will be built around a cost-effective, off-the-shelf cyclotron that is easy to obtain and highly reliable.

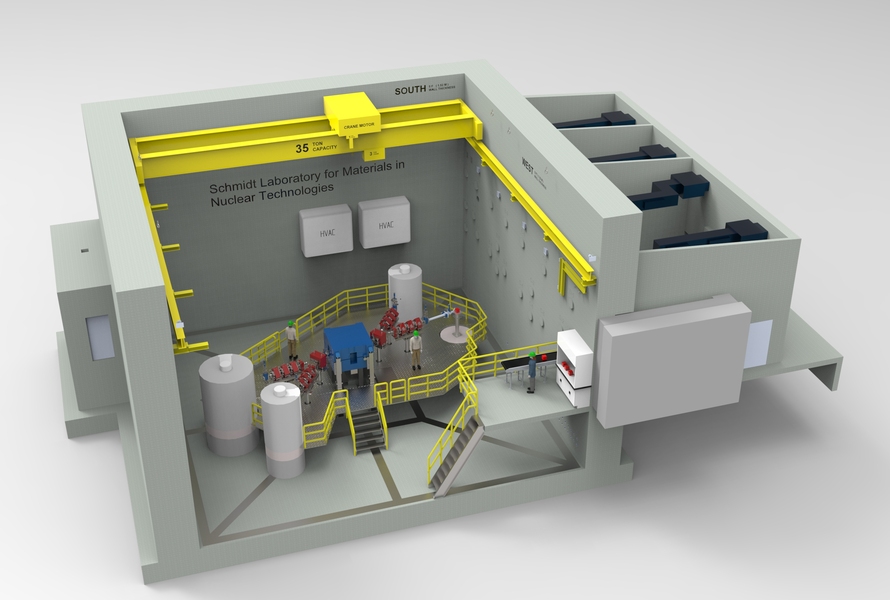

LMNT will surround its cyclotron with four experimental areas dedicated to materials science research. The lab is taking shape inside the large shielded concrete vault at PSFC that once housed the Alcator C-Mod tokamak, a record-setting fusion experiment that ran at the PSFC from 1992 to 2016. By repurposing C-Mod’s former space, the center is skipping the need for extensive, costly new construction and accelerating the research timeline significantly. The PSFC’s veteran team — who have led major projects like the Alcator tokamaks and advanced high-temperature superconducting magnet development — are overseeing the facilities design, construction, and operation, ensuring LMNT moves quickly from concept to reality. The PSFC expects to receive the cyclotron by the end of 2025, with experimental operations starting in early 2026.

“LMNT is the start of a new era of fusion research at MIT, one where we seek to tackle the most complex fusion technology challenges on timescales commensurate with the urgency of the problem we face: the energy transition,” says Nuno Loureiro, director of the PSFC, a professor of nuclear science and engineering, and the Herman Feshbach Professor of Physics. “It’s ambitious, bold, and critical — and that’s exactly why we do it.”

“What’s exciting about this project is that it aligns the resources we have today — substantial research infrastructure, off-the-shelf technologies, and MIT expertise — to address the key resource we lack in tackling climate change: time. Using the Schmidt Laboratory for Materials in Nuclear Technologies, MIT researchers advancing fusion energy, nuclear power, and other technologies critical to the future of energy will be able to act now and move fast,” says Elsa Olivetti, the Jerry McAfee Professor in Engineering and a mission director of MIT’s Climate Project.

In addition to advancing research, LMNT will provide a platform for educating and training students in the increasingly important areas of fusion technology. LMNT’s location on MIT’s main campus gives students the opportunity to lead research projects and help manage facility operations. It also continues the hands-on approach to education that has defined the PSFC, reinforcing that direct experience in large-scale research is the best approach to create fusion scientists and engineers for the expanding fusion industry workforce.

Benoit Forget, head of NSE and the Korea Electric Power Professor of Nuclear Engineering, notes, “This new laboratory will give nuclear science and engineering students access to a unique research capability that will help shape the future of both fusion and fission energy.”

Accelerating progress on big challenges

Philanthropic support has helped LMNT leverage existing infrastructure and expertise to move from concept to facility in just one-and-a-half years — a fast timeline for establishing a major research project.

“I’m just as excited about this research model as I am about the materials science. It shows how focused philanthropy and MIT’s strengths can come together to build something that’s transformational — a major new facility that helps researchers from the public and private sectors move fast on fusion materials,” emphasizes Hartwig.

By utilizing this approach, the PSFC is executing a major public-private partnership in fusion energy, realizing a research model that the U.S. fusion community has only recently started to explore, and demonstrating the crucial role that universities can play in the acceleration of the materials and technology required for fusion energy.

“Universities have long been at the forefront of tackling society’s biggest challenges, and the race to identify new forms of energy and address climate change demands bold, high-risk, high-reward approaches,” says Ian Waitz, MIT’s vice president for research. “LMNT is helping turn fusion energy from a long-term ambition into a near-term reality.”