Magnets and superconductors go together like oil and water — or so scientists have thought. But a new finding by MIT physicists is challenging this century-old assumption.

In a paper appearing today in the journal Nature, the physicists report that they have discovered a “chiral superconductor” — a material that conducts electricity without resistance, and also, paradoxically, is intrinsically magnetic. What’s more, they observed this exotic superconductivity in a surprisingly ordinary material: graphite, the primary material in pencil lead.

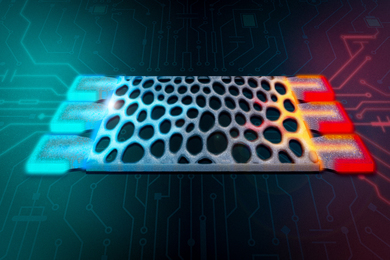

Graphite is made from many layers of graphene — atomically thin, lattice-like sheets of carbon atoms — that are stacked together and can easily flake off when pressure is applied, as when pressing down to write on a piece of paper. A single flake of graphite can contain several million sheets of graphene, which are normally stacked such that every other layer aligns. But every so often, graphite contains tiny pockets where graphene is stacked in a different pattern, resembling a staircase of offset layers.

The MIT team has found that when four or five sheets of graphene are stacked in this “rhombohedral” configuration, the resulting structure can exhibit exceptional electronic properties that are not seen in graphite as a whole.

In their new study, the physicists isolated microscopic flakes of rhombohedral graphene from graphite, and subjected the flakes to a battery of electrical tests. They found that when the flakes are cooled to 300 millikelvins (about -273 degrees Celsius), the material turns into a superconductor, meaning that any electrical current passing through the material can flow through without resistance.

They also found that when they swept an external magnetic field up and down, the flakes could be switched between two different superconducting states, just like a magnet. This suggests that the superconductor has some internal, intrinsic magnetism. Such switching behavior is absent in other superconductors.

“The general lore is that superconductors do not like magnetic fields,” says Long Ju, assistant professor of physics at MIT. “But we believe this is the first observation of a superconductor that behaves as a magnet with such direct and simple evidence. And that’s quite a bizarre thing because it is against people’s general impression on superconductivity and magnetism.”

Ju is senior author of the study, which includes MIT co-authors Tonghang Han, Zhengguang Lu, Zach Hadjri, Lihan Shi, Zhenghan Wu, Wei Xu, Yuxuan Yao, Jixiang Yang, Junseok Seo, Shenyong Ye, Muyang Zhou, and Liang Fu, along with collaborators from Florida State University, the University of Basel in Switzerland, and the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan.

Graphene twist

In everyday conductive materials, electrons flow through in a chaotic scramble, whizzing by each other, and pinging off the material’s atomic latticework. Each time an electron scatters off an atom, it has, in essence, met some resistance, and loses some energy as a result, normally in the form of heat. In contrast, when certain materials are cooled to ultracold temperatures, they can become superconducting, meaning that the material can allow electrons to pair up, in what physicists term “Cooper pairs.” Rather than scattering away, these electron pairs glide through a material without resistance. With a superconductor, then, no energy is lost in translation.

Since superconductivity was first observed in 1911, physicists have shown many times over that zero electrical resistance is a hallmark of a superconductor. Another defining property was first observed in 1933, when the physicist Walther Meissner discovered that a superconductor will expel an external magnetic field. This “Meissner effect” is due in part to a superconductor’s electron pairs, which collectively act to push away any magnetic field.

Physicists have assumed that all superconducting materials should exhibit both zero electrical resistance, and a natural magnetic repulsion. Indeed, these two properties are what could enable Maglev, or “magnetic levitation” trains, whereby a superconducting rail repels and therefore levitates a magnetized car.

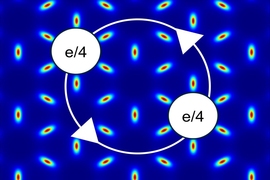

Ju and his colleagues had no reason to question this assumption as they carried out their experiments at MIT. In the last few years, the team has been exploring the electrical properties of pentalayer rhombohedral graphene. The researchers have observed surprising properties in the five-layer, staircase-like graphene structure, most recently that it enables electrons to split into fractions of themselves. This phenomenon occurs when the pentalayer structure is placed atop a sheet of hexagonal boron nitride (a material similar to graphene), and slightly offset by a specific angle, or twist.

Curious as to how electron fractions might change with changing conditions, the researchers followed up their initial discovery with similar tests, this time by misaligning the graphene and hexagonal boron nitride structures. To their surprise, they found that when they misaligned the two materials and sent an electrical current through, at temperatures less than 300 millikelvins, they measured zero resistance. It seemed that the phenomenon of electron fractions disappeared, and what emerged instead was superconductivity.

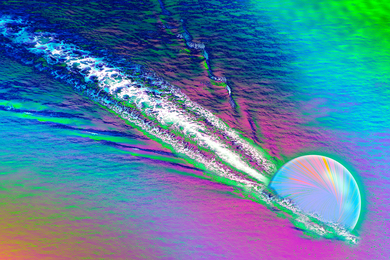

The researchers went a step further to see how this new superconducting state would respond to an external magnetic field. They applied a magnet to the material, along with a voltage, and measured the electrical current coming out of the material. As they dialed the magnetic field from negative to positive (similar to a north and south polarity) and back again, they observed that the material maintained its superconducting, zero-resistance state, except in two instances, once at either magnetic polarity. In these instances, the resistance briefly spiked, before switching back to zero, and returning to a superconducting state.

“If this were a conventional superconductor, it would just remain at zero resistance, until the magnetic field reaches a critical point, where superconductivity would be killed,” Zach Hadjri, a first-year student in the group, says. “Instead, this material seems to switch between two superconducting states, like a magnet that starts out pointing upward, and can flip downwards when you apply a magnetic field. So it looks like this is a superconductor that also acts like a magnet. Which doesn’t make any sense!”

“One of a kind”

As counterintuitive as the discovery may seem, the team observed the same phenomenon in six similar samples. They suspect that the unique configuration of rhombohedral graphene is the key. The material has a very simple arrangement of carbon atoms. When cooled to ultracold temperatures, the thermal fluctuation is minimized, allowing any electrons flowing through the material to slow down, sense each other, and interact.

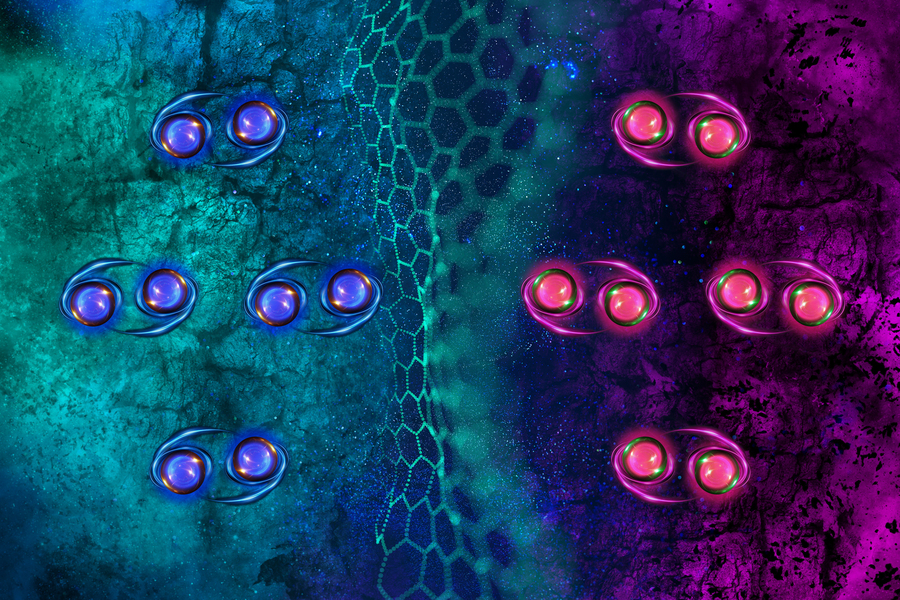

Such quantum interactions can lead electrons to pair up and superconduct. These interactions can also encourage electrons to coordinate. Namely, electrons can collectively occupy one of two opposite momentum states, or “valleys.” When all electrons are in one valley, they effectively spin in one direction, versus the opposite direction. In conventional superconductors, electrons can occupy either valley, and any pair of electrons is typically made from electrons of opposite valleys that cancel each other out. The pair overall then, has zero momentum, and does not spin.

In the team’s material structure, however, they suspect that all electrons interact such that they share the same valley, or momentum state. When electrons then pair up, the superconducting pair overall has a “non-zero” momentum, and spinning, that, along with many other pairs, can amount to an internal, superconducting magnetism.

“You can think of the two electrons in a pair spinning clockwise, or counterclockwise, which corresponds to a magnet pointing up, or down,” Tonghang Han, a fifth-year student in the group, explains. “So we think this is the first observation of a superconductor that behaves as a magnet due to the electrons’ orbital motion, which is known as a chiral superconductor. It’s one of a kind. It is also a candidate for a topological superconductor which could enable robust quantum computation.”

“Everything we’ve discovered in this material has been completely out of the blue,” says Zhengguang Lu, a former postdoc in the group and now an assistant professor at Florida State University. “But because this is a simple system, we think we have a good chance of understanding what is going on, and could demonstrate some very profound and deep physics principles.”

“It is truly remarkable that such an exotic chiral superconductor emerges from such simple ingredients,” adds Liang Fu, professor of physics at MIT. “Superconductivity in rhombodedral graphene will surely have a lot to offer.”

The part of the research carried out at MIT was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and a MathWorks Fellowship. This research was carried out, in part, using facilities at MIT.nano.