Treating severe or chronic injury to soft tissues such as skin and muscle is a challenge in health care. Current treatment methods can be costly and ineffective, and the frequency of chronic wounds in general from conditions such as diabetes and vascular disease, as well as an increasingly aging population, is only expected to rise.

One promising treatment method involves implanting biocompatible materials seeded with living cells (i.e., microtissue) into the wound. The materials provide a scaffolding for stem cells, or other precursor cells, to grow into the wounded tissue and aid in repair. However, current techniques to construct these scaffolding materials suffer a recurring setback. Human tissue moves and flexes in a unique way that traditional soft materials struggle to replicate, and if the scaffolds stretch, they can also stretch the embedded cells, often causing those cells to die. The dead cells hinder the healing process and can also trigger an inadvertent immune response in the body.

"The human body has this hierarchical structure that actually un-crimps or unfolds, rather than stretches," says Steve Gillmer, a researcher in MIT Lincoln Laboratory's Mechanical Engineering Group. "That's why if you stretch your own skin or muscles, your cells aren't dying. What's actually happening is your tissues are uncrimping a little bit before they stretch."

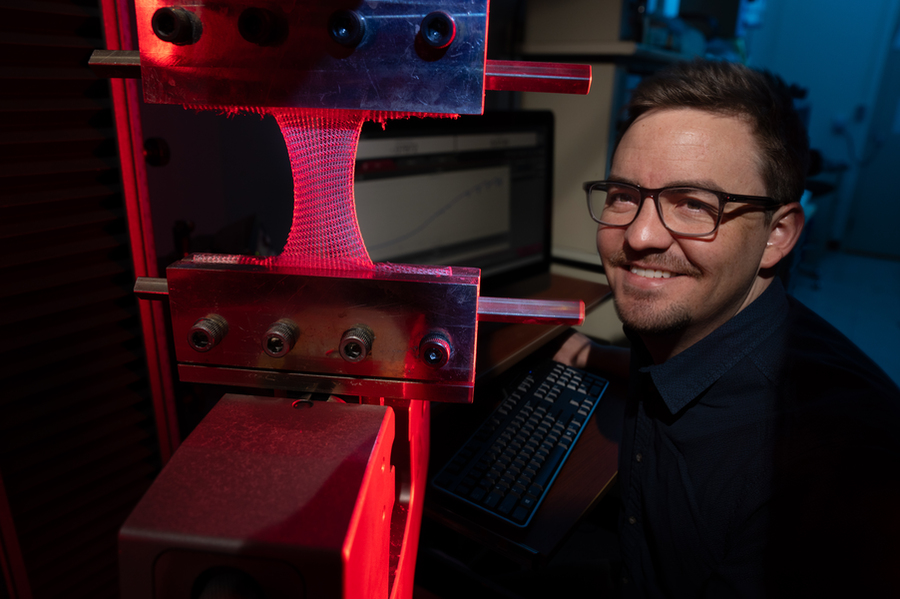

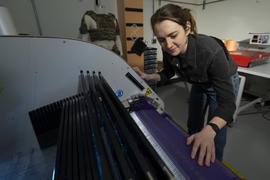

Gillmer is part of a multidisciplinary research team that is searching for a solution to this stretching setback. He is working with Professor Ming Guo from MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering and the laboratory's Defense Fabric Discovery Center (DFDC) to knit new kinds of fabrics that can uncrimp and move just as human tissue does.

The idea for the collaboration came while Gillmer and Guo were teaching a course at MIT. Guo had been researching how to grow stem cells on new forms of materials that could mimic the uncrimping of natural tissue. He chose electrospun nanofibers, which worked well, but were difficult to fabricate at long lengths, preventing him from integrating the fibers into larger knit structures for larger-scale tissue repair.

"Steve mentioned that Lincoln Laboratory had access to industrial knitting machines," Guo says. These machines allowed him to switch focus to designing larger knits, rather than individual yarns. "We immediately started to test new ideas through internal support from the laboratory."

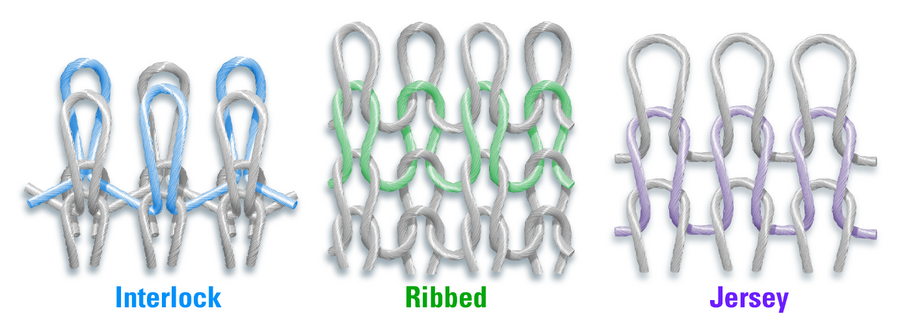

Gillmer and Guo worked with the DFDC to discover which knit patterns could move similarly to different types of soft tissue. They started with three basic knit constructions called interlock, rib, and jersey.

"For jersey, think of your T-shirt. When you stretch your shirt, the yarn loops are doing the stretching," says Emily Holtzman, a textile specialist at the DFDC. "The longer the loop length, the more stretch your fabric can accommodate. For ribbed, think of the cuff on your sweater. This fabric construction has a global stretch that allows the fabric to unfold like an accordion."

Interlock is similar to ribbed but is knitted in a denser pattern and contains twice as much yarn per inch of fabric. By having more yarn, there is more surface area on which to embed the cells. "Knit fabrics can also be designed to have specific porosities, or hydraulic permeability, created by the loops of the fabric and yarn sizes," says Erin Doran, another textile specialist on the team. "These pores can help with the healing process as well."

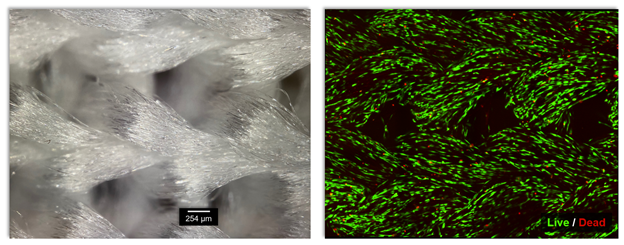

So far, the team has conducted a number of tests embedding mouse embryonic fibroblast cells and mesenchymal stem cells within the different knit patterns and seeing how they behave when the patterns are stretched. Each pattern had variations that affected how much the fabric could uncrimp, in addition to how stiff it became after it started stretching. All showed a high rate of cell survival, and in 2024 the team received an R&D 100 award for their knit designs.

Gillmer explains that although the project began with treating skin and muscle injuries in mind, their fabrics have the potential to mimic many different types of human soft tissue, such as cartilage or fat. The team recently filed a provisional patent that outlines how to create these patterns and identifies the appropriate materials that should be used to make the yarn. This information can be used as a toolbox to tune different knitted structures to match the mechanical properties of the injured tissue to which they are applied.

"This project has definitely been a learning experience for me," Gillmer says. "Each branch of this team has a unique expertise, and I think the project would be impossible without them all working together. Our collaboration as a whole enables us to expand the scope of the work to solve these larger, more complex problems."