As the saying goes, time is money. That’s certainly evident in the transportation sector, where people will pay more for direct flights, express trains, and other ways to get somewhere quickly.

Still, it is difficult to measure precisely how much people value their time. Now, a paper co-authored by an MIT economist uses ride-sharing data to reveal multiple implications of personalized pricing.

By focusing on a European ride-sharing platform that auctions its rides, the researchers found that people are more responsive to prices than to wait times. They also found that people pay more to save time during the workday, and that when people pay more to avoid waiting, it notably increases business revenues. And some segments of consumers are distinctly more willing than others to pay higher prices.

Specifically, when people can bid for rides that arrive sooner, the amount above the minimum price the platform can charge increases by 5.2 percent. Meanwhile, the gap between offered prices and the maximum that consumers are willing to pay decreases by 2.5 percent. In economics terms, this creates additional “surplus” value for firms, while lowering the “consumer surplus” in these transactions.

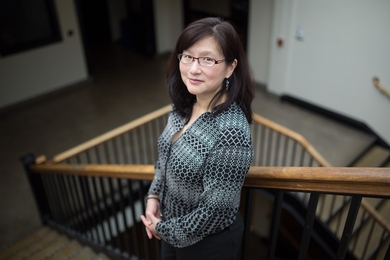

“One of the important quantities in transportation is the value of time,” says MIT economist Tobias Salz, co-author of a new paper detailing the study’s findings. “We came across a setting that offered a very clean way of examining this quantity, where the value of time is revealed by people’s transportation choices.”

The paper, “Personalized Pricing and the Value of Time: Evidence from Auctioned Cab Rides,” is being published in Econometrica. The authors are Nicholas Buchholz, an assistant professor of economics at Princeton University; Laura Doval, a professor at Columbia Business School; Jakub Kastl, a professor of economics at Princeton University; Filip Matejka, a professor at Charles University in Prague; and Salz, the Castle Krob Career Development Associate Professor of Economics in MIT’s Department of Economics.

It is not easy to study how much money people will spend to save time — and time alone. Transportation is one sector where it is possible to do so, though not the only one. People will also pay more for, say, an express pass to avoid long lines at an amusement park. But data for those scenarios, even when available, may contain complicating factors. (Also, the value of time shouldn’t be confused with how much people pay for services charged by the hour, from accountants to tuba lessons.)

In this case, however, the researchers were provided data from Liftago, a ride-sharing platform in Prague with a distinctive feature: It lets drivers bid on a passenger’s business, with the wait time until the auto arrives as one of the factors involved. Drivers can also indicate when they will be available. In studying how passengers compare offers with different wait times and prices, the researchers see exactly how much people are paying not to wait, other things being equal. All told, they examined 1.9 million ride requests and 5.2 million bids.

“It’s like an eBay for taxis,” Salz says. “Instead of assigning the driver to you, drivers bid for the passengers’ business. With this, we can very directly observe how people make their choices. How they value time is revealed by the wait and the prices attached to that. In many settings we don’t observe that directly, so it’s a very clean comparison that rids the data of a lot of confounds.”

The data set allows the researchers to examine many aspects of personalized pricing and the way it affects the transportation market in this setting. That produces a set of insights on its own, along with the findings on time valuation.

Ultimately, the researchers found that the elasticity of prices — how much they change — ranged from four to 10 times as much as the elasticity of wait times, meaning people are more keen on avoiding high prices.

The team found the overall value of time in this context is $13.21 per hour for users of the ride-share platform, though the researchers note that is not a universal measure of the value of time and is dependent on this setting. The study also shows that bids increase during work hours.

Additionally, the research reveals a split among consumers: The top quartile of bids placed a value on time that is 3.5 times higher than the value of the bids in the bottom quartile.

Then there is still the question of how much personalized pricing benefits consumers, providers, or both. The numbers, again, show that the overall surplus increases — meaning business benefits — while the consumer surplus is reduced. However, the data show an even more nuanced picture. Because the top quartile of bidders are paying substantially more to avoid longer waits, they are the ones who absorb the brunt of the costs in this kind of system.

“The majority of consumers still benefit,” Salz says. “The consumers hurt by this have a very high willingness to pay. The source of welfare gains is that most consumers can be brought into the market. But the flip side is that the firm, by knowing every consumer’s choke point, can extract the surplus. Welfare goes up, the ride-sharing platform captures most of that, and drivers — interestingly — also benefit from the system, although they do not have access to the data.”

Economic theory and other transportation studies alone would not necessarily have predicted the study’s results and various nuances.

“It was not clear a priori whether consumers benefit,” Salz observes. “That is not something you would know without going to the data.”

While this study might hold particular interest for firms and others interested in transportation, mobility, and ride-sharing, it also fits into a larger body of economics research about information in markets and how its presence, or absence, influences consumer behavior, consumer welfare, and the functioning of markets.

“The [research] umbrella here is really information about where to find trading partners and what their willingness to pay is,” Salz says. “What I’m broadly interested in is these types of information frictions and how they determine market outcomes, how they might impact consumers, and be used by firms.”

The research was supported, in part, by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the U.S. Department of Transportation, and the National Science Foundation.