Audio

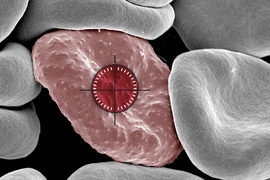

One of the newest weapons that scientists have developed against cancer is a type of engineered immune cell known as CAR-NK (natural killer) cells. Similar to CAR-T cells, these cells can be programmed to attack cancer cells.

MIT and Harvard Medical School researchers have now come up with a new way to engineer CAR-NK cells that makes them much less likely to be rejected by the patient’s immune system, which is a common drawback of this type of treatment.

The new advance may also make it easier to develop “off-the-shelf” CAR-NK cells that could be given to patients as soon as they are diagnosed. Traditional approaches to engineering CAR-NK or CAR-T cells usually take several weeks.

“This enables us to do one-step engineering of CAR-NK cells that can avoid rejection by host T cells and other immune cells. And, they kill cancer cells better and they’re safer,” says Jianzhu Chen, an MIT professor of biology, a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research,and one of the senior authors of the study.

In a study of mice with humanized immune systems, the researchers showed that these CAR-NK cells could destroy most cancer cells while evading the host immune system.

Rizwan Romee, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, is also a senior author of the paper, which appears today in Nature Communications. The paper’s lead author is Fuguo Liu, a postdoc at the Koch Institute and a research fellow at Dana-Farber.

Evading the immune system

NK cells are a critical part of the body’s natural immune defenses, and their primary responsibility is to locate and kill cancer cells and virus-infected cells. One of their cell-killing strategies, also used by T cells, is a process called degranulation. Through this process, immune cells release a protein called perforin, which can poke holes in another cell to induce cell death.

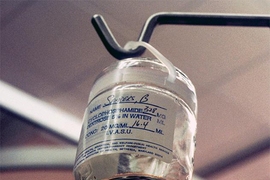

To create CAR-NK cells to treat cancer patients, doctors first take a blood sample from the patient. NK cells are isolated from the sample and engineered to express a protein called a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), which can be designed to target specific proteins found on cancer cells.

Then, the cells spend several weeks proliferating until there are enough to transfuse back into the patient. A similar approach is also used to create CAR-T cells. Several CAR-T cell therapies have been approved to treat blood cancers such as lymphoma and leukemia, but CAR-NK treatments are still in clinical trials.

Because it takes so long to grow a population of engineered cells that can be infused into the patient, and those cells may not be as viable as cells that came from a healthy person, researchers are exploring an alternative approach: using NK cells from a healthy donor.

Such cells could be grown in large quantities and would be ready whenever they were needed. However, the drawback to these cells is that the recipient’s immune system may see them as foreign and attack them before they can start killing cancer cells.

In the new study, the MIT team set out to find a way to help NK cells “hide” from a patient’s immune system. Through studies of immune cell interactions, they showed that NK cells could evade a host T-cell response if they did not carry surface proteins called HLA class 1 proteins. These proteins, usually expressed on NK cell surfaces, can trigger T cells to attack if the immune system doesn’t recognize them as “self.”

To take advantage of this, the researchers engineered the cells to express a sequence of siRNA (short interfering RNA) that interferes with the genes for HLA class 1. They also delivered the CAR gene, as well as the gene for either PD-L1 or single-chain HLA-E (SCE). PD-L1 and SCE are proteins that make NK cells more effective by turning up genes that are involved in killing cancer cells.

All of these genes can be carried on a single piece of DNA, known as a construct, making it simple to transform donor NK cells into immune-evasive CAR-NK cells. The researchers used this construct to create CAR-NK cells targeting a protein called CD-19, which is often found on cancerous B cells in lymphoma patients.

NK cells unleashed

The researchers tested these CAR-NK cells in mice with a human-like immune system. These mice were also injected with lymphoma cells.

Mice that received CAR-NK cells with the new construct maintained the NK cell population for at least three weeks, and the NK cells were able to nearly eliminate cancer in those mice. In mice that received either NK cells with no genetic modifications or NK cells with only the CAR gene, the host immune cells attacked the donor NK cells. In these mice, the NK cells died out within two weeks, and the cancer spread unchecked.

The researchers also found that these engineered CAR-NK cells were much less likely to induce cytokine release syndrome — a common side effect of immunotherapy treatments, which can cause life-threatening complications.

Because of CAR-NK cells’ potentially better safety profile, Chen anticipates that they could eventually be used in place of CAR-T cells. For any CAR-NK cells that are now in development to target lymphoma or other types of cancer, it should be possible to adapt them by adding the construct developed in this study, he says.

The researchers now hope to run a clinical trial of this approach, working with colleagues at Dana-Farber. They are also working with a local biotech company to test CAR-NK cells to treat lupus, an autoimmune disorder that causes the immune system to attack healthy tissues and organs.

The research was funded, in part, by Skyline Therapeutics, the Koch Institute Frontier Research Program through the Kathy and Curt Marble Cancer Research Fund and the Elisa Rah (2004, 2006) Memorial Fund, the Claudia Adams Barr Foundation, and the Koch Institute Support (core) Grant from the National Cancer Institute.