Quantum computers have the potential to solve complex problems that would be impossible for the most powerful classical supercomputer to crack.

Just like a classical computer has separate, yet interconnected, components that must work together, such as a memory chip and a CPU on a motherboard, a quantum computer will need to communicate quantum information between multiple processors.

Current architectures used to interconnect superconducting quantum processors are “point-to-point” in connectivity, meaning they require a series of transfers between network nodes, with compounding error rates.

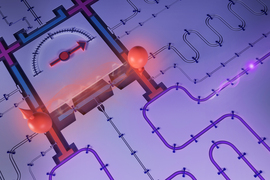

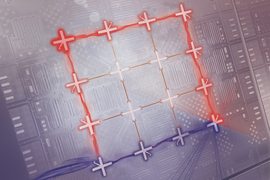

On the way to overcoming these challenges, MIT researchers developed a new interconnect device that can support scalable, “all-to-all” communication, such that all superconducting quantum processors in a network can communication directly with each other.

They created a network of two quantum processors and used their interconnect to send microwave photons back and forth on demand in a user-defined direction. Photons are particles of light that can carry quantum information.

The device includes a superconducting wire, or waveguide, that shuttles photons between processors and can be routed as far as needed. The researchers can couple any number of modules to it, efficiently transmitting information between a scalable network of processors.

They used this interconnect to demonstrate remote entanglement, a type of correlation between quantum processors that are not physically connected. Remote entanglement is a key step toward developing a powerful, distributed network of many quantum processors.

“In the future, a quantum computer will probably need both local and nonlocal interconnects. Local interconnects are natural in arrays of superconducting qubits. Ours allows for more nonlocal connections. We can send photons at different frequencies, times, and in two propagation directions, which gives our network more flexibility and throughput,” says Aziza Almanakly, an electrical engineering and computer science graduate student in the Engineering Quantum Systems group of the Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE) and lead author of a paper on the interconnect.

Her co-authors include Beatriz Yankelevich, a graduate student in the EQuS Group; senior author William D. Oliver, the Henry Ellis Warren (1894) Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) and professor of Physics, director of the Center for Quantum Engineering, and associate director of RLE; and others at MIT and Lincoln Laboratory. The research appears today in Nature Physics.

A scalable architecture

The researchers previously developed a quantum computing module, which enabled them to send information-carrying microwave photons in either direction along a waveguide.

In the new work, they took that architecture a step further by connecting two modules to a waveguide in order to emit photons in a desired direction and then absorb them at the other end.

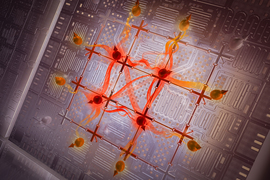

Each module is composed of four qubits, which serve as an interface between the waveguide carrying the photons and the larger quantum processors.

The qubits coupled to the waveguide emit and absorb photons, which are then transferred to nearby data qubits.

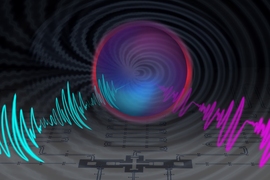

The researchers use a series of microwave pulses to add energy to a qubit, which then emits a photon. Carefully controlling the phase of those pulses enables a quantum interference effect that allows them to emit the photon in either direction along the waveguide. Reversing the pulses in time enables a qubit in another module any arbitrary distance away to absorb the photon.

“Pitching and catching photons enables us to create a ‘quantum interconnect’ between nonlocal quantum processors, and with quantum interconnects comes remote entanglement,” explains Oliver.

“Generating remote entanglement is a crucial step toward building a large-scale quantum processor from smaller-scale modules. Even after that photon is gone, we have a correlation between two distant, or ‘nonlocal,’ qubits. Remote entanglement allows us to take advantage of these correlations and perform parallel operations between two qubits, even though they are no longer connected and may be far apart,” Yankelevich explains.

However, transferring a photon between two modules is not enough to generate remote entanglement. The researchers need to prepare the qubits and the photon so the modules “share” the photon at the end of the protocol.

Generating entanglement

The team did this by halting the photon emission pulses halfway through their duration. In quantum mechanical terms, the photon is both retained and emitted. Classically, one can think that half-a-photon is retained and half is emitted.

Once the receiver module absorbs that “half-photon,” the two modules become entangled.

But as the photon travels, joints, wire bonds, and connections in the waveguide distort the photon and limit the absorption efficiency of the receiving module.

To generate remote entanglement with high enough fidelity, or accuracy, the researchers needed to maximize how often the photon is absorbed at the other end.

“The challenge in this work was shaping the photon appropriately so we could maximize the absorption efficiency,” Almanakly says.

They used a reinforcement learning algorithm to “predistort” the photon. The algorithm optimized the protocol pulses in order to shape the photon for maximal absorption efficiency.

When they implemented this optimized absorption protocol, they were able to show photon absorption efficiency greater than 60 percent.

This absorption efficiency is high enough to prove that the resulting state at the end of the protocol is entangled, a major milestone in this demonstration.

“We can use this architecture to create a network with all-to-all connectivity. This means we can have multiple modules, all along the same bus, and we can create remote entanglement among any pair of our choosing,” Yankelevich says.

In the future, they could improve the absorption efficiency by optimizing the path over which the photons propagate, perhaps by integrating modules in 3D instead of having a superconducting wire connecting separate microwave packages. They could also make the protocol faster so there are fewer chances for errors to accumulate.

“In principle, our remote entanglement generation protocol can also be expanded to other kinds of quantum computers and bigger quantum internet systems,” Almanakly says.

This work was funded, in part, by the U.S. Army Research Office, the AWS Center for Quantum Computing, and the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research.