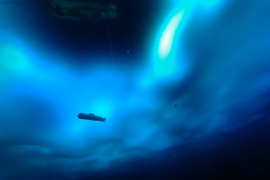

On June 18, 2023, the Titan submersible was about an hour-and-a-half into its two-hour descent to the Titanic wreckage at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean when it lost contact with its support ship. This cease in communication set off a frantic search for the tourist submersible and five passengers onboard, located about two miles below the ocean's surface.

Deep-ocean search and recovery is one of the many missions of military services like the U.S. Coast Guard Office of Search and Rescue and the U.S. Navy Supervisor of Salvage and Diving. For this mission, the longest delays come from transporting search-and-rescue equipment via ship to the area of interest and comprehensively surveying that area. A search operation on the scale of that for Titan — which was conducted 420 nautical miles from the nearest port and covered 13,000 square kilometers, an area roughly twice the size of Connecticut — could take weeks to complete. The search area for Titan is considered relatively small, focused on the immediate vicinity of the Titanic. When the area is less known, operations could take months. (A remotely operated underwater vehicle deployed by a Canadian vessel ended up finding the debris field of Titan on the seafloor, four days after the submersible had gone missing.)

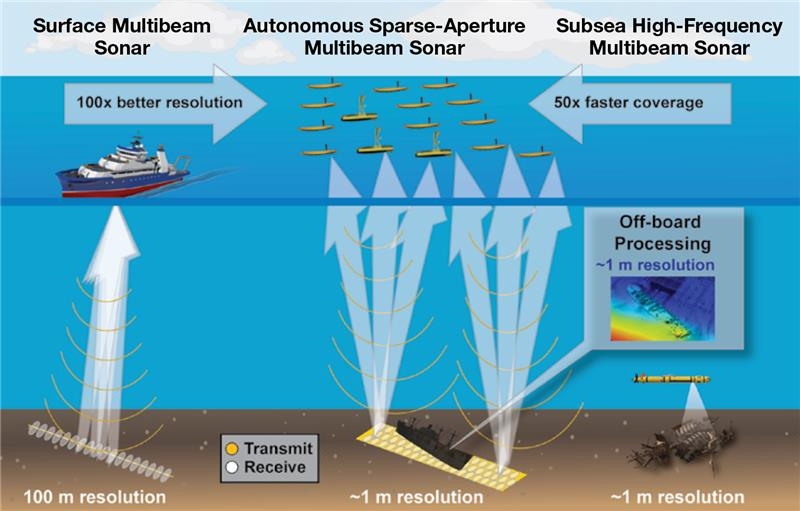

A research team from MIT Lincoln Laboratory and the MIT Department of Mechanical Engineering's Ocean Science and Engineering lab is developing a surface-based sonar system that could accelerate the timeline for small- and large-scale search operations to days. Called the Autonomous Sparse-Aperture Multibeam Echo Sounder, the system scans at surface-ship rates while providing sufficient resolution to find objects and features in the deep ocean, without the time and expense of deploying underwater vehicles. The echo sounder — which features a large sonar array using a small set of autonomous surface vehicles (ASVs) that can be deployed via aircraft into the ocean — holds the potential to map the seabed at 50 times the coverage rate of an underwater vehicle and 100 times the resolution of a surface vessel.

"Our array provides the best of both worlds: the high resolution of underwater vehicles and the high coverage rate of surface ships," says co–principal investigator Andrew March, assistant leader of the laboratory's Advanced Undersea Systems and Technology Group. "Though large surface-based sonar systems at low frequency have the potential to determine the materials and profiles of the seabed, they typically do so at the expense of resolution, particularly with increasing ocean depth. Our array can likely determine this information, too, but at significantly enhanced resolution in the deep ocean."

Underwater unknown

Oceans cover 71 percent of Earth's surface, yet more than 80 percent of this underwater realm remains undiscovered and unexplored. Humans know more about the surface of other planets and the moon than the bottom of our oceans. High-resolution seabed maps would not only be useful to find missing objects like ships or aircraft, but also to support a host of other scientific applications: understanding Earth's geology, improving forecasting of ocean currents and corresponding weather and climate impacts, uncovering archaeological sites, monitoring marine ecosystems and habitats, and identifying locations containing natural resources such as mineral and oil deposits.

Scientists and governments worldwide recognize the importance of creating a high-resolution global map of the seafloor; the problem is that no existing technology can achieve meter-scale resolution from the ocean surface. The average depth of our oceans is approximately 3,700 meters. However, today's technologies capable of finding human-made objects on the seabed or identifying person-sized natural features — these technologies include sonar, lidar, cameras, and gravitational field mapping — have a maximum range of less than 1,000 meters through water.

Ships with large sonar arrays mounted on their hull map the deep ocean by emitting low-frequency sound waves that bounce off the seafloor and return as echoes to the surface. Operation at low frequencies is necessary because water readily absorbs high-frequency sound waves, especially with increasing depth; however, such operation yields low-resolution images, with each image pixel representing a football field in size. Resolution is also restricted because sonar arrays installed on large mapping ships are already using all of the available hull space, thereby capping the sonar beam's aperture size. By contrast, sonars on autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that operate at higher frequencies within a few hundred meters of the seafloor generate maps with each pixel representing one square meter or less, resulting in 10,000 times more pixels in that same football field–sized area. However, this higher resolution comes with trade-offs: AUVs are time-consuming and expensive to deploy in the deep ocean, limiting the amount of seafloor that can be mapped; they have a maximum range of about 1,000 meters before their high-frequency sound gets absorbed; and they move at slow speeds to conserve power. The area-coverage rate of AUVs performing high-resolution mapping is about 8 square kilometers per hour; surface vessels map the deep ocean at more than 50 times that rate.

A solution surfaces

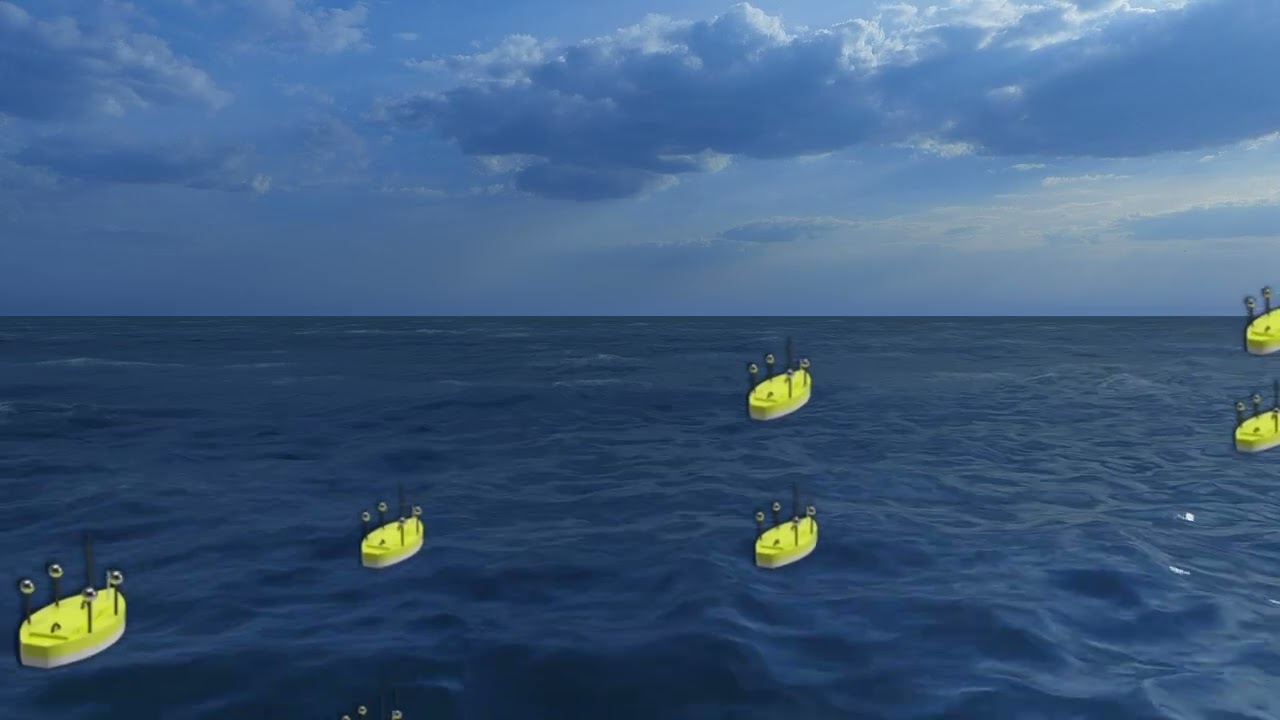

The Autonomous Sparse-Aperture Multibeam Echo Sounder could offer a cost-effective approach to high-resolution, rapid mapping of the deep seafloor from the ocean's surface. A collaborative fleet of about 20 ASVs, each hosting a small sonar array, effectively forms a single sonar array 100 times the size of a large sonar array installed on a ship. The large aperture achieved by the array (hundreds of meters) produces a narrow beam, which enables sound to be precisely steered to generate high-resolution maps at low frequency. Because very few sonars are installed relative to the array's overall size (i.e., a sparse aperture), the cost is tractable.

However, this collaborative and sparse setup introduces some operational challenges. First, for coherent 3D imaging, the relative position of each ASV's sonar subarray must be accurately tracked through dynamic ocean-induced motions. Second, because sonar elements are not placed directly next to each other without any gaps, the array suffers from a lower signal-to-noise ratio and is less able to reject noise coming from unintended or undesired directions. To mitigate these challenges, the team has been developing a low-cost precision-relative navigation system and leveraging acoustic signal processing tools and new ocean-field estimation algorithms. The MIT campus collaborators are developing algorithms for data processing and image formation, especially to estimate depth-integrated water-column parameters. These enabling technologies will help account for complex ocean physics, spanning physical properties like temperature, dynamic processes like currents and waves, and acoustic propagation factors like sound speed.

Processing for all required control and calculations could be completed either remotely or onboard the ASVs. For example, ASVs deployed from a ship or flying boat could be controlled and guided remotely from land via a satellite link or from a nearby support ship (with direct communications or a satellite link), and left to map the seabed for weeks or months at a time until maintenance is needed. Sonar-return health checks and coarse seabed mapping would be conducted on board, while full, high-resolution reconstruction of the seabed would require a supercomputing infrastructure on land or on a support ship.

"Deploying vehicles in an area and letting them map for extended periods of time without the need for a ship to return home to replenish supplies and rotate crews would significantly simplify logistics and operating costs," says co–principal investigator Paul Ryu, a researcher in the Advanced Undersea Systems and Technology Group.

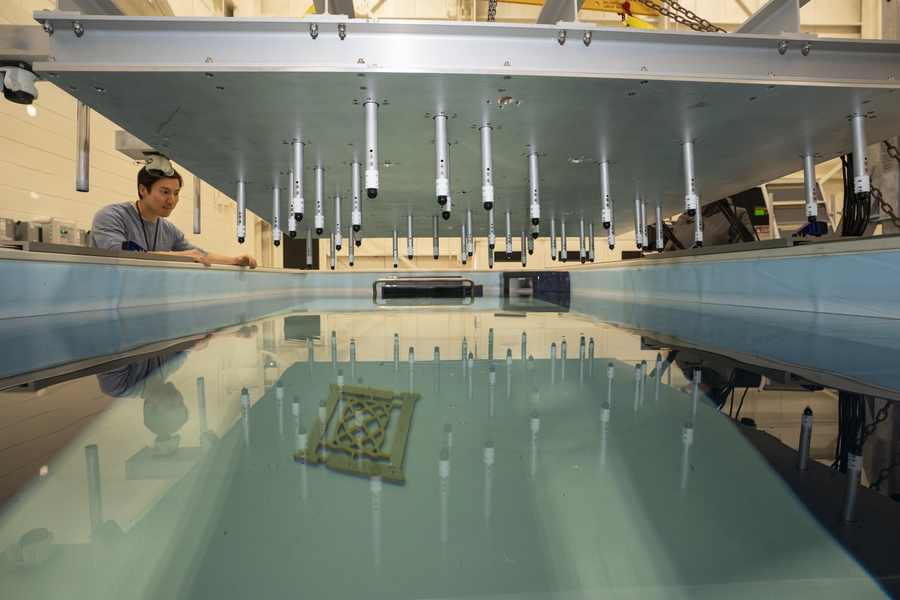

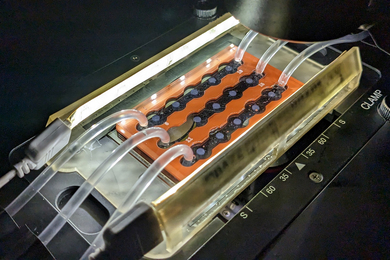

Since beginning their research in 2018, the team has turned their concept into a prototype. Initially, the scientists built a scale model of a sparse-aperture sonar array and tested it in a water tank at the laboratory's Autonomous Systems Development Facility. Then, they prototyped an ASV-sized sonar subarray and demonstrated its functionality in Gloucester, Massachusetts. In follow-on sea tests in Boston Harbor, they deployed an 8-meter array containing multiple subarrays equivalent to 25 ASVs locked together; with this array, they generated 3D reconstructions of the seafloor and a shipwreck. Most recently, the team fabricated, in collaboration with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, a first-generation, 12-foot-long, all-electric ASV prototype carrying a sonar array underneath. With this prototype, they conducted preliminary relative navigation testing in Woods Hole, Massachusetts and Newport, Rhode Island. Their full deep-ocean concept calls for approximately 20 such ASVs of a similar size, likely powered by wave or solar energy.

This work was funded through Lincoln Laboratory's internally administered R&D portfolio on autonomous systems. The team is now seeking external sponsorship to continue development of their ocean floor–mapping technology, which was recognized with a 2024 R&D 100 Award.